“A World in Common” – A Review of the TATE photography exhibit

By Stuart Freedman

As those of us who have spent a lifetime trying to use photography as an (albeit imperfect) instrument of change, the reflection that the medium itself was originally central to the European conquest of others is an irony that cannot be ignored. Or unseen.

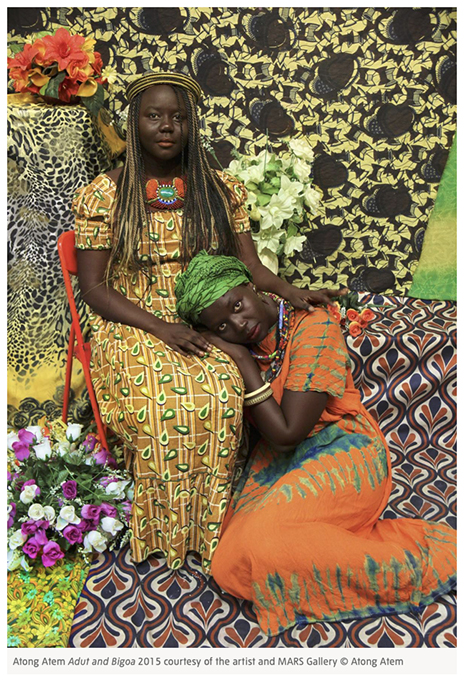

It is these historical representations that Tate Modern’s show, A World in Common, seeks to confront and engage with. This is the gallery’s first major exhibition that explores contemporary photographic practice from that continent reimagining what Africa is, was – or might be – as seen through the eyes of some of its own artists.

Comprehensive in scope and featuring a mixture of photography, video and installation, it exposes work from thirty-six artists delineating narratives from an enormous, almost unimaginable territory that is at turns recognisable, unfamiliar, thrilling and baffling in equal measure. It is a noble aim but ultimately its breadth is also its weakness.

The show opens with George Osodi’s stately portraits of Nigerian Queens, Kings and Gods, that uncomfortably (and presumably unintentionally) echo the class basis of imperial monarchical rule in a visual language that is redolent of Victorian portraiture.

Indeed, by and large the show leaves open the question of who has the power to record the lives of others and here it is largely the gaze of Africa’s new urban middle classes that replaces a Western one. That said, the interiority of that gaze undeniably expresses what Jennifer Bajorek has referred to as “the urgency of African and Black futures.”

It is to those complex and myriad futures – and to the aesthetic of Afrofuturism (first coined way back in 1993 by Mark Dery) – that the show tries to point. Which is all the more confusing when the (white) Spanish photographer Christina de Middel’s imaginative fiction, Afronauts (about the Zambian space project) is included on the walls. Kiluanji Kia Henda’s ephemeral installations in the Namibian desert to

comment on Luanda’s construction boom is questioning but it is Kiripi Katembo’s Un Regard (2008-13) using dreamlike puddle reflections of Kinshasa that is a real showstealer. These imagined sets contrast with the of ‘counter-histories’ of Lazhar Mansouri’s Portraits of Aïn Beïda (c.1950s-70s) and Santu Mofokeng’s The Black Photo Album / Look at Me (1997) asks different (and sometimes tricky) questions about historic self-representation.

It is the show’s engagement with Africa’s spiritual world however that is the most dense and beautifully ambiguous. The spiritual remembrances especially in Khadija Saye’s in this space we breathe (2017), explore and re-enact the profound rituals in her own mixed faith background. This (literally) haunting work from Saye, a young

Gambian-British artist who perished in the Grenfell fire at only 24, reminds us what a talent that shone brightly and was lost. Em’kal Eyongakpa’s Ketoya speaks #1, (cluster II), 2016 – photographs of Cameroon’s sacred lands (a site of significant resistance to German colonialism) is a darkly haunting document of struggle and memory. Maïmouna Guerresi’s Sufi inspired work, M-eating – Students and Teacher, 2012 couldn’t be more different – full of colour and geometry but equally engaging.

The last piece, JulianKNXX’s In Praise of Still Boys, 2021 is an extraordinary finale that combines poetry, film and music that unites the artist’s memories of growing up in Sierra Leone, war and slavery. Narrated by his mother in her native Krio, it fittingly imagines a stepping-off point, both physical and psychic from a past that is open and yet to be imagined.

A World in Common is on show at London’s Tate Modern until January 14th 2024.

…