Olney Odyssey #21 LACAPS

By Peter Olney

In Olney Odyssey #20 I arrived in Los Angeles and found employment with the Los Angeles Coalition Against Plant Shutdowns, LACAPS, a labor/community coalition that really enabled me to enter the LA scene in very rapid fashion and gave me access to a lot of wonderful people, some of whom have become lifelong friends.

The offices of LACAPS were at the First Unitarian Universalist Church of Los Angeles off of Vermont, at Eighth Street. A very famous institution, this church. It previously had a pastor named Stephen Fritchman who during the Red Scare was a friend, confidant and supporter of many of the people being persecuted by Joseph McCarthy. Fritchman was subpoenaed twice to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, also known as HUAC, a body that eventually was closed down because of its abuses. My office was there, and this was nice for me because it was going home: I was raised in the Unitarian Universalist Church.

In 1981 General Motors worker Kathy Seal launched LACAPS alongside Al Belmontes and Gary Peoples from UAW Local 216 in South Gate California where their GM Assembly plant was under threat of closure. LACAPS was strengthened by a very successful conference in 1982 on factory shutdowns and runaways entitled: Western International Conference on Economic Dislocation. The principal conference organizer was an Episcopal Priest named Dick Gillett who became a family friend and later officiated at my marriage to Christina Perez in 1985. Goetz Wolff was his right hand man and served as the director of the conference.

The organizers of the 1982 conference constituted themselves as the Board of Directors of LACAPS. Kathy Seal was the staff organizer of LACAPS, and I was hired to work with her.

Similar coalitions of impacted labor unions and their community allies were being established all over the country to combat massive economic dislocation in basic manufacturing. The Bay Area Plant Closures project was the Northern California sister project to LACAPS.

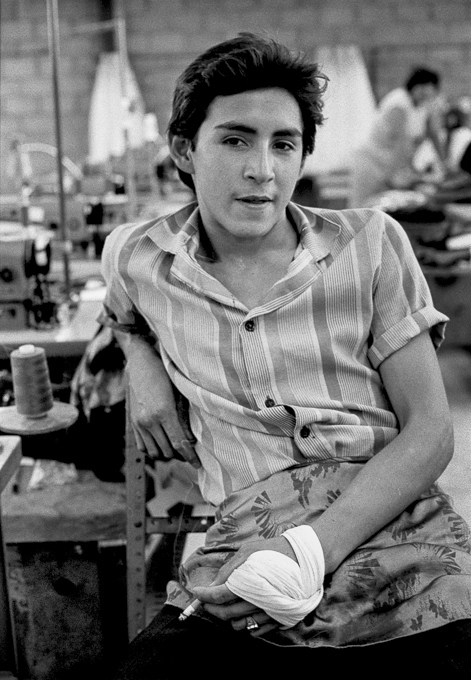

One of the partners in this Coalition Against Plant Shutdowns was the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU). Many people don’t know this, but LA was always the second center of garment production in the country after New York, and at the time I moved to Los Angeles there were about 100,000 garment workers in Los Angeles County. The union represented probably five or six thousand of them.

One of my first assignments was to go out and provide support for a strike at a company called Southern California Davis Pleating. It was a shop, as its name suggests, that supplied pleating services for fashion designers, interior designers, home dressmakers, fashion colleges, film companies, advertising, theatrical costumiers, and milliners.

I went out to their picket lines on 10th Street just east of downtown. And I vividly remember this picket line with about 150 women, mostly Mexican, carrying the red and black flags, “Banderas Rojinegras,” which in Mexico symbolize a strike. Red is the color of the international proletariat and black is the color honoring the martyrs in the fight for the eight hour day. I had never seen such banners before and I think they are a particular Mexican and Latin American tradition. This was another of many moments where I realized “I’m not in Boston anymore.”

The Davis Pleating strike lasted for seven months. It was triggered when the company demanded that its workers take a 20% wage cut, yield four paid holidays and two weeks’ vacation time per year, and give up cost-of-living raises and some medical benefits, as well as give up seniority rights and the right to reject overtime work. Ultimately the strike put the company out of business.

I remember going to the headquarters of the International Ladies Garment Workers in Los Angeles, which was on South Grand, and meeting the organizing director of the union, an amazing man named Miguel Machuca. He became a real mentor to me in terms of organizing and particularly in organizing Latino immigrants. He was from the State of Jalisco, Mexico. Miguel had crossed the border with the clothes on his back and had become a garment worker and a skilled cutter. From that position he successfully organized California Swimwear Co. in 1972. In 1982, one year before my arrival, he became the Western States organizing director of the union.

There were approximately eight to ten people working in the organizing department, all bilingual, and all Spanish speakers. In fact, the ILGWU was the first union in Los Angeles tohave a Latino organizing director and a staff that all spoke Spanish, many of whom were of Mexican descent. So, the ILGWU at that moment in history, in the early- to mid-Eighties played kind of a vanguard role in the labor movement because it was a union with the capacity to organize Spanish-speaking workers. Many other unions did not.

I had graduated from the University of Massachusetts in Boston with a degree in Spanish and had organized in many workplaces in the greater Boston area where the workforce was Puerto Rican or Dominican, or Cuban. Even though I had learned Spanish pretty well, I never really mastered it until I came to Los Angeles. Spanish became the language of all the work I did in Southern California.

The ILGWU was a very important seminal force for the revitalization of LA labor.

It’s interesting because one of the unions now that plays a major role in organizing is the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union (HERE). They have approximately 20,000 members in LA County. Their members are largely Spanish speaking. But at the time I came to LA, the head of that union did not speak Spanish and refused to allow translation at his membership meetings. This was mainly because he felt threatened by the possibility that these workers would know what was going on and would get rid of him. And that eventually happened. A very skilled organizer named Maria Elena Durazo, who had trained at the ILGWU with Machuca, ran against him and beat him later on in the 1980s. She’s now a State Senator in the California Legislature.

Working with the ILGWU was a wonderful experience. Miguel Machuca was a brilliant tactician. I remember after I won a union representation election, I went to him chagrined because I had mistakenly inflated the earnings of the owner of the newly organized garment shop. The inflated numbers were printed on leaflets distributed to the work force in advance of the election. I found out subsequently that there were two garment shop owners with the same name, and that I had gotten the wrong one. I was worried that the results of the election would be nullified by my false propaganda slandering the boss. Miguel assured me that that was not a danger and that, “Peter, look at the positive. You just acquired a new skill!!”

I also got to know the other organizers, some of whom have remained friends to this day. All of them had their own talents: translation, leading chants on the bullhorn, singing, providing logistical support for a strike kitchen, and all the various detailed tasks necessary to win a labor struggle. ILGWU Presente!

Through working at the LA Coalition Against Plant Shutdowns I got the opportunity to take my first trip to Mexico. I went as part of a delegation of Southern California unionists invited to Mexico to participate in a conference at the Centro de Estudios Económicos y Sociales del Tercer Mundo (Center for Economic and Social Studies of the Third World), founded by Luis Echevarria, the President of Mexico in the early Seventies. The Center was in the hills outside of Mexico City. I was invited to go to this conference to represent LACAPS.

I went to Mexico City with two very historic figures in Los Angeles’s labor movement – Bert Corona and Soledad “Chole” Alatorre.

They were the leaders of Hermandad Mexicana, the Mexican Brotherhood, a fabled organization that organized and represented Mexican workers. So I was on a delegation with them, and that was a real experience to meet these legendary labor organizers and community leaders.

Corona had gone to USC from his hometown of San Antonio, Texas, in 1936, on a basketball scholarship. He ended up working in a warehouse represented by the International Longshore and Warehouse Union Local 26 and later became the first Latino President of the local, which at the time had 12,000 members. Today there’s a San Fernando Valley middle school named in his honor.

Alatorre was born in Mexico and, after emigrating, went to work in the garment industry of Los Angeles, where she became a prominent organizer.

Later on Alatorre, Corona and other left wing labor activists and Mexican émigrés founded CASA (Centro de Accion Social Autonomo), which played a key role in fostering Latino labor organization nationwide. CASA’s alumni/ae association includes many of the best and brightest in the California and Chicago labor movements.

One moment I’ll never forget in that visit to the Echevarria Center was when we were walking on the cobblestones at the Centro. Luisa Gratz, who remains to this day the president of ILWU Local 26, was wearing stiletto heels. As we walked across the cobblestones she got stuck. She couldn’t move. So, I gallantly swept her up from out of the cobblestones.

At the conference I met two people – a man named Jorge Carrillo and a woman named Norma Iglesias. They were a couple, and they were university-based researchers at the University of Baja California Norte, based in Tijuana.

They became friends to me, and together we hatched the idea of publishing a cross- border newsletter called Puente, The Bridge, that would link the struggles of workers in Southern California with the struggles of workers in Northern Mexico – given that there were a lot of commonalities in terms of the workforce, language, culture, and corporations that were crossing the border and locating production in this “maquiladora” region.

A maquiladora is a factory in Mexico operated by a foreign company. Maquiladoras export the majority of the goods produced in Mexico to the USA. Through this program, a foreign company may import raw materials, components for assembly, and equipment necessary to produce its goods without paying the 16% value added tax on these imported materials and equipment. US corporations were taking advantage of these tax breaks from the Mexican government to produce goods to be imported into the United States. So, we established this newsletter and published several issues of it.

One thing I remember vividly – and I have a picture of this man speaking – is going to a meeting in Tijuana, an editorial meeting to publish an issue of Puente, and getting invited to a small conference room on top of a bar/restaurant. An older man was holding forth there, speaking in very dramatic terms. He spoke for two hours without notes. I asked somebody, “Who is that?” They said “Oh, that’s Valentin Campa.” I didn’t know who Valentin Campa was, but it turned out he was a legendary figure in the Mexican labor movement, a leader of the Mexican Communist Party who ran for the presidency of Mexico in 1976, and who also led a very famous long and bitter railroad strike in Mexico.

So, I got to hear him speak and I guess two hours in Mexico is long by some standards, though I’m told that Fidel Castro used to speak for eight hours without notes. But it was quite an impressive thing to see somebody hold forth like that, in a completely coherent way for two hours without looking at a single note.

On the board of LACAPS there was a man named Goetz Wolff, who was an academic researcher based at the Urban Planning School at UCLA. I remember in 1984, about a year into my assignment with LACAPS, he suggested to me, “You know Peter, you might benefit from studying at UCLA at our School of Urban Planning” (which was a very pro-labor program) “And maybe you’ll want to do a joint Urban Planning/Masters in Business Administration, an MBA.”

This intrigued me, and I thought “Well, I’m at kind of a moment in my life (I was 33 years old) where I wasn’t really sure where I was going, but I certainly could use additional skills.” So I thought, “I’ll take a shot at that.” I applied to this joint degree program in the Spring of 1984 and, to my surprise, got accepted to study for a Masters in Urban Planning and a Masters in Business.

In the fall of 1984 labor radical and proletarian fighter Peter Olney entered the Anderson School of Management at UCLA.

More to come in the next installment on that particular undertaking, which was interesting, exciting, and very useful. I called it studying behind enemy lines!

.

“Again, as in Olney Odyssey #20, I benefited from the able and professional editing of my friend Byron Laursen”

…

Thanks, Peter

Hey, you took the right path. Bravo for all cocernred.

Peter thanks so much for your many labor journeys (a few of them with me back at the origins of LACAPS)! And for reappearing! I am at The Hearthstone Retirement Community in Seattle along with my wife Anne and am in basically good health at 93. warmest good wishes for you and Cristina. Abrazos calurosos! Dick Gillett