Putting Members First: Ron Carey’s Lessons For Labor Movement Reform

By Rand Wilson and Steve Early

Books about union presidents are usually penned by professional writers — either academic historians, labor journalists, or paid flacks. Past accounts of the life and work of labor organization chiefs like John L. Lewis, Walter Reuther, Jimmy Hoffa, or Cesar Chavez have run the gamut from hagiographic to constructively critical. Few have had a biographer whose view of their leadership role is rooted in first-hand experience as a blue-collar worker in the same industry and union.

Ken Reiman’s personal connection to the subject matter of Ron Carey and the Teamsters (Monthly Review Press, 2024) resulted from his own career as a UPS driver and activist in the local union that Carey led before becoming president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters in the 1990s. Reiman’s insights into the workplace culture and organizational politics of IBT Local 804 in Queens, NY, before, during, and after Carey’s presidency provide a rank-and-file perspective on the challenges of institutional change in organized labor over the past fifty years.

“late 2023, newly-elected UAW leaders were conducting a major strike against U.S. automakers, after building a membership-based contract campaign of the sort never employed by the previous leadership during national bargaining.”

Carey’s story, as told by Reiman, contains many important lessons for younger union activists, whether they are Teamsters or involved in other unions. Organized labor today is in a state of very positive ferment. A reform movement in the United Auto Workers, modeled after Teamsters for a Democratic Union, has had similar success winning direct election of top officers and using that system oust old guard officials.

By late 2023, newly-elected UAW leaders were conducting a major strike against U.S. automakers, after building a membership-based contract campaign of the sort never employed by the previous leadership during national bargaining. Earlier in the year, new leadership in the Teamsters, elected in 2022 with TDU backing, engaged many of the union’s 330,000 members at UPS in a national contract fight that drew on the experience of the UPS strike in 1997, led by Ron Carey.

In California in 2023, workers in the state university system staged the largest higher education walk-out ever and union members at Kaiser Permanente conducted the biggest healthcare industry strike in U.S. labor history. Actors and writers participated in an overlapping work stoppage in Hollywood that involved more than 170,000 workers. Meanwhile, thousands of southern California hotel workers also struck for a new contract.

Workers at Starbucks’ have conducted what now appears to be a successful first contract campaign, after engaging in nationally coordinated protest activity and mini-strikes in particular workplaces. The landscape of labor organizing in Amazon warehouses and distribution centers is replete with similar shop-floor skirmishing between labor and management, including worker-led strikes over local issues in many locations with no formal bargaining rights or union recognition.

A similar dynamic mix of union democracy and reform struggles, at the local and national level, and heightened workplace militancy in many different sectors was, of course, the context for Ron Carey’s own late 20th century career as a union dissident, who became the first democratically elected president of what was, not long ago, the nation’s most corrupt and racketeer-dominated union.

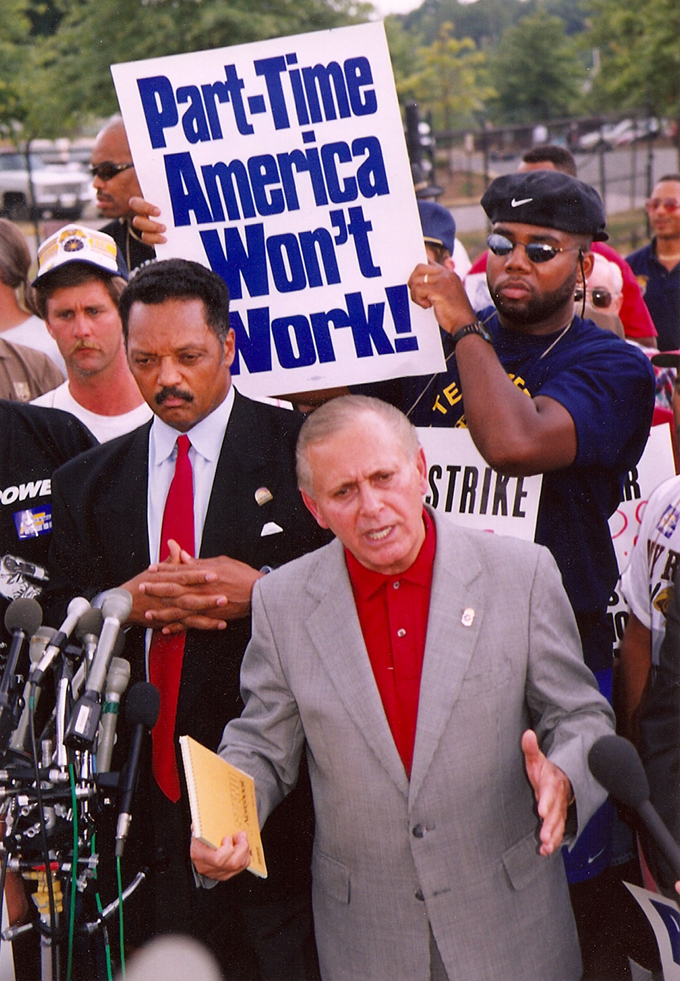

PHoto Earl’s second shot

Each phase of Carey’s rise and fall, as recounted in Putting Members First, is worthy of close study by those seeking to follow in his footsteps as a shop-floor militant, an opposition candidate for local union office, and a coalition-builder with other reformers. Finally, and most impressive, was Carey’s role as a national labor leader faced with the daunting challenge of transforming a dysfunctional organization, in the face of employer hostility and the internal resistance of union officials protecting their own perks, political power, and personal fiefdoms.

Below are some of the critical components of union revitalization, as recounted in this biography, that have continuing relevance to present-day reform struggles:

· Ousting local union incumbents.

Like many disgruntled members before and since, Carey first got involved in union politics because officials of Local 804, in the late 1950s, were so unresponsive to worker complaints and concerns. He ran for shop steward, beating a fellow driver who “didn’t want to rock the boat.” Rocking the boat became Carey’s “MO” for the rest of his career. But he understood the limitations of being a “Lone Ranger.” Reiman’s account of how Carey assembled a team of like-minded co-workers to take on the union establishment is a good primer for anyone trying to do that, at the local union level, today.

It took Carey a decade, and several election defeats running for lesser offices, before he became 804 president on a platform of cleaning up the local, enforcing the contract, and improving pensions. As he did 24 years later in the “Marble Palace” in Washington, Carey cut his own salary to show that he was serious about putting union resources to work for the membership.

· Using direct action on the job.

The year Ron Carey became a Teamster steward, Local 804 had twenty wildcat strikes; not long afterwards UPS drivers in NYC struck for six weeks, over the objections of local and national union officials. Throughout his three decades in the local, Carey tapped into, rather than tried to suppress, rank-and-file unrest that took form of job actions, whether legal or not.

When Carey became president in 1968, after campaigning for a year as part of an opposition slate, his first challenge was striking UPS again. This time, 804 members walked out for more than two months to win a first-ever “25-and-out-pension” provision with UPS, effectively using contract rejection votes at mass meetings to win a better final offer from management.

· Challenging bureaucratic control of bargaining.

As Reiman reports, Carey quickly developed a reputation for honesty, transparency, and independence from the corrupt regional and national power structure of the IBT. But, in the Teamsters then, and in many other unions today, islands of militancy have trouble surviving in a sea of business unionism. Putting Members First shows how dissident locals like Carey’s 804 must overcome attempts, by the union hierarchy, to undermine picket-line solidarity among workers bargaining with the same employer, but in different locals or national unions. Carey’s methods of thwarting management’s “divide-and-conquer” schemes, aided and abetted by top union officials, are worthy of emulation.

· Networking with like-minded reformers

In the 1980s, the IBT began negotiating more issues with UPS at the company-wide level – via a tightly controlled national bargaining committee – which reduced the scope and impact of local or regional bargaining. To counter this threat, Carey and Local 804 began to ally with UPS dissidents around the country, including those long active in TDU and equally opposed to a then-provision of the IBT constitution which required a two-thirds vote, rather than a simple majority, to reject any tentative agreement with an employer. Jousting with the International Union over imposition of unpopular UPS contracts—voted down by a majority of those covered by them—helped build the movement for democratizing the Teamsters, by linking bad bargaining outcomes to denial of membership rights.

· Winning and using One Member/One Vote

Most U.S. union members have no direct say about their national union officers and executive board members. The latter are elected by smaller groups of local union delegates at national conventions that tend to be leadership controlled, particularly when incumbents are up for re-election. These delegate bodies are resistant to changing national union constitutions to allow the more democratic method used in APWU, ILWU, the NewsGuild/CWA, and a few others.

The only major breakthroughs in direct voting on top officers have occurred, after corruption scandals and resulting judicial intervention involving the IBT, UAW, and LIUNA. Without a rank-and-file reform movement—of the type which backed Carey during his two Teamster presidential campaigns, or which developed recently in the UAW—it remains hard for opposition candidates to win any union-wide election. The lesson of this book is to be ready for that political opening when and if it occurs, while fighting for “one-member/one vote” in the meantime.

· Tackling internal restructuring

When Carey and other members of his reform slate took over Teamster headquarters in 1992, the “Marble Palace” was not just a monument to past Teamster extravagance. It was full of poorly performing departments, with overpaid and/or incompetent staffers hostile to the goals of the new administration. Foes of reform also controlled all the Teamster joint councils, area conferences, and the boards of the many health and welfare and pension benefit funds. These powerful officials wanted Carey and his team to fall on their faces.

Working with TDU activists around the country and a minority of reform-minded local officers, Carey put 75 troubled locals under trusteeship, cut waste, stepped up Teamster organizing, hired aggressive new staff and empowered members. As Reiman documents, the elimination of the “area conferences” was a major restructuring victory—and a blueprint worth following, as needed, in other unions saddled with unnecessary layers of bureaucracy and staff featherbedding.

· Staying close to the members

To his credit, Carey never felt comfortable in his new inside-the-Beltway world (where a sycophantic culture of political hustling and over-paid “consulting” would, in the end, contribute to his undoing.) He liked hanging out with working Teamsters in Queens, not politicians or other high-ranking union officials in Washington. He was a work horse, not a show horse, a hands-on handler of IBT members’ daily problems, large and small. His organizational accomplishments, as Reiman shows, were always rooted in a strong personal connection with the membership, that many elected and appointed officials seem to lose as they ascend through the ranks of their respective union bureaucracies.

· Taking on employers, with new allies

Carey’s finest hour came in 1997 when the presence of someone at the top of the union who sincerely believed in the power of the rank and file made it possible for 185,000 UPS workers to win the biggest nationwide strike in the last thirty years. The UPS contract campaign employed membership education and mobilization, labor-community coalition building, and outreach to UPS customers and the general public, via the media, that the union had never utilized before.

Two years before, the Teamsters, under Carey, had cast 1.4 million votes in the AFL-CIO’s first contested election in 100 years, thereby helping to secure the victory of a new leadership more helpful in labor-management showdowns like the UPS strike. The IBT joined Jobs with Justice, embraced single payer health care reform, and campaigned against free trade. The union ditched its traditional ties to conservative Republicans, while maintaining some—albeit not enough—distance from Democrats who disappointed or betrayed labor.

· Anticipating a counter-revolution

When union reformers win, they still face pushback from entrenched internal foes. Carey’s crackdown on crooks and leadership perks alienated large sections of the Teamster officialdom. Still-powerful bureaucrats who had split their support between two “Old Guard” candidates in 1991, bankrolled a unified $4 million challenge, fronted by James Hoffa, five years later. The wealthy Detroit labor lawyer masqueraded successfully as a populist critic of a “New Teamster” establishment that was spendthrift, incompetent, and run by “outsiders.”

As Reiman recounts, the Carey campaign fund-raising misconduct in 1996 was a self-inflicted blow to the moral authority and public reputation of his administration. It was the result of corner-cutting and top-down campaigning that was very different from the bottom up approach that propelled Carey to victory five years before. The moral of this story: if you’re going to take on union corruption and corporate America at the same time, don’t let opportunistic “outsiders,” hitch their wagon to your team. Their greed, bad judgement, and lack of any connection to union reform will lead to grifting of a new sort.

While the tragedy of Ron Carey’s criminal prosecution and eventual banning from the union makes for painful reading, Ken Reiman’s book reminds us that the Teamster reform movement survived ‘Donorgate’ in the mid-1990s and upheld his legacy of opposition to Teamster old guard politics and policies. The work of Carey and many like-minded supporters four decades ago raised the bar and set the stage for Teamster reformers to reclaim their national headquarters nearly 25 years later.

One result of that most recent national-level reform slate victory was the 2022-23 UPS contract campaign which drew on the lessons, experiences, and, in many cases, the leadership of 1997 strike veterans. In much media coverage and analysis of last year’s grassroots contract campaign and its results, Carey’s name, memory, and past strike role were often invoked.

To TDU members and the many other Teamsters whose votes made him the first directly elected national union president, Carey remains a heroic, not just tragic, figure. In a union where to this day, many local officers are wary of TDU, the pugnacious ex-Marine and former UPS-driver from Queens was a unique ally in a vibrant reform movement that has now spanned five decades. During that period, we had the privilege of working with Ron in different capacities and seeing him in action behind the scenes and in public, during several critical junctures in the union’s modern history.

We salute Brother Ken Reiman and Monthly Review Press for bringing Ron’s story to a new generation of labor activists faced with the unfinished task of revitalizing and reforming the U.S. labor movement. Reiman’s book will help ensure that Carey’s singular role will be remembered — and rightfully honored — long after his critics and detractors have been forgotten.

(In the late 1970s, Steve Early was an organizer, lawyer, and newspaper editor for the Professional Drivers Council (PROD), a Teamster reform group that became part of Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU). He assisted Ron Carey’s 1989-91 campaign for the Teamster presidency and, while on loan from the Communications Workers of America, served as a member of Carey’s headquarters transition team in early 1992. A longtime labor activist, Rand Wilson worked at Teamster headquarters in the union’s communications department, under Carey. He helped plan and implement the UPS contract campaign in 1997, and handled publicity for the subsequent two-week strike. In 2022-23, he worked as a TDU organizer aiding membership education and mobilization in support of the IBT’s latest UPS contract campaign.)

…

This piece has also run in Jacobin and CounterPunch

Pingback: A Great Way To Organize a Book - PM Press