The Terrible Emptiness of “Oppenheimer”

By Alicia Inez Guzmán, Searchlight New Mexico

The blockbuster movie leaves out the real story’s main characters: New Mexicans

This piece was reported and first appeared in Searchlight New Mexico

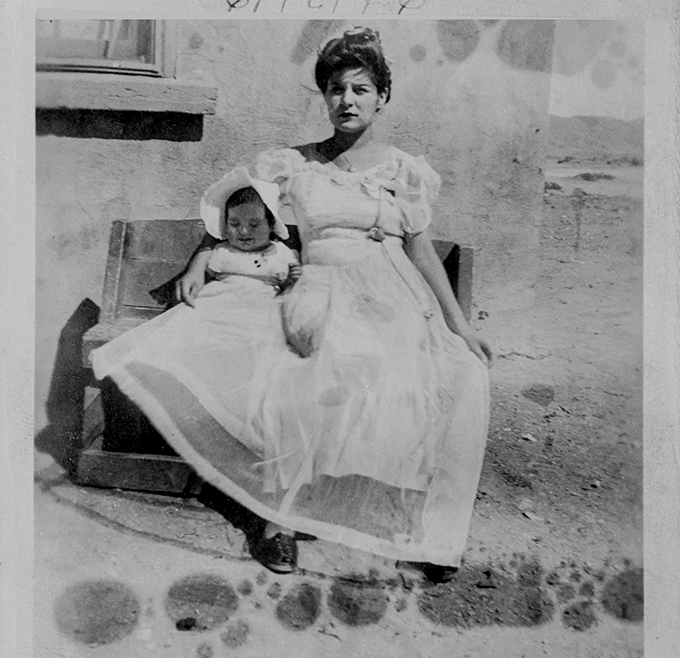

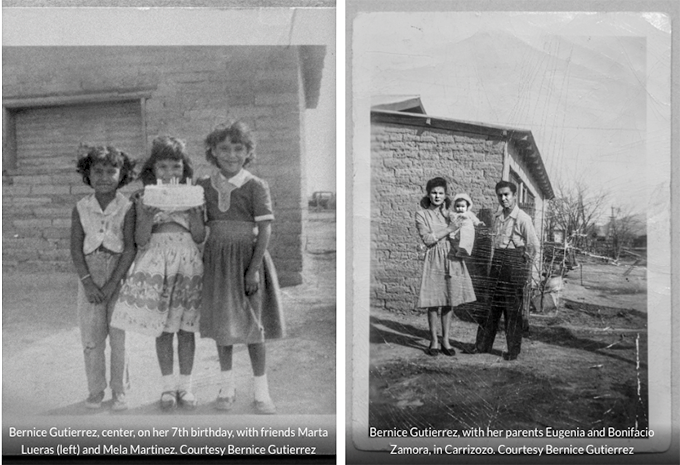

Bernice Gutierrez was eight days old when a light 10,000 times hotter than the surface of the sun cracked open the predawn sky. No one in south-central New Mexico knew where it came from, or that the tiniest units of matter could be split to unleash such energy. Nor could they know that when the cloud that followed bloomed some 50,000 feet into the sky, it was surrounded for the briefest of seconds by a blue halo, the “glow of ionized air,” as the Manhattan Project physicist Otto Frisch described it.

The impacts of that unholy halo were all too apparent in the years after, when her great-grandfather died of stomach cancer. One person after another would receive their own wrenching cancer diagnoses — 41 people in her immediate family, spanning five generations. Every one of them had lived in the Tularosa Basin and within 50 miles of the Trinity Site, where the first atomic bomb, nicknamed “Gadget,” was detonated on the northern edge of the Chihuahuan Desert.

Gutierrez was one of a group of downwinders, including Mary Martinez White and Tina Cordova, cofounder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium, who watched the movie “Oppenheimer” together when it opened. In one scene after another, New Mexico’s landscapes unfurled — all painfully beautiful and all, it appeared, empty and unpeopled.

In New Mexico, we have lived in the blind spot of a national narrative for eight decades, repeated once again in this box office hit. Over its exhaustive three-hour run-time, it managed to avoid mentioning what we here have been sharing with loved ones at kitchen tables for decades: the violent evictions that took place on the Pajarito Plateau to build Los Alamos, the Pueblo and Hispanic men and women who did essential work for the Manhattan Project, or the thousands of New Mexicans affected to this day by the Trinity test.

To watch J. Robert Oppenheimer’s character instead create and destroy in the state’s big, beautiful and ostensibly barren lands is to deny the presence of so many people whose lives were indelibly transformed by the dawn of the atomic era and continue to be shaped by the juggernaut that is today’s nuclear industrial complex.

Oppenheimer, the son of a wealthy businessman, had come here as part of a cultural moment. He hiked, rode horses and camped. He stayed at a dude ranch in Pecos. He fell in love with and then changed New Mexico forever.

“I am responsible for ruining a beautiful place,” he would later confess.

The film, Gutierrez said, skipped blithely over the ruin. “They leave out the fact that in those isolated areas lived ranchers whose lands they took away and who were never compensated for it.”

The blast was so hot it liquified sand and pieces of the bomb into hunks of green glass. Lead-lined tanks were dispatched to take soil samples at ground zero as fallout cascaded across 46 states. Ash fell from the sky like snow for days afterward, contaminating cisterns, acequias, crops, livestock, clothing and people. At the time of the detonation, 13,000 people lived within a 50-mile radius.

‘Love-struck’ with the beauty

Oppenheimer initially arrived in New Mexico among a wave of smitten travelers. Artists, writers, dancers, anthropologists, museum boosters, health seekers and at least one psychoanalyst (Carl Jung), all had come as well-to-do tourists in search of the ineffable — landscapes, light, exotic cultures, “a patch of America that didn’t feel American,” in the words of writer Rachel Syme.

Long before he became the father of the atomic bomb, Oppenheimer was “love-struck” with the stark beauty of New Mexico, as Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin wrote in “American Prometheus,” the biography upon which the movie is based. He would later lease and then buy a home in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains with his brother, Frank. Like so many others, he’d been mesmerized by the West.

New Mexico and the Southwest had long been lodged in America’s psyche. Landscape painting and photography pictured this new and alien frontier to incoming settlers and tourists as early as 1848, the year the United States annexed the region from Mexico. The art forms ended up serving the nation’s gospel, Manifest Destiny, by portraying “uninhabited” landscapes open to settlement. At the same time, U.S. forces brutally removed Indigenous peoples and others of mixed descent from their ancestral lands.

That aesthetic was at work in “Oppenheimer,” a movie that not only played up the romance of the landscape but also made it appear that the atomic bomb test only affected an elite group of scientists watching raptly in cars and bunkers.

“That’s the thing about the white supremacist imagination, right? They create alternate realities for our lives and communities and we have to live with the consequences,” said Mia Montoya Hammersley, an environmental attorney and member of the Piro-Manso-Tiwa tribe whose ancestry includes the earliest stewards of the Tularosa Basin, where the first bomb was detonated.

“This narrative that New Mexico is this empty barren place, people still really buy into that and believe it.”

At the time of the blast, nearby towns like Alamogordo, Tularosa, Carrizozo and San Antonio were home to farmers, ranchers and railroad workers. The Mescalero Apache Reservation sits just southeast of the Trinity Site. The entire region was once an epicenter of commerce between the Pueblo communities of Northern New Mexico and northern Mexico, said Diego Medina, the historic preservation officer for the Piro-Manso-Tiwa tribe. “Tribal communities have existed within that stretch of land between the Salinas Basin and the gypsum mounds of White Sands in central New Mexico for thousands of years,” he told me.

It’s a chronicle that Medina painted recently in a mural entitled “long has the light wandered to lay itself upon you.”The 23,000-year-old fossilized footprints uncovered at White Sands National Park, 60 miles from the Trinity test, are depicted on one side; on the other, there is an endless trail of ancestors.

‘Hard on the heart’

In the film, security wire is unrolled into fences, a 100-foot steel tower rises up against the parched summer ground and the world’s first nuclear weapon is assembled. Later, after a monsoon nearly derails the test, and the bomb is just about to detonate, Oppenheimer says, “Lord, these affairs are hard on the heart.”

Then comes the blast, near silence and the sound of Oppenheimer’s labored breathing. Many interminable seconds later, the shock wave hits like a riptide. But we are largely only shown the impact on Oppie — first his elation, then ambivalence and later, after Little Boy and Fat Man are dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, guilt. He realizes that arms control is needed and so begins another chapter of his career and eventual public downfall.

There is nothing to suggest during any of that storytelling that New Mexico was essentially poisoned, its residents never warned, evacuated or educated about the health hazards of the July 16, 1945 Trinity test.

“It was,” as artist Medina put it, “a great act of desecration.”

Some geologists propose that this moment marks the start of a new epoch of geologic time, the Anthropocene. In New Mexico, it marks a new epoch of our own — when we became a nuclear colony. We are the only “cradle-to-grave” state in the nation, home to uranium mining, nuclear weapon manufacturing and waste storage. Two of the nation’s three weapons labs — Los Alamos and Sandia — are located here, and some 2,500 warheads are buried in an underground munitions complex spitting distance from the Albuquerque Sunport.

Los Alamos National Laboratory is currently undergoing a multi-billion-dollar expansion to create plutonium pits on an industrial scale — the “new Manhattan Project,” as Ted Wyka, the National Nuclear Security Administration’s field office manager, recently said in an aside before a media tour. Wyka told me he imagined himself in the role of Lt. Gen. Leslie Groves, the director of the Manhattan Project; LANL’s current director Thomas Mason was his Oppenheimer, he said.

The film gestures obliquely toward a future world irrevocably changed by the spectacle of nuclear military might. That future — our present — is now a global arms race.

Los Alamos, 80 years later, is a full-fledged city, “a model community” and an “atomic utopia for Postwar America,” as one history reads. The release of the film has only primed the town for the onscreen rehabilitation of its paterfamilias.

One can see the Oppie mania inside the lab, too, where Oppenheimer photomontages are emblazoned across the walls of LANL’s badge office, its new Employee Training center and a corridor in Technical Area 55 that leads to where plutonium cores are hewn. At a city park, Oppenheimer and Groves have been memorialized in bronze, a paean that might survive a nuclear winter, should the worst come to pass.

Trinity Drive, just down the road, was one of the first streets to be named in Los Alamos. Other thoroughfares are named for local tribes: Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Jemez, Tesuque, Nambe, Navajo (not to mention Enewetak and Bikini atolls) — as if having a street named after them could undo the damage the weapons complex wrought on Native lands.

“You question, why are they up there in our sacred mountains? Why can’t we go fishing up there anymore? Why can’t we collect our pottery clay there anymore?” said elder Kathy Wan Povi Sanchez of San Ildefonso Pueblo, thinking back to when she was young. “The secrecy of the atomic bomb creation also kept a lot of our people in harm’s way because [the lab] wouldn’t tell us when the experiments were being detonated,” she continued, recalling how explosives were tested in surrounding canyons. “They didn’t want people to know what they were doing.”

It wasn’t until the late 1940s or so that “the Pueblos realized that this thing at Los Alamos was a permanent incursion into their world,” said Dmitri Brown, a Tewa scholar who writes about the history of the Manhattan Project and whose great-grandfather worked as a carpenter at the secret lab.

The Pajarito Plateau, a constellation of sites that includes Tsankawi and Tsire-eh among many others, is still considered an ancestral home, Brown continued. “This is a place where you came from. This is a place where you can go back to and feel and see and breathe what your ancestors felt and saw and breathed.”

And yet, in the film, there are only two references to Indigenous peoples. In the first, Oppenheimer is selecting the Pajarito Plateau for the Manhattan Project. The second arrives after the U.S. decimates Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A scene in the oval office shows a crass Harry Truman asking Oppenheimer what to do with the site now that the bombs have been dropped.

Oppenheimer’s response? “Give it back to the Indians.”

Instead, the nuclear arms race was born. Los Alamos grew from 200 to 12,000 in a matter of a decade. Today, it’s 70 percent white, has the nation’s highest percentage of PhDs per capita, and is among the wealthiest cities in America. This most rarefied place stands in stark contrast to its surrounding Indigenous and Hispano communities, some of whose residents still work in some of the most dangerous jobs at the lab.

“They don’t talk about how New Mexicans did the dirtiest jobs, how we were part of building the roads and the bridges and the buildings. And then, when that was completed, they sent us into the dirtiest jobs inside of the labs handling radioactive waste,” Tina Cordova said in a panel discussion after a showing of the film at the Center for Contemporary Arts in Santa Fe.

“They also didn’t depict the women that they bused up there, Native women and the Hispanic women that literally cooked every meal, cleaned every house, changed every diaper, and made every baby bottle.”

What remains is a persistent belief that the creation of atomic weapons ended World War II and made for “one of the greatest scientific achievements of all time,” as a plaque near the Santa Fe Plaza reads.

No reckoning

There is no rule that says cinema must be accurate. “All art is useless,” Oscar Wilde once proclaimed. Its purpose, he said, is not to “instruct or influence.”

But “Oppenheimer” does, in fact, have the power to influence. For better or worse, this blockbuster has already been seen by millions of people around the globe, many of whom knew little or nothing about the history of the atomic bomb. The film, widely hailed as brilliant and thought-provoking, is perhaps the one and only time they’ll be exposed to the story. With just a few seconds of added footage, the movie could have given some context. It could have filled in the blind spot and acknowledged the people who lost their lives or lost family members. But the reckoning never came.

Oppenheimer bound us to the bomb. His story is our story — the tale of a borderland that became a tourist mecca that became the nerve center of the Atomic Age.

At the movie’s crescendo, the Trinity detonation, I heard women in the theater sobbing.

Gutierrez, White and Cordova, all three on the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium’s steering committee, left the film no less resolved. Days after seeing the movie, Gutierrez was back at work, researching all the infants that died the summer of the Trinity test. Cordova was busy writing about the movie and pushing for compensation for New Mexico’s downwinders, her mission for the past 18 years. And White had helped organize a photography exhibition in Las Cruces on the legacy of Trinity from a local perspective.

The movie’s over, but the battle goes on.

…

Searchlight New Mexico is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that seeks to empower New Mexicans to demand honest and effective public policy.”

An important story on the impact of the nuclear age on the people of New Mexico. Thank you