Notes from the Sadlowski Campaign for USWA President in 1976-77Part 2 – David v. Goliath in the USWA

By Garrett Brown

This is the 2nd in a three-part Stansbury Forum posting on Steelworkers Fightback (SFB), a reform movement within the United Steelworkers Union in the 1970’s. Garrett Brown documents the issues and personalities that drove that movement. The series is of great relevance today and can help inform our understanding and appreciation of the reform movements underway in many large US unions. The International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) has new leadership as does the United Auto Workers (UAW). In the United Food and Commercial Workers union (UFCW), America’s largest retail union, there is an active opposition called Essential Workers for Democracy. They had a big presence at the union’s most recent convention in April and are actively pointing toward the 2028 convention.

Peter Olney, co-editor of the Stansbury Forum

Part 2 – David v. Goliath in the USWA

Since the Steelworkers union’s founding in 1942, there had been three top officers – President, Vice-President and Secretary-Treasurer – as well as a National Director for Canada and 24 District Directors, who together made up the union’s policy-setting International Executive Board (IEB). Despite a Black membership of about 25%, there had never been an African-American international officer and there were only a handful of Black international staff representatives or employees at the union’s Pittsburgh headquarters.

At the 1970 USWA convention, delegates rejected a proposal from the union’s internal civil rights “National Ad Hoc Committee” to increase the number of vice-presidents by two, or add three more national directors, as a means of adding Black and Latino representation to the IEB. As the SFB campaign began to take shape, with significant support from Black and Latino steelworkers, the Official Family reshuffled the international officers to create a group of five – President, Secretary, Treasurer, Vice President for Administration, and Vice President for Human Affairs. The VP for Human Affairs was tacitly designated for an African-American officer.

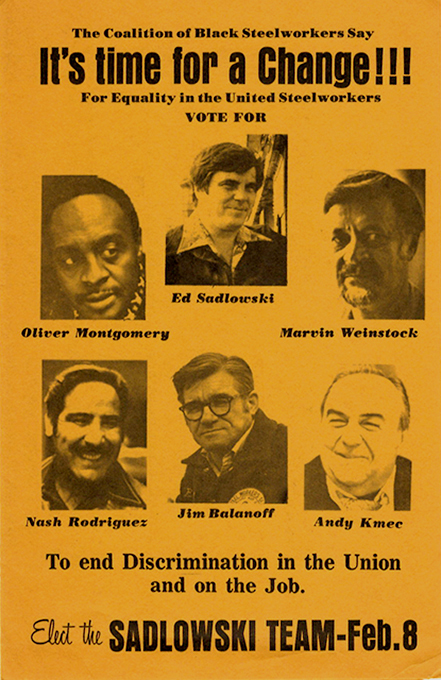

Based on the success of Sadlowski and others in District 31, the effort for a new kind of unionism in steel went national in the February 1977 election. The SFB slate for international union officers were candidates who had spent years working on the factory floor before becoming local union officers and then international staff, and who had distinguished themselves from other union officials by their support of democratic and militant unionism.

The slate was headed by Sadlowski as the presidential candidate. The Treasurer candidate was Andrew Kmec, an oil worker and steelworker at US Steel before joining the USWA staff where he organized the independent union for the 600 international staff representatives. The Secretary candidate was Ignacio “Nash” Rodriguez, with 27 years experience as a copper miner in Arizona and later worker at American Can in Los Angeles. The Vice President for Administration candidate was Marvin Weinstock of Youngstown, OH, who worked 28 years in steel mills before becoming an international staffer, and who was a member/supporter of the Socialist Workers Party in his younger days. The Vice President for Human Affairs was Oliver Montgomery, who worked in steel for 20 years before joining the union contract research department. Montgomery, an African America, was a leader of the National Ad Hoc Civil Rights organization within the USWA, as well as a leader in the national Coalition of Black Trade Unionists.

Lloyd McBride, District 34 Director in St. Louis, was the Official Family’s candidate, with the blessing of outgoing president I.W. Abel. The McBride slate included three other District Directors – Frank McGee, Joseph Odorcich, and Lynn Williams of Canada, as well as an African American, Leon Lynch (to match Oliver Montgomery on the SFB slate).

At the end of August 1976, the USWA held its convention of 4,000 delegates in Las Vegas. The convention delegates were overwhelmingly members and supporters of the Official Family, so it was no surprise that the motions from District 31 delegates to end the ENA, to establish membership ratification for basic steel contracts, and to roll back individual member dues and the high salaries of district and national union officers all failed. The convention highlighted the main themes of the SFB campaign and showed that the SFB candidates were not intimidated or afraid of the Official Family. Ten days after the convention, Sadlowski officially announced his slate’s campaign for international officers.

The SFB program was defined not so much by written materials – although those were generated and distributed as widely as there were volunteers to hand them out – but even more by the speeches and interviews of Sadlowski and slate members on a very wide range of issues, not just the standard “bread and butter” contract items like wages, pensions, speed-ups, layoffs, and grievance procedures. SFB events around the country were characterized by short initial presentations and then lengthy – often 1 to 2 hours – question and answer segments where hundreds of steelworkers got their say and got to hear what the SFB stood for.

The overall themes of union democracy and militant defense of the union membership were fleshed out in discussions of the right to strike, the right to ratify contracts, racism in the mills and in the union, women workers’ rights on the job and in the union hall, safety and health, pollution control, the salaries and perks of the union bureaucracy, the needs of small plants and their union locals, and national politics like an independent labor party and opposition to wars like the Vietnam war, which had just ended.

Sadlowski and his running mates framed their remarks as part of American working class history and the decades of efforts by native and foreign-born workers to defend their rights and improve their lives through member-controlled unions. The SFB program was one of the social movement unionism of the 1930s rather than the employer-centered business unionism of the Official Family.

Abel and the Official Family took particular offense to Sadlowsi’s mocking of them as “tuxedo unionists,” based on their high salaries. As USWA president, Abel received $75,000 annually, and District Director pay was raised from $25,000 to $35,000 at the August 1976 union convention, while the average steelworker was earning $17,000 a year.

Sadlowski was the real deal in terms of working class leaders. He was a third generation steelworker from an working class neighborhood in an industrial city. He studied labor history on his own, and was conversant in the trials and tribulations of the previous century’s worth of efforts by workers to establish unions and improve their communities. He also reveled in working class culture, such as the songs of the Industrial Workers of the World (Wobblies). Despite growing up in an insular community, and without using explicitly Marxist language, Sadlowski explained the world in class terms, from the point of view of the working class and its role in society.

This was one of the reasons that he was a very effective speaker in front of steelworkers and other workers. At the SFB campaign rallies, Sadlowski was in his element and relished the opportunity to spend literally hours answering questions and connecting his proposals to those of previous generations of unionists. At campaign events, Sadlowski was able to make a genuine connection with not only “white, male ethnic” steelworkers, but also Black and Latino workers as well.

Other members of the SFB slate were also excellent speakers and perhaps more disciplined – particularly Oliver Montgomery. Steve Early, a SFB volunteer in the Pittsburgh area, remembers Montgomery as “by far, the most fiery, articulate, and focused speaker on the SFB slate, almost Malcolm X like on the stump, due to his mix of personal cool, furious disdain, and scathing mockery of the ‘Official Family’ and its steel industry friends.”

In South Chicago, the SFB campaign was an endless whirlwind of events. These included regular leafleting, often pre-dawn, at the gates of the numerous steel mills, fabrication shops, can factories, and other USWA-represented workplaces. Rallies were held at USWA local union halls, including at US Steel South Works, Republic Steel, and Inland Steel. When the other members of the SFB slate came through town, I would usually sit down with them for interviews that would make their way into The Daily Calumet. There were grassroots fundraising events like the weekly mostaccioli pasta dinners on the East Side, numerous sales of raffle tickets for prizes, or the weekly bingo games sponsored the USWA local at Danley Machine on Chicago’s West Side. In December 1976, Sadlowski held a three-day holiday party at his home to allow for the greatest number of steelworkers to come by.

On a national level, similar activities were happening in the steel centers around the country: Pittsburgh, Youngstown, Bethlehem, Cleveland, Detroit, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Houston, St. Louis, Milwaukee, Bridgeport, CT, and Pueblo, CO. In Canada, a major rally was held with the SFB slate at USWA Local 6500 representing 15,000 nickel miners at Inco in Sudbury, Ontario. Rallies with one or more of the candidates frequently drew large audiences, often preceded by plant-gate leafleting, and generated an enthusiastic response. In areas where the SFB had few contacts, particularly in the South and Southwest, campaign headquarters in Chicago formed traveling teams of steelworkers and volunteers who used their vacation time to leaflet plant gates and make house calls with potential supporters.

On a local level, SFB committees generally consisted of individual steelworkers inspired by the campaign, and members of various leftwing organizations. SFB supporters included members of the Communist Party, Socialist Workers Party, International Socialists, and Revolutionary Communist Party, among others. Several organizations, including the Spartacist League and October League, opposed the SFB campaign as nothing more than an internal faction fight between union bureaucrats.

Radicals of the various tendencies played an important role as committed activists for the SFB campaign at plant gates, house meetings, fundraising, rallies, and outreach. Depending on the organization and individual members, radicals were effective campaigners to the degree that they prioritized broadening support for the SFB campaign message of union democracy and militancy, rather than promotion of their own organization.

Meanwhile, the McBride campaign, the Official Family, and USWA HQ were pulling out all the stops to prevent a SFB victory.

The 600 international staff representatives – only a handful endorsed Sadlowski – were coerced into making financial contributions to the McBride campaign to stay in the good graces of their supervisors. The staff spread throughout the US and Canada used their critical role at the local union level – handling grievances and contract negotiations, especially in small shops and locals – to pressure local union officers and members to support McBride. The staff conducted open electioneering for the Official Family slate at local union meetings and other gatherings.

The McBride campaign enjoyed full use of the union’s resources, including union facilities and staff time by the union’s lawyers and public relations personnel. The national union magazine, Steel Labor, campaigned so openly for McBride that late in the campaign a judge approved a settlement in a SFB lawsuit which required the magazine editors to provide SFB with the intended copy before it was published so that the SFB could object and propose alternatives to the text.

One huge advantage for McBride was that the union illegally denied SFB a complete membership roll, their contact information, and the location and officers of the union’s 5,400 local unions until late in the campaign period. This was only partially overcome when the SFB lawsuit settlement required one pre-election mailing to the entire USWA membership with SFB literature.

At the same time outside union officials – like the AFL-CIO’s George Meany and Lane Kirkland, among others – contributed resources and endorsements to McBride while denouncing Sadlowski and his slate.

The steel industry also got involved in the campaign, putting its thumb on the scale for McBride. J. Bruce Johnson from US Steel, and the lead industry negotiator in contract talks, gave interviews indicating overturning the ENA no-strike agreement (which Sadlowski opposed) would lead to “chaos” in the industry. At a local level, supervisors harassed SFB supporters on the shop floor in an attempt to intimidate steelworkers, and at US Steel Gary Works steelworkers leafleting the plant gate for Sadlowski were arrested by police called by the company (no charges were ultimately filed).

Using the media resources of the union, the McBride campaign were able to generate ongoing stories in its favor from the country’s labor beat reporters (anxious to maintain their sources at the USWA), from newspaper editorial writers, and from conservative columnists like nationally-syndicated “Evans and Novak.” One exception to the rule was a column written in January 1977 by famed “labor priest” Msgr. Charles Owen Rice in the Pittsburgh Catholic, which supported Sadlowski and noted “workers like him and so do those who are not workers – students, writers, reformed, and idealists of all sorts. The man inspires loyalty as well as affection and thus represents a formidable threat to the old guard.”

The McBride campaign pounded away in the media with their key talking points about the SFB campaign: that it was a “threat to the union and members’ livelihoods;” that the slate was inexperienced and incompetent; that a SFB presidency would bring the “chaos and collapse” the Miners for Democracy leaders supposedly brought to the UMWA; and that the SFB campaign was controlled by “outsiders“ (wealthy liberals, communists, and employers).

Some of this media campaign and adverse coverage had an impact on Sadowski’s image and raised questions for some steelworkers. For example, Penthouse magazine published a long interview with Sadlowski where he noted that some mill jobs (like those working on coke ovens) were too poisonous and dangerous to be safely done by anyone, and he waxed poetic about how he would rather see steelworkers be doctors than industrial workers. The McBride campaign spun the interview as an indication that Sadlowski wanted to eliminate steel jobs, and that he was belittling steelworkers and their contribution to American society.

In the final weeks of the campaign, it was the “outsiders” charge that got the most media attention. The SFB pushed back, pointing out all of the outside support that the McBride campaign had received directly and indirectly from non-USWA union officials, media, and steel industry, as well as the coerced donations and misuse of resources internally. But on January 9, 1977, SFB felt compelled to release information on its fundraising, which provided grist for yet another round of stories in the media.

The SFB records indicated that of the $150,000 raised ($795,000 in 2023 dollars), 80% of it came from steelworkers ($120,000) with $26,000 coming from non-USWA donors. None of these were employer donations, but rather $100 to $500 contributions from a spectrum of wealthy liberals, Democratic politicians, academics, labor attorneys, and cultural figures like author Studs Terkel ($800 donation). The largest contributor was Frank Fried at $4,000 ($21,200 in 2023 dollars).

Fried, was a successful music impresario who ran the tours of well-known folk and rock music bands from the 1960s onwards. Fried, who had been a member/supporter of the Socialist Workers Party in the 1940s and 1950s, never lost his pro-worker and pro-union beliefs and was proud to share his “ill-gotten gains” from the music world to support efforts for a democratic and militant union. Fried was the kind of guy who had been “around the block once or twice” and played a key role in the non-USWA fundraising activities designed to counterbalance the McBride’s dunning of the USWA staff and financial support from officials from other unions.

The Election

“No one will ever know for certain whether the election was stolen from Sadlowski, but there is enough evidence to raise serious questions.”

Given the unequal resources available to the opposing campaigns, the official results were not a surprise. In April 1977, the USWA International Tellers reported that McBride received 328,861 votes (57%) to Sadlowski’s 249,281 votes (43%), with McBride having an 80,000 vote margin. Sadlowski won a majority of the members in basic steel locals, a majority in two of the three Pittsburgh-area districts, a majority in locals with more than 1,000 members, and a majority in 10 of the union’s 25 Districts.

But there were enough reports of fraud that Sadlowski filed a series of appeals and lawsuits that went on for almost a year following the February 8, 1977 election. On February 18th, Sadlowski filed an internal challenge within the 10-day limit set by the union (before all reports had been received from the field) for both pre-election misuse of union resources and election day fraud. The union’s International Executive Board rejected the challenge in May 1977. Sadlowski then filed a complaint with the U.S. Labor Department on June 17, 1977. After four extensions to receive a report from the Canadian Labor Department’s investigator (who was a contract lawyer working for the USWA in Canada), the Labor Department rejected Sadlowski’s challenge in November 1977. Sadowski’s attorney Joseph Rauh then filed a suit in U.S. District Court in Washington, DC, to overturn the election and order a new one, but the suit failed.

No one will ever know for certain whether the election was stolen from Sadlowski, but there is enough evidence to raise serious questions. The Labor Department investigation discounted thousands of McBride’s votes, and the Canadian results were suspicious, not to mention all the pre-election misuse of union resources, refusal to provide membership rolls and local union locations, and extensive outside support to McBride.

Sadlowski had majority support in the basic steel locals, but these represented only 25% of the USWA membership. Sadlowski won the majority of locals with more than a 1,000 members, but there were only 192 locals of that size in the union’s 5,400 local unions. Seventy-five percent of locals had less than 250 members, which were dependent on the international staff for their basic functioning, and SFB won the majority in only 38% of these locals. Overall, SFB had poll watchers in only about 800 of the union’s 5,400 locals.

Joseph Rauh, Sadlowski’s veteran labor lawyer in Washington, pointed out that Labor Secretaries in Democratic Party administrations have almost invariably favored the officialdom of America’s labor unions, the incumbent decision-makers who decide where future campaign contributions and logistical support will go. Hence a favorable decision for Sadlowski in the election challenge was always a long shot, although that was a key part of the SFB strategy, and especially with the limited investigation conducted by the Labor Department. In the 1974 re-run of the District 31 race, the Labor Department had 200 election observers in the Chicago-Gary, Indiana district alone, but in February 1977, the Labor Department dispatched only two observers per district, for a total of less than 50 for the entire United States

Fraud

Nonetheless, the November 1977 Labor Department findings discounted more than 17,000 votes that had been credited to McBride. This represented almost 25% of McBride’s 80,000 vote margin, and was 40% of McBride’s margin in the United States. The report also confirmed instances of fraud that Sadlowski had documented in the February 1977 internal challenge and later complaints to the Labor Department and federal courts. This evidence included prohibited electioneering by staff and local union officials; locals that held no election but reported landslide results for McBride; lack of secret ballots in some locals; and vote totals which showed more McBride votes than there were members in the local. In Districts 36 and 37 in the Deep South, there were 150 local unions which reported zero votes for Sadlowski, not even one by accident.

The Labor Department refused to order a new election because the 17,000 discounted votes did not exceed 80,000 – McBride’s overall margin in the US and Canada – and the Labor Department also declined to conduct any additional investigation of the voting.

Canada, of course, is not subject to U.S. labor law, and was home to 163,000 USWA members in 900 local unions. During the campaign, former USWA president David McDonald (president from 1952 to 1965) told the news media: “Sadlowski will have to win the U.S. by a large margin because they will steal it from him up in Canada. I know, I stole four elections up there myself.”

The Canadian Labor Department responded to Sadlowski’s challenge to the election results there by contracting a local lawyer to investigate who was regularly employed by the USWA in local union grievance hearings, and whose future business dependent on the incumbent administration. McBride’s victory margin in Canada was almost 40,000 votes – half of his entire election margin in both countries. The Canadian investigator reported no irregularities that would require a new election, despite instances like District 5 in Quebec where there were 70 local unions without a single vote for Sadlowski. In District 5, McBride’s district-wide margin was 22,000 votes (24,655 votes to SFB’s 2,769), and Sadlowski officially received only 10.1% of the vote in the district while he registered 31% and 37% of the vote in the two other Canadian districts.

So it is possible that Sadlowski – if he had been able to obtain a second, supervised election as occurred with his 1973-74 elections for District 31 Director – could have won the USWA presidency.

Next: Part 3 – Strengths and Weakness of Steelworkers Fight Back

…