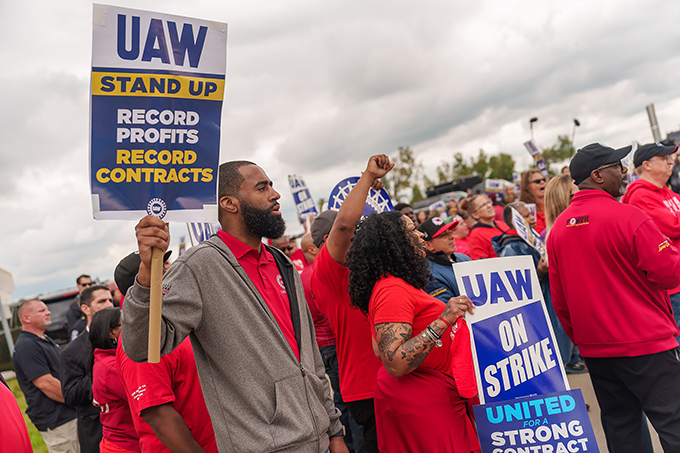

The UAW Strike, As of October 9, 2023

By John Womack

The Stansbury Forum is proud to publish a brief analytical piece by John Womack on the ongoing UAW selective strikes against the Big Three domestic auto producers, Ford, GM and Stellantis (Chrysler Fiat)! PM Press recently published a book featuring interviews with Womack, entitled Labor Power and Strategy. John applies some of that analytical acumen in looking at the UAW actions. Since John penned his article on October 9 the UAW has extended the strike to the giant Ford Kentucky Plant that is the company’s most profitable operation. Peter Olney/Co-Editor of the Stansbury Forum and Labor Power and Strategy

Some 1,700,000 people now work in the automobile industry in the USA. About 150,000 are members of the UAW, mainly in Michigan, Ohio, and Indiana. The union has a strike fund of $825,000,000. If all the UAW workers went out on strike, it would exhaust the strike fund in about 90 days. When the strike began on September 15, Stellantis (Chrysler-Fiat-Peugeot) had 74 days of unsold inventory; Ford had 64 days of unsold inventory, and GM had 50 days.

The UAW had dramatic demands for a new contract: a 40% wage increase (which compounded would amount to 46% over the life of the contract, now reduced to 36%), a four-day work week with 40 hours pay, COLA, the abolition of tiers, union jobs in the electric-vehicle plants the companies are planning, over $100,000,000,000 to be invested in EVs, making 1,000,000 new jobs, about half in the still union-weak South.

The first three plants the UAW struck were GM’s at Wentzville, MO, near St. Louis, Ford’s plant at Wayne, MI, west of Detroit, and the Stellantis plant at Toledo. They were all assembly plants:

- Wentzville made GMC Canyon and GMC Colorado pickups, big money-makers

- Wayne made Bronco SUVs and Ranger pickups, again big money-makers

- Toledo made Jeep Wrangler, SUVs and Jeep Gladiator pickups, again big money-makers.

All told only about 13,000 workers were out, drawing strike pay from the union’s strike fund.

This shows the initial nature of the strike. First, it was a selective strike. It is therefore reminiscent of the Association of Flight Attendant’s intermittent strikes in 1993 against Alaska Airline, when only about a total of 25 workers in various cities over several days walked off one flight after another, causing the airline much trouble and big losses and soon giving the AFA a historic win. The UAW can’t do intermittent strikes. Once it strikes, it has to stay out to the end. But it can do the selective strikes it is doing. For example, if Wentzville, Wayne, and Toledo fail to win the battle, the union could call workers out at other big money-making plants, like GM’s Arlington Assembly Plant, which makes Cadillac Escalades; or Ford’s Kansas City or Dearborn plant, which makes F-150 pickups, or Stellantis’s Stirling Heights or Warren Truck Assembly, which make RAM 1500s.

Second, the choice of this initial strategy is in line with Tom Juravich’s concentration of striking profit centers, striking places where the company makes most of its money. That’s what they study and teach at his UMass Amherst Labor Studies Center, where Olivia Geho staffs a Strategic Corporate Research website.

This selective strategy is different from what Peter Olney, Glenn Perusek, and I argue in our new book, Labor, Power and Strategy. There I focus on what I call technically and industrially strategic positions in the division of labor at work, bottlenecks in the flow of production, choke points. I argue labor should try to hold these positions and use them to disrupt production and bring the boss to see the union’s reason–and power. It is the power workers hold over production and the good they can get from it.

Nowadays, I think I read in The Wall Street Journal, the average internal-combustion automobile has about 30,000 parts, all of which it needs for the average buyer to buy it. Some parts are absolutely essential, like transmissions. GM has five transmission plants of its own, at Bedford and Kokomo, IN, Romulus and Saginaw, MI, and Toledo. Stellantis has three such plants of its own, two in Kokomo and one in Tipton, IN. Ford has only two, one at Livonia, MI, and one at Sharonville, OH. These are technically highly strategic plants. If the UAW strikes them, that in effect closes all the plants that need the transmissions.

It seems to me the UAW at first decided to put their strike fund against Stellantis, Ford, and GM inventories, reasoning that if they did their selective strikes they could run down their strike fund more slowly and outlast the companies. The companies figured they could last longer than the union and did not surrender. But on Friday, September 22, the union expanded the strike to 38 more plants, none at Ford, which had made gone some way to meeting the union’s demands, but at 18 GM plants and 30 Stellantis plants, 38 places closed in 20 states, 8,000 more workers striking (and drawing strike pay). This was a significant expansion, not only because of the numbers, but because these were all distribution centers, basically warehouses that received parts from parts manufacturers and

distributed them to assembly plants. Not many workers were out, but these were all highly strategic plants, choke points in the flow of auto and truck production.

The UAW had indicated it might call out more workers at more plants [and now has extended the strike to the giant Ford Kentucky Plant, the company’s most profitable operation.]

We are now over three weeks into the UAW’s action. Over 25,000 members out of 146,000 are out on strike. The strike fund is still very strong. And the choke points are making the companies’ inventories ever tighter.

The rest of us, pulling for the union, can only wait and see who caves.

…

Pingback: Strategy, the Movement and Power: Debating Labour and Community Organizing - PM Press