A Housing Assistance Council report shines new light on rural America’s housing crisis

By Kristi Eaton

This piece originally appeared in Barn Raiser

Rural America has nearly 29 million homes, but experts say that’s not enough to house the roughly 46 million people who live there.

A recent report by the Housing Assistance Council, a nonprofit that supports affordable housing efforts throughout rural America, found that rural America is losing affordable housing at an alarming rate, fueling a growing housing crisis.

“There’s a lack of affordable housing stock nationally,” says Lance George, director of Research and Information at the Housing Assistance Council. “But it’s even further exacerbated in rural areas [because] there’s a dearth of good quality rental housing or even rental housing of any type in many rural communities.” Over 1.4 million homes fail to meet basic standards of shelter, safety or essential services like water, sanitation and electricity, according to the report.

The report also found that rural homeowners and renters are becoming increasingly cost-burdened, as housing prices continue to rise in rural communities.

Though housing tends to cost less in rural areas, the report found that over 5.6 million people, or about a quarter of rural households, pay more than 30% of their monthly income on housing costs, and less than half of rural homeowners own their houses outright. (The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development defines families who pay more than 30% of their income for housing as “cost-burdened.”)

One reason there’s less affordable housing stock in rural America is due to the rise of “vacation homes,” or homes unoccupied for seasonal or recreational use.

Approximately 6 million homes, or 20%, are unoccupied in rural America, lower than the nationwide average of 11%. According, to the report, about 53% of all vacant seasonal or recreational homes nationwide are in rural areas, which account for nearly half of all rural home vacancies.

Further complicating the picture is the fact that some rural areas have seen their populations rise, as the Covid-19 pandemic helped spur migration from urban to rural areas.”

‘In the Shadows’

Homelessness in rural America is also prevalent, although experts and housing advocates say it’s less visible compared to urban parts of the country.

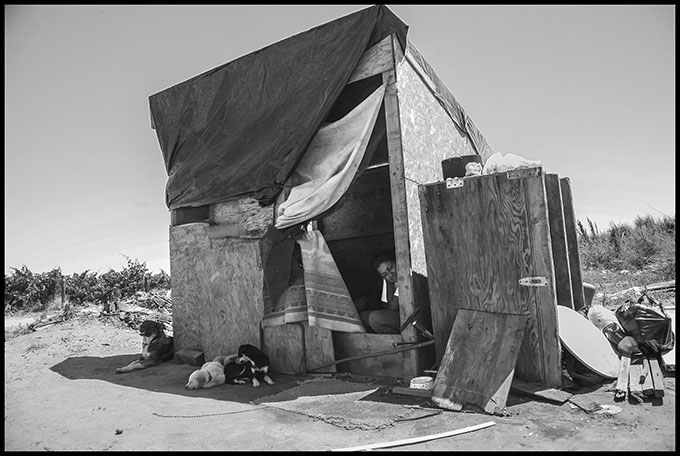

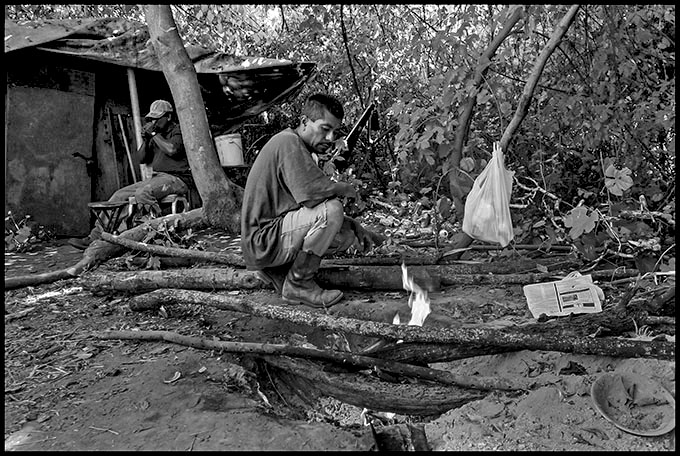

According to the report, “Rural homelessness may be simply less visible, as rural homeless people do not usually sleep in visible spaces, and emergency shelters may not exist in rural places.” Many rural people experiencing homelessness live in their cars or campers.

George says the homelessness population often go unnoticed in rural settings, especially those with precarious employment like farmworkers, who are more susceptible to homelessness.

“[Farmworkers are] a really overlooked group,” says George. “These are people who are working [in settings where] there’s no place to stay. So, they’re living [and] sleeping under trees or in their cars. And that is truly a homeless population. I think it’s really in the shadows.”

Farmworkers with employer-provided housing may not be better off. Recent investigations by ProPublica have revealed that immigrant dairy workers often live in substandard employer-provided housing, due to the fact that some state and federal laws exclude dairy farmworkers from housing protections. ProPublica found several farms in Wisconsin where workers lived in houses that had black mold covering the walls, crumbling ceilings, exposed electrical wiring and lacked functional toilets, appliances or heating systems.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development estimates that approximately 87,000 individuals, including 6,000 veterans, are currently homeless—about 19% of the total homeless population in the U.S. An estimated 58% of the rural homeless live in shelters.

Hsun-Ta Hsu is an associate professor of social work at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His research focuses on using big data tools and artificial intelligence to study homelessness and housing solutions.

Hsu said that poverty and a lack of affordable housing are the leading causes of homelessness in rural America. Other issues include a lack of access to mental healthcare resources and temporary housing or emergency shelters.

“It’s different in many ways compared to urban homelessness,” Hsu says. Rural people experiencing homelessness are “more likely to be unsheltered, and they’re more likely to be hidden. A lot of times, they’re doubling up [living with friends or family]—they’re couch surfing,” he says.

In 2023, Hsu received a grant from the National Alliance to End Homelessness to study rural homelessness in Missouri. As part of their research, Hsu’s team convenes what they call a “community action board” made up of community leaders, policymakers and people who have experienced homelessness to understand a community’s specific needs when it comes to addressing homelessness.

One promising avenue of Hsu’s research has been the Housing First approach. Housing First is a model that connects people with stable housing without preconditions, such as sobriety requirements, and then provides wraparound services to meet an individual’s needs. In recent years, it has also come under attack by conservatives. Sen. J.D. Vance, (R-Ohio) claimed at a Senate hearing last year, without evidence, that Housing First has a “social contagion effect” by normalizing bad behavior such as drug use, and Donald Trump has pledged to place homeless people in “tent cities.”

Despite the skeptics, Hsu is convinced about Housing First’s results. “To address rural homelessness, we know that the Housing First model works,” Hsu says. “So now the issue is the lack of affordable housing, [where] we have a bottleneck of people who are waiting a long period of time in order to get in the queue of supportive housing.”

Rural evictions are another hidden feature of the housing crisis. More than 200,000 rural families face an eviction each year, as rural renters face a lack of affordable rental housing and insufficient income with over half of rural renter households having an annual income of less than $35,000, a situation that particularly affects Black rural Americans. With few affordable rental options, rural evictions can become a fast track to homelessness.

Mobile Home Parks Face Rising Rents and Neglected Landlord Maintenance

Jaime Izaguirre is a community organizer for Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement. He works in rural areas across Iowa to address homelessness.

“I think there are three types of issues regarding housing in Iowa: cost, availability and quality,” he says. “The housing shortage is real in Iowa. There are not enough apartments or homes, especially for low- or extremely low-income families. The quality of housing stock in many places is under attack by corporate entities that see these homes as line-item investments on a spreadsheet. And in some cases, population and job growth is hard to sustain or encourage due to the lack of availability.”

He says one major issue in Iowa and across the country is mobile home investment groups that buy up trailer parks and hike rents while doing less than adequate maintenance and improvement practices.

“In some cases, these corporations are even using federal financing through Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae,” he said. “To our estimation there are at least 42 mobile home parks financed by those two enterprises in Iowa. We’re working with mobile home residents and associations across the state to help organize themselves and get much-needed repairs and improvements done in their parks.”

Izaguirre says housing is a mixture of policy, organizing and power.

“Why do we build housing? I believe the answer to that question should be as simple as because people need homes,” he says. “How we shape housing policy and planning shapes a city, a rural community, and the lives of the people living in said housing.”

…