Press power of the Long 1960s: Liberation through duplication

By Lincoln Cushing

Social justice printing history in the United States during the “long 1960s” – describing the period from the early 1960s through the later 1970s – is not one of skilled craft or precious publications. It’s a history of young, passionate amateurs learning new skills and new technologies as a means to an end.

Several factors converged to produce a massive outpouring of printed documents. First, there was the baby boom – by 1969, 19 percent of the U.S. population was between 14 and 25 years old – an increase of 44 percent over this age group in 1960.[i] Young people were finding their voice and had something to say. The civil rights movement here was being matched by vigorous national independence movements around the world. The period was intoxicating and full of optimism.

But how to get the word out? Most standard print shops were either too expensive for broke students or simply wouldn’t touch the radical materials that were brought in. Some of the content could draw the unwanted attention of authorities. So activists learned to print for themselves. Here’s how the mainstream media described it:

The information officers of the New American Left have rediscovered an ancient political ally: print power. All over the country, radical and “movement” organizations have spawned their own print shops run by their own pressmen to churn out an increasing number of posters, pamphlets, handbills, and flyers. Whether it’s to mobilize a march on Washington, explain the advantages of “Free Speech” for GIs, or advertise courses at an alternative university, the rebel presses are rolling. By the thousands, their folded-and-stapled brochures, decorated with crude graphics, are being given away at hastily set up campus tables or sold in the standard subculture outlets.[1]

The equipment included small offset presses (Multilith 1250s and AB Dick 360s were ubiquitous) that were simple to learn and operate. Silkscreen printing saw a renaissance, using hand-cut lacquer-based stencils and oil-based inks. And one new technology, the electric stencil-burning Gestefax, was transformative in supporting community-based communications.

The Gestefax, introduced in 1959, was the first device that allowed consumers to scan original art to run on a Gestetner. This was a mechanical duplicator on which a stencil master mounted on an ink-filled drum printed pages up to 8 ½ x 14”. Instead of needing a typewriter to pound out a stencil, any art – even a photo – could be scanned on the dual rotating drums of the Gestefax, one with an electric eye skimming the original and the second burning the stencil with an electric spark. It was so simple to use that ads noted “it can be operated by your office girl, without any training.”[ii]

This scanner, coupled with the fact that by swapping or cleaning the ink drums one could print multiple colors in subsequent passes, offered some of the earliest opportunities for grassroots artists and organizers to make colorful flyers and newsletters. It may be hard to believe in this day and age, when “color separation” isn’t even a conscious act and photographs can be effortlessly published on a Web page, but this clunky technology was a breakthrough aesthetic boon to democratic media.

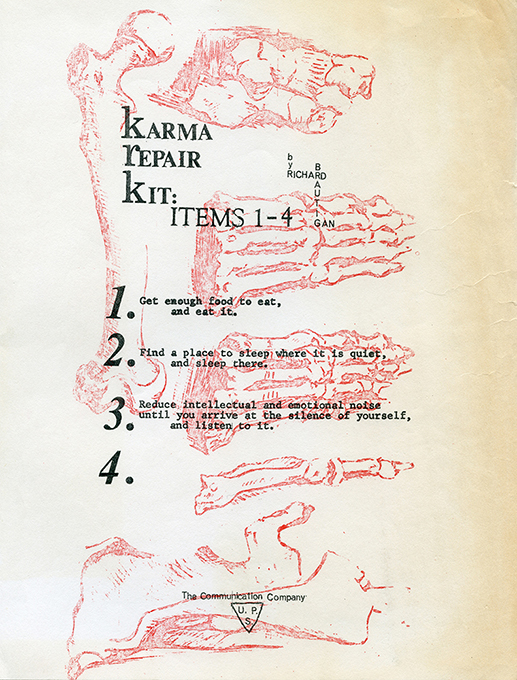

One of the first to experiment with the artistic possibilities of these machines was the Communication Company (or “Comm Co”), founded in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district by Chester Anderson and Claude Hayward in January of 1967. This was the epicenter of the new counterculture, and every movement needs a medium. The Communication Company cranked out an endless stream of flyers and handbills for community groups such as the San Francisco Mime Troupe and the Diggers as well as scores of events. As their promotional flyer stated, they planned to “Provide quick & inexpensive printing services for the hip community.” They also aspired to “Produce occasional incredibilities out of an unnatural fondness for either outrage or profit, as the case may be” and to “Do what we damn well please.” Years later one Comm Co participant described the chutzpah of this printing adventure:

We took [samples of our] sheets to the Gestetner company. They had no idea that their machines were capable of doing what we did. Like we put a peacock feather on the Gestetner and put the top down and Xeroxed it in color. And they were amazed. They were very beautiful sheets. We asked the Gestetner company to let us keep their machine, which hadn’t been paid for in full, and they said, No. So we liberated it.[2]

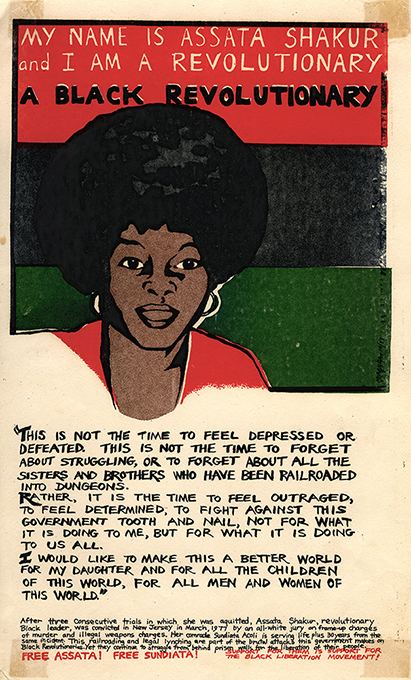

With an unsustainable business model and run by at-the-edge artists, the Communication Company lasted less than a year, but its flyers set the bar for artistry in street propaganda. Ten years later, another Gestetner art movement blossomed in the Bay Area. In the late 1970s, a critical mass of neighborhood arts organizations and community-based artists were prolifically making murals, posters, theater, and other cultural forms. A report produced about the S.F. Neighborhood Arts Program noted: “Uncontestedly, NAP’s design and printing of colorful flyers for community arts activities is the program’s best-known service…An average day’s output includes design of two to four flyers and printing of eight editions, many designed by the requesting group, of from 500 to 1000 each. They run through about 120,000 pages monthly.”[iii] Once again, the lowly Gestetner and Gestefax came to the rescue in helping spread the word, and in some cases, be the word.

Screen printing was quickly adopted by activists as a simple and effective way to create large and colorful posters. When Paris art students wanted to support the workers’ general strike in 1968, they quickly abandoned the clunky lithography they were taught in school and began screenprinting after one participant shared the “American printing” process he’d learned at a gallery job.[3] Like Gestetner, screenprinting is a stencil process but is printed by hand using a squeegee to push the ink through a framed stretched fabric that supports the image. Stencils can be hand cut with no machinery required. The resultant huge body of simple and strong street posters inspired artists around the world.

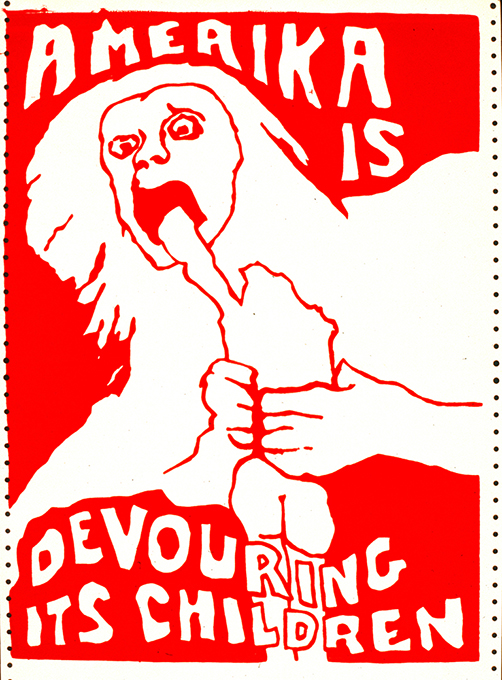

After the antiwar student demonstrations and killings at Kent State, Ohio (May 4, 1970) and Jackson State, Mississippi (May 14, 1970) there was a massive upswelling of resistance culture in the United States. Political poster workshops blossomed all over the country to express public outrage. At the University of California, Berkeley, faculty at the College of Environmental Design encouraged the use of campus facilities for a short-lived workshop that created an estimated 50,000 copies of hundreds of works. Many of these were screenprinted on distinctive discarded tractor-feed computer paper from the computer labs.

Conventional offset printing was a key tool of political movements as well. Occasionally older radicals in the trade would share their skills and equipment, but more often than not activists simply learned on the job and did the best they could.

The first glimmer of the new generation of activist print shops started in 1964 in the heat of Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement (FSM). Their newsletter was first printed on a 14” x 20” Multilith 2066 by in the basement of a home later demolished to make People’s Park. The press was owned by Dunbar Aitken, publisher of the occasional science journal Particle, but Dunbar was evicted by his landlord for printing “communist papers.” When FSM activist Barbara Garson got involved, the shop was being managed by an old Trotskyist printer. Barbara describes the scene:

Deward Hastings, a speed freak who was handy with equipment, got [the old press] running… We printed five or six issues of the FSM newsletter. The press did movement printing at cost. That was in the day of marches and demos with huge print runs of leaflets. We also took in commercial business at normal prices. But it was understood that in a political emergency the political jobs would come first.

The first generation of shops blossomed in 1967. In addition to Peace Press in Los Angeles, several other printers dedicated to social change began inking their cylinders.

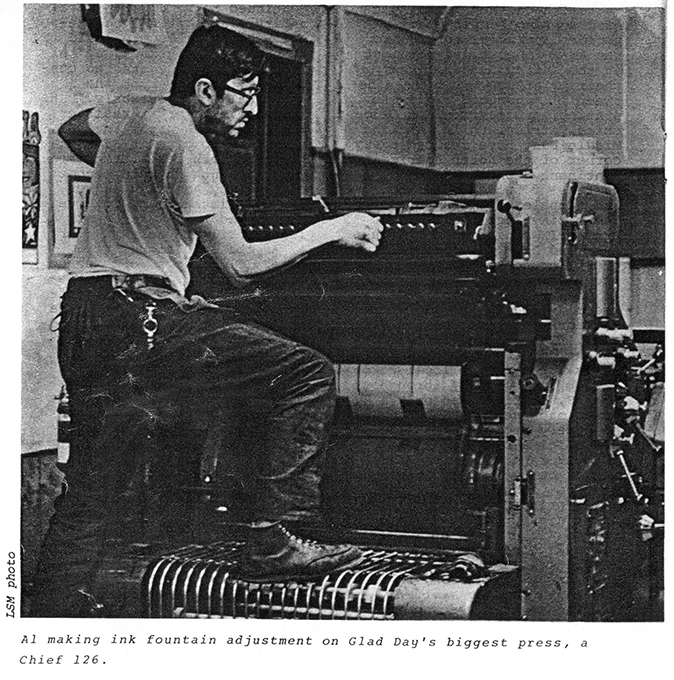

Glad Day Press was founded in Ithaca, New York as a spin-off from the local peace center. The name was from William Blake’s 1795 painting, where Da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man” is liberated from his constraining circle and square, beaming with an inner energy – an apt metaphor for the transformative feeling of the mid-1960s. They bought used equipment, learned to print, and served as a model for an independent activist shop. Although their initial priority was opposing the war in Viet Nam, they weathered shifts within the movement, including the disintegration of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the end of the war in 1973, and continued to produce materials for a wide range of issues including Cuba solidarity, Native American occupations, and support for liberation movements in Southern Africa. They charged a sliding scale and produced many self-published projects, including posters and books. As they began to take on more commercial printing to sustain the shop, they relied less on volunteers and cross-trained a core group of skilled collective members, and proudly displayed the militant union label of the Industrial Workers of the World.

Also in 1967 Madison, Wisconsin, publisher Morris Edelson donated the profits from his production of Barbara Garson’s satirical play MacBird for the purchase of a used Multilith 1250 duplicator. This became the first movement press in the area.

Sometimes political organizations chose to handle their own printing. The Black Panther Party operated an offset press in San Francisco and Oakland from 1968 to 1978. Although primarily used for printing BPP flyers and posters (except for their newspaper), this shop did handle occasional work for other progressive causes. The first BPP printing operation was at the national distribution office in San Francisco, which was set up by young Panther Benny Harris. Benny had recently restored an industrial shoe stitcher and was invited to help out at the print shop, where the equipment needed mechanical attention. He described the scene:

After arriving at the SF distribution office, I saw two old and incomplete Chief 20 printing presses sitting side by side on the concrete floor. After examining them and discussing what was required to rebuild them, I decided to take on the challenge. I did not have any knowledge of the printing process but I did have the required mechanical skills to do a rebuild of the presses. A few months later with one machine used for spare parts, the rebuild was complete. One functional Chief 14×20” printing press was up and running. After receiving a few lessons on the basics of printing, I was left on my own to develop my printing skills. Emory Douglas [“Revolutionary Artist and Minister of Culture” for the BPP] also provided me with valuable artistic guidance and proper artistic layout etiquette. My printing skills gradually developed over time as the press was used to print flyers, posters, pamphlets, restaurant menus, and business cards.[4]

More movement shops sprang up in almost every major city. Madison’s second shop, RPM (Revolutions Per Minute) Print Co-op, got its start in 1970 with a grant from the Wisconsin Student Association to buy out an existing commercial printer. Salsedo Press incorporated in Chicago in 1973 (and lasted until 2021). The next year saw the triple birth of Red Sun in the Boston area, Resistance Press in Philadelphia, and Inkworks Press in Oakland (later Berkeley). Other shops of this vintage include New York City’s Come!Unity Press (a 24-hour open access print shop run by a gay anarchist collective), Fanshen in San Diego, People’s Press in San Francisco, and Northwest Working Press in Eugene, Oregon.

Most of these shops embraced a distinct set of qualities:

● An articulated political position;

● A sliding scale for fees and specific mechanisms for donated work;

● A commitment to hiring people not usually in the trade (women and people of color);

● Membership in a trade union;

● Organization in a non-hierarchical form, such as a collective or co-op.

Berkeley’s Inkworks Press was formed in 1974 by several members who had been learning offset printing at an alternative school and wanted to create a movement print shop. From the beginning, the shop planned to be self-sufficient, which would be accomplished with a blend of commercial and political work charged on a sliding scale. As a mechanism to institutionalize revolutionary politics, the shop became a non-profit (though not tax-exempt) corporation with a collective structure in which everyone owned it together – no one owned any individual share, as is the case with co-ops. As a way to assure reasonable working conditions and align with the labor movement, Inkworks became a union shop (International Printing and Graphic Communications Union, later Teamsters) in 1978. One of the long-lasting movement press giants, Inkworks closed down in 2015 – it had become hard to recruit new members willing to take on collective responsibilities and the rapidly-changing printing trade had become more competitive..

After the military draft ended and the Viet Nam War collapsed, much of the wind was taken out of the sails for movement printing. But American capitalism and imperialism lumbered on, and a whole new set of issues – among them, women’s liberation, gay rights, U.S. proxy wars in Latin America, South African apartheid – emerged that also required printing. Artists and activists continued to learn the various technologies for generating effective propaganda. Current social justice print shops include Community Printers in Santa Cruz (California) and Radix Media in Brooklyn.

The radical printing of the “long 1960s,” ragged and chaotic though it may have been, was a powerful testament to the importance of document duplication in support of liberation. Long live the power of the press!

Images:

“Karma repair kit” Gestetner flyer by Richard Brautigan, printed by the Communication Company, circa 1967

.

“My name is Assata Shakur and I am a Black revolutionary” Gestetner flyer by Miranda Bergman, 1977 (printed by Jane Norling).

.

“Amerika is devouring its children” screenprint by Jay Belloli, 1970, UC Berkeley poster workshop

.

“[Al] Ferrari making ink fountain adjustment on Glad Day’s biggest press, a Chief 126” in “Left profile: Glad Day Press” Liberation Support Movement Newsletter, Winter 1978

.

Bennie Harris at Black Panther Party print shop, San Francisco, circa 1969

.

First published in Printing History Number 33, Summer 2023, the journal of the American Printing History Association

…

[1] “Young Radicals Rediscover and Use the Power of the Press,” Associated Press, July 8, 1970

[2] “A University Of The Streets” Jay Babcock interview with Judy Goldhaft of the San Francisco Diggers, September 9, 2021, Digger Docs

[3] “Anti-Nazism and the Ateliers Populaires: The Memory of Nazi Collaboration in the Posters of Mai ’68”

Gene M. Tempest, thesis prepared for the B.A. in History, U.C. Berkeley, 2006. https://www.docspopuli.org/articles/Paris1968_Tempest/AfficheParis1968_Tempest.html

[4] e-mail from to Benny Harris, 2/2/2011

[i] “Characteristics of American Youth,” United States Census report P23-30, February 6, 1970.

[ii] “George Stuart Stocks Newest in Equipment,” Orlando Evening Star July 9, 1970, p. 11

[iii] “The San Francisco Neighborhood Arts Program,” Interviews Conducted by Suzanne B. Riess for The Bancroft Library in 1978, p. 212