Hoffa, Racism, and the Teamsters: The 1945 Detroit Mayor’s Race

By Joe Allen

As many people know by now, I’ve been looking into the historical relationship between the Teamsters and the State of Israel for a few months. Several online outlets including Counterpunch and the Stansbury Forum posted my original article The Teamster Connection: Apartheid Israel and the IBT. My interest in the subject was sparked by growing calls by many U.S. based unions for a ceasefire in Gaza. So far, neither the leadership of the Teamsters or any of its local affiliates or the longstanding reform group Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) have called for a cease fire, and have, in fact, opposed such resolutions.

One important stage in the evolution of the Teamster’s relationship with Israel was a testimonial dinner thrown for Jimmy Hoffa in April 1956. It was a major attempt to clean up Hoffa’s odious public image. The proceeds of the dinner were donated to the building of a children’s home in Israel. He was not yet the nationally known and notorious figure that he became following his appearance before the Senate Rackets Committee hearing in 1957. But, his thuggery and relationship with gangsters, however, were well-known in the labor movement, and, especially, in Detroit, his home base.

Curious, I decided to dive deeper into Hoffa’s lesser known but important resume building activities: his role in defeating UAW-CIO leader Richard Frankensteen’s run for mayor of Detroit in 1945. The 1945 Detroit mayor’s race is a real education in the deglamorization of Jimmy Hoffa, especially on the question of fighting racism. While Detroit witnessed much rank and file opposition to the UAW’s no-strike pledge, it also saw hate strikes against black workers and racist rioting over housing. With the war over, Detroit’s 1945 municipal elections saw any parameters of “wartime unity” erased.

According to an article in The Public Opinion Quarterly, written soon after the election, captured the brawl in its introduction:

Faced with the threat of a liberal candidacy of the UAW-CI’s Frankensteen, conservative forces in Detroit resorted to anti-Negro, anti-Semitic, and anti-“Communist” propaganda to elected their candidate, Jeffries, in one of the “most vicious, nasty campaign” in recent municipal history.

The Teamsters supported the incumbent Mayor Edward Jeffries, who ran a race-baiting campaign to defeat Frankensteen. The UAW and the Teamsters were bitter and contentious rivals in Detroit as well throughout Michigan and the Midwest. The Teamsters were prepared to use the most unsavory methods and make alliances with the most reactionary forces to defeat the UAW-CIO But, it’s not just a story of Teamster sabotage but also Frankensteen’s self-defeating strategy, especially, his failure to squarely fight racism in Detroit.

The Teamsters Role

According to Teamster historian Thaddeus Russell, the Detroit Teamsters in 1945,

“maintained their policy of opposing any candidate backed by the CIO. In the 1945 mayoral election, the CIO put its full weight behind an effort to elect UAW vice president Richard Frankensteen. As the national [CIO] PAC (Political Action Committee) and state and local CIO bodies pumped more than $200,000 into the Frankensteen campaign, the Teamsters did not hesitate to endorse the incumbent Jeffries.”

A publicly circulated letter by the Detroit Teamsters signed by Hoffa, Bert Brennan, and Joint Council President Sam Hurst endorsed Jeffries.

The Teamsters and the American Federation of Labor (AFL) were thrown into a panic after Frankensteen won the largest share of votes in an eight person non-partisan primary in August 1945. Frankensteen was projected by the UAW-CIO as a “labor candidate” since the non-partisan nature didn’t require a party affiliation, even though he had a long history of involvement in Democratic Party politics. For example, as recently as 1944, he was a delegate to the Democratic Party convention.

Again, according to Russell,

“When Frankensteen scored an impressive victory in the primary, the concerted effort of the CIO behind his candidacy caused the Wayne County Federation of Labor [WCFL] to abandon its longtime opposition to Jefferies and finally agree with the Teamsters on the threat of the CIO’s entry into politics.”

For Russell, “The WCFL’s opposition to Frankensteen along with the vigorous Teamster campaigning and Jeffries’ race-baiting proved to be a winning combination among Detroit’s white working class, who reelected the incumbent by a margin of 56,000 votes.” Vigorous campaigning, indeed. Dan Tobin, the Teamsters national president at the time, wrote in the December 1945 issue of The International Teamster magazine in December 1945, “Frankensteen was defeated by only 56,000 votes. The Teamsters supported his opponent, Mr. Jeffries, not because they were in love with Mr. Jeffries but because we could not afford to support Frankensteen.”

Apparently, the Teamsters had enough affection for Jeffries and his sordid campaign by rewarding him with a major mobilization of Teamster members, family, and friends to the polls. Tobin boasted:

“The membership of the all of the local unions of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters in Detroit is close to 25,000. Each man was expected and almost commanded to bring one other vote to the polls besides his own. That would be his wife, his sister, his brother or some friend. That would make a total of 50,000 votes, which undoubtedly were delivered against Frankensteen. Some of the other American Federation of Labor not as large in membership as the Teamsters did the same.”

A Knight in Dull Armor

Even if Tobin’s vote count is off by a few thousand votes, the Teamsters role in the re-election of such a racist demagogue as Edward Jeffries is horrendous. But, there is more to the story, including Frankensteen’s hapless campaign. Dubbed “A Knight in Dull Armor” by Time magazine, Frankensteen proved continually unable to defend himself from a hailstorm of attacks and stupidly distancing himself from his trade union background, despite a much larger turn out of voter than the last time the UAW-CIO put forward a labor slate in 1937. Over 500,000 voters turned out in 1945, significantly larger than the 400,000 in 1937.

Writing as Martin Harvey in Labor Action newspaper, Martin Glaberman focused on several critical failings of the Frankensteen campaign. First, according to Glaberman was:

“During the whole campaign the initiative was in the hands of the reactionary Jeffries. It was he who determined the issues and set the tone of the campaign. Outstanding in the issues presented by Jeffries was the race question. Jeffries organized a widespread undercover anti-Negro campaign which surpassed his vicious use of the question in the last municipal election. The central idea was white supremacy in the City Hall and the maintenance of the “purity” of the all-white neighborhoods.”

Jeffries campaigners and supporters among white homeowner associations also, according to Harvey/Glaberman:

“distributed leaflets in Negro neighborhoods charging Frankensteen and the UAW with being anti-Negro. In the same way they initiated a whispering campaign charging that Frankensteen was Jewish, yet distributed newspapers in the Jewish neighborhoods charging Frankensteen with being a friend of Father Coughlin and an anti-Semite. Even the regular daily press gave support to this campaign by featuring prominently news items on the extent of Frankensteen’s Negro support and charging repeatedly that Frankensteen represented only a minority of the population.

“The second major issue,” according to Glaberman , “in Jeffries’ campaign which was constantly combined with the first was the “red scare” and the charge that the CIO wanted to take over the city. On both of these issues Frankensteen devoted his time to denying the charges. He did not represent the Negroes, he said, but all the people. He was not a red and the CIO did not want to take over the city. He offered no program for the Negroes to put an end to the discrimination and segregation to which they are subjected and he offered no program to labor or the people as a whole on the many vital problems which exist, foremost among them being jobs and security.

Frankensteen was reduced to “only positive statements were devoted to presenting himself as more efficient, as more concerned with improved bus service and cleaner alleys.” Glaberman summarized Frankensteen defeat:

“Without an aggressive program, for labor and the people, without calling on the middle class to support labor in this program, it was impossible for Frankensteen to answer the viciously reactionary charges of Jeffries. If his denials are valid, that is, if he does not represent labor but “all the people,” then why should anyone support him rather than Jeffries, who claims the same thing? If his denials are not true, that is, if he does represent labor, then why should the middle class, the storekeepers, the professionals, etc., support Frankensteen when they see no difference between “labor’s” program and Jeffries’ program?”

The 1945 Detroit municipal elections have fallen down the memory hole for the U.S. Left. It deserves a more extensive research and writing.

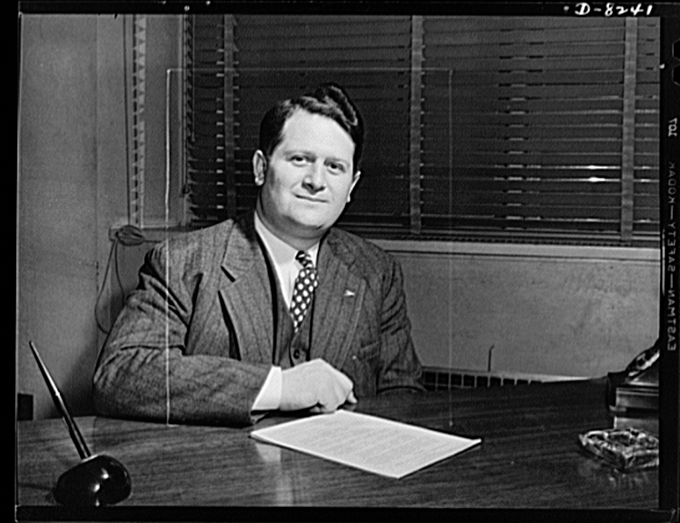

Richard Frankensteen

Profile: Detroit News profile, 1997.

Backed by UAW President Homer Martin, Frankensteen won the vice-presidency of the international union in 1937. But in 1939 Martin was ousted as president by R.J. Thomas, and Frankensteen lost as well.

During World War II he was appointed to the National War Labor Board and the National War Production Board by President Franklin Roosevelt. He was appointed by Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) President Philip Murray in 1941 as national director of efforts to organize workers in the expanding aviation industry during the war years. He retained the post when the UAW was given jurisdiction over the industry in 1942.

The power struggle turned ugly at the UAW’s convention in 1943 in Buffalo when Reuther delegates attacked Frankensteen and George F. Addes, secretary-treasurer of the UAW, for their support of piecework and incentive pay in auto plants. The Reuther faction circulated a campaign ditty to the tune of an old ballad, “Reuben and Rachel,” that suggested Frankensteen and Addes were taking orders from Joseph Stalin.

The verse went:

“Who are the boys who take their orders

Straight from the office of Joe Sta-leen?

No one else but the gruesome twosome,

George F. Addes and Frankensteen.

Who are the boys who fight for piecework,

To make the worker a machine?

No one else but the gruesome twosome,

George F. Addes and Frankensteen.”

Other verses, some unprintable, added spice to the doggerel.

In the end, the convention endorsed a Reuther resolution opposing piecework and incentive pay and Reuther defeated Frankensteen in a race for first vice-president. Addes narrowly kept his office.

At the 1943 UAW convention in Buffalo, Frankensteen was elected first vice-president of the UAW.

Frankensteen was a Wallace supporter at the 1944 Democratic convention.

From Tom Sugrue, The Origin of the Urban crisis, page 80:

“Several Detroit politicians used the housing issue to their advantage in the reelection bids later that year [1945], incumbent Mayor Edward Jeffries, in a campaign laden with racial innuendo, attacked UAW-backed mayoral candidate Richard Frankensteen, flooding Northwest and Northeast Side neighborhoods with literature warning of his opponent’s support for public housing and ties to black organizations.”

“Jeffries and his supporters combined anti-black and anticommunist sentiments into a potent political brew. Frankensteen, warned Jeffries and his supporters, was a “red” who would encourage “racial invasions” of white neighborhoods. Unlike Franksteen, Jeffries would uphold community interests. “Mayor Jeffries is Against Mixed Housing,” proclaimed a boldly printed campaign poster. It quoted Jeffries: “I have tried to safeguard your neighborhoods in the character in which you, their residents, have developed them.” The Home Gazette, a Northwest Side newspaper, editorialized that “There is no question where Edward J. Jeffries’ administration stands on mixed housing.” It praised the Detroit Housing Commission for “declaring that a majority of the people of the city of Detroit do not want the racial character of their neighborhoods changed, and for reiterating “its previous stand against attempts of Community-inspired Negroes to penetrate white residential sections.”

Black observers of the election and union supporters of Frankentseen were appalled by the blatant racial claims of Jeffries’s campaign, and at attempted to use economic populist and anti-Nazi rhetoric to deflate Jeffries’s charges. Henry Lee Moon, writing in the NAACP’s monthly, Crisis, accused Jeffries of appealing “to our more refined fascists, the big money interests, the precarious middle class whose sole inalienable possession is a white skin.” Jeffries’s racial appeals were remarkably successful. They bolstered his flagging campaign, and gave him a comfortable margin in November against UAW-backed candidate in a solidly union city. On the local level, the link between black and red was a clever for attracting white Democrats, suspicious of liberalism and its capacity for egalitarian political and social rhetoric.

Public housing is “Negro housing.”

Lichtenstein, page 235:

“Most significantly, the fault lines that had long divided autoworkers according to race, ethnicity, skill, and politics were now deeply buried within a larger commitment to the union and its cause. These divisions had not disappeared, of course: Richard Frankensteen’s unexpected defeat in November’s [1945] mayoral election had demonstrated the capacity of those forces backing Mayor Edward Jeffries to use racist and anti-Semitic innuendo and outright slander to pry Polish and Italian voters from the CIO, even in solidly working-class neighborhoods.”

Halpern, UAW Politics, 42-43:

“In the municipal elections, Frankensteen won 44 percent of the total ballot, somewhat more than the labor slate won in 1937. He took 61 percent in Polish working-class neighborhoods and 75 percent in Italian precincts. But the relative decline in their loyalty proved the margin of defeat for the CIO, which had never won more than half of the votes of those who lived in Irish or southern white sectors of the city.”

Time magazine, October 29, 1945

POLITICAL NOTES: Knight in Dull Armor

Monday, Oct. 29, 1945

When hulking Richard Truman Frankensteen was nominated for mayor of Detroit, many a U.S. left-winger got excited. Frankensteen was a founder and vice president of the vast United Automobile Workers, C.I.O. He had bled at the hands of Ford “service men” at the famed Battle of the Underpass in 1937. He also seemed to have some political sex appeal: he was a college man (University of Dayton ’32), a ready speaker, young (38) and did not mind admitting that he wrote operettas, collected dolls as a hobby. If U.S. labor was to produce, not merely influence poli. ticians. perhaps Frankensteen would lead the way.

But last week, as Detroit’s final election drew near, Dick Frankensteen looked less like a trail blazer than a man just feeling his way around in a lot of trees. He had spoken as few ringing words about labor as possible. The reason: even his enemies in the union wanted him to be mayor (and thus out of union officialdom) so there was little point in it. Instead, to woo the public, he harangued audiences about Detroit’s dirty alleys, its street-railway fares, tried hard to be everyman’s friend.

Target Elusive. None of this was very exciting. As every city boss knows, candidates should make great promises, roar for reform or sail into their opponents, particularly incumbent opponents. Frankensteen found that attacking his opponent, Mayor Edward J. Jeffries, was disconcertingly like shadow boxing. In six years as mayor, Jeffries had done little, had made few bad mistakes.

But the mayor found 206-pound Dick Frankensteen a target hard to miss. He charged that U.A.W.’s man was suppported by Communists and rabble-rousers, would run the city for a little group of labor chieftains. Smear pamphlets appeared on Detroit’s streets. Hecklers asked Frankensteen embarrassing questions about housing for Negroes, his plans for non-union city employes.

Losing ground, Frankensteen made dramatic attempts to settle the crucial Kelsey-Hayes strike. He failed to produce any dramatic results. Meanwhile the muddled state of Detroit’s labor affairs did nothing to improve his standing in the public eye. Last week Detroit politicos guessed his chances were no better than 50-50 (though he had drawn 82,936 primary votes to Jeffries’ 68,754), that he would win only if Detroit had a strong, last-minute impulse to throw out his opponent.

…

You can read more from Joe Allen on Medium