Learning and Building on the past: Notes from the Sadlowski Campaign for USWA President in 1976-77

By Garrett Brown

This is the first in a three-part Stansbury Forum posting on Steelworkers Fightback (SFB), a reform movement within the United Steelworkers Union in the 1970’s. Garrett Brown documents the issues and personalities that drove that movement. The series is of great relevance today and can help inform our understanding and appreciation of the reform movements underway in many large US unions. The International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) has new leadership as does the United Auto Workers (UAW). In the United Food and Commercial Workers union (UFCW), America’s largest retail union, there is an active opposition called Essential Workers for Democracy. They had a big presence at the union’s most recent convention in April and are actively pointing toward the 2028 convention.

Peter Olney, co-editor of the Stansbury Forum

.

Introduction

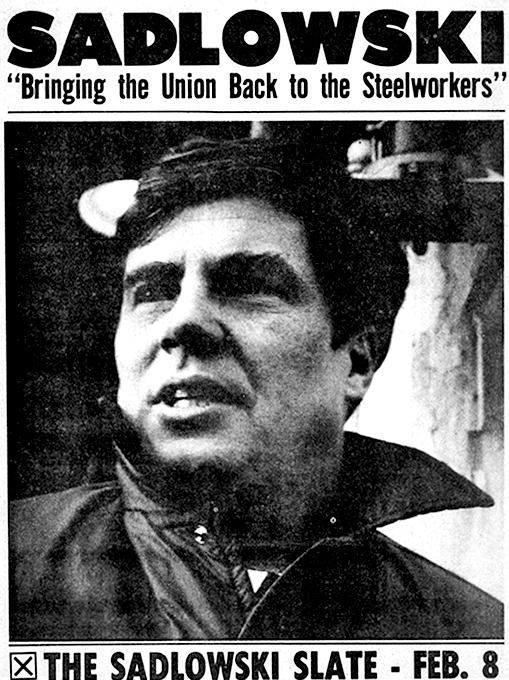

In 1976, I was a member of the Socialist Workers Party wroting articles for the party’s weekly newspaper, The Militant, under the pen name of “Michael Gillespie.”. I was also the labor reporter for The Daily Calumet newspaper in southeast Chicago, in the heart of the Chicago-Gary steelmaking industry where almost 130,000 steelworkers formed a key part of the national economy and were the largest district of the United Steel Workers of America (USWA) union. I covered the numerous local unions of the USWA, which then had 1.4 million members in the Chicago-Gary region. The biggest story during my days at the newspaper was the election campaign of Ed Sadlowski and the Steelworker Fight Back (SFB) slate for international officers of the USWA leading up to the February 1977 election.

The significance of the Steelworkers Fight Back campaign was that it was part of a wave of efforts by rank-and-file union members to fight for union democracy, and to remake their unions into more militant defenders of the rights and needs of their members, including not only economic issues but also addressing historic discrimination against Black, Latino, and women steelworkers. This effort continues today – almost 50 years later – as a new generation of working class leaders seek to organize new unions in their workplaces and to reshape their existing unions as democratic and militant organizations that can defend them on the job.

Part 1 – The right moment and the right campaign

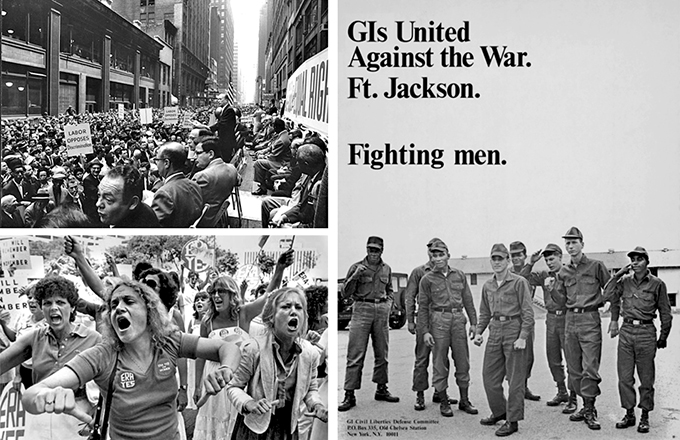

Upper Left: Charles Zimmerman speaks at a civil rights rally in the New York Garment District on 38th Street near 7th Avenue in New York City. Signs include “Labor Opposes Discrimination” May 17, 1960 Creative Commons/Kheel Center | Lower Left: Women demonstrate in favor of ERA. Tallahassee, Florida around 1979. State Library and Archives of Florida. | Right: Poster: GIs united against the war, Ft. Jackson. 1069. Library of Congress

The impact of the 1977 USWA presidential election campaign was generated by “the moment” in which it occurred. This moment included the previous decade of widespread social activism for civil rights, an end to the war in Vietnam, women’s rights, protection of the environment, and what was then called gay liberation. These social change ideas and movements had the biggest impact on young people, but also affected growing numbers of older working-class people, including steelworkers. Older workers may not have signed on to the full agenda of their children’s radical proposals, but many were more open (while some were not) to considering reforms to the “way it has always been.” The Watergate scandal culminating in Nixon’s August 1974 resignation called into question many elected institutions in the U.S. society as well.

At the same time the “social contract” in American society that existed between employers and unions between the end of the Second World War in 1945 and the bankruptcy of New York City in 1975 – in which unions were guaranteed modest improvements in wages and benefits in exchange for support for American capitalism and the U.S. government’s economic, political, and military exploitation of the rest of the world – broke down.

Even the more-protected sector of American workers (white men with unions) began to be subjected to what became known as the neo-liberal austerity regime, as maximizing the profits for corporate shareholders became the central and overriding concern of management. This meant increased wages and benefits first slowed, and then employers sought cuts; intensified productivity drives to increase output; cutting costs for protecting worker health and the environment; and squeezing the last penny of profits from operations by reducing re-investments in facilities, equipment, and preventive maintenance.

The unions’ leaderships – epitomized by the USWA – were completely unprepared and without alternative proposals when employers simply tore up the 30-year-old social contract and began dictating the terms of their newly intensified profit-maximizing regime. The pro-business unionists’ response was to seek even closer collaboration and partnerships with management – such as the management-union Experimental Negotiating Agreement (ENA) which banned strikes and required mandatory arbitration of contract issues, joint lobbying for tariffs on foreign steel, and other campaigns to raise industry profits.

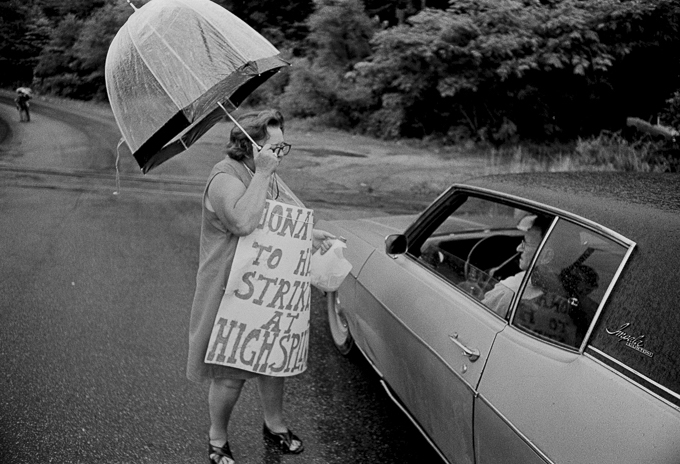

Steelworkers, like other union workers, faced worsening conditions on the job including compulsory over-time, relentless employer “productivity” programs, health and safety hazards generating immediate injuries and long-term diseases, unfair disciplines and dysfunctional grievance procedures. Moreover, the persistent racial discrimination in the mills and lack of representation in the union generated an ad hoc civil rights movement in the industry and union. Women, who were coming into the mills in greater numbers, also faced discrimination and often intense levels of harassment and assault.

This combination of factors sparked worker actions on the job, and efforts to recast their unions with greater internal democracy and militancy toward their employers. The period between 1965 and 1975 witnessed a strike wave greater than any other period after World War II, and on par with the great strike years of 1919, 1937, and 1947. There were an average of 350 “major strikes” (involving more than 1,000 workers) per year in the 1965-75 period, and some 5,000 “non-major strikes.” About 30% of the strikes were “wildcat” strikes – unofficial work stoppages organized by the workers and not sanctioned by union officials. The high point of the strike wave was 1970 when workers struck General Motors, General Electric, the railroads, and two major wildcat strikes of postal workers in New York City and Teamster union truck drivers.

The worker response to worsening conditions was reflected in their unions as well. In 1969, members of the United Mine Workers union began an effort to oust W.A. “Tony” Boyle, a corrupt and violent president, resulting in the election of the Miners for Democracy (MFD) slate in December 1972. In 1973, Sadlowski and his supporters launched their campaign to first change District 31, with plans in mind for a national change in the 1977 USWA presidential election. In 1976, members of the Teamsters union founded Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU), which led heroic efforts to reform the mobbed-up, Jimmy Hoffa-led union until a reform candidate won the presidency in 1991.

The SFB election campaign was an example of “the right campaign” meeting “the right moment” with national implications for the labor movement. The campaign’s central themes of union democracy and union militancy were reflected in the slate of candidates, the program and position on critical issues, and the response of the steelworkers who joined and promoted the effort. Its significance was also seen in the extensive media coverage in national and local newspapers, national magazines, and television reporting (including formal candidate debates on a local Chicago station, national NBC’s “Meet the Press,” and the syndicated Tom Synder show).

The face of the campaign was Edward Sadlowski, born and raised in South Chicago and a third-generation steelworker. His father, also Edward but known as “Load,” had helped organize the USWA at Inland Steel in the 1930s, and Eddie’s grandfather had come over from Poland at the end of the 19th century to work in the mills. Eddie grew up fascinated by labor history, and he had a real interest in learning about not only the events and leaders of the union movement, but also the songs, stories, and culture of the multinational American working class’ efforts to organize, defend itself, and improve their lives over the course of the previous century.

In 1956, Sadlowski started as a 18-year-old machinist apprentice at US Steel South Works. He was not a much of a machinist, so he was given an oil can and told to lubricate cranes and other equipment throughout the plant. Thus was born “Oil Can Eddie” – a nickname that Sadlowski did not care for as it represented a demotion from his machinist apprenticeship – but it meant that Eddie spent his days at work talking to dozens of co-workers throughout the mill.

In 1960, Sadlowski was elected shop steward, and in 1962 was elected to the union grievance committee. In 1964, at the age of 25, Sadlowski became the youngest local union president at Local 65, representing the then 14,000 workers at the mill. Eddie was re-elected as Local 65 president in 1967. In 1970, Sadlowski was appointed as an international staff representative, one of 60 staff men in District 31 servicing the district’s 295 local unions.

In 1972, Joseph Germano, who had been District 31 Director since 1940, was required to retire by the USWA constitution. In his eight terms as district director, Germano had only faced one election challenger, and Germano had hand-picked Samuel Evett to succeed him. Evett had become a union staffer in 1936 and was Germano’s assistant director for the 32 years since 1940.

The USWA had always been a top-down organization, from the time the United Mine Workers union chief John L. Lewis assigned Phillip Murray to run the Steel Workers Organizing Committee in the 1936. Murray was USWA’s founding president from 1942 until his death in 1952 and ran a highly centralized organization. In 1973, the USWA’s international union President I.W. Abel, its Vice President and Secretary-Treasurer all ran unopposed for re-election, as did 14 of the 25 district directors. The USWA had an almost feudal dynasty feel from the Pittsburgh headquarters through the 25 districts to the 5,400 local unions.

Sadlowski decided to challenge the “Official Family” tradition of hand-picked successors, and run on a campaign of union democracy, union militancy and “social movement” unionism versus the “business unionism” represented by Evett and the union leadership in Pittsburgh.

Sadlowski announced the 1972-73 campaign for District 31 Director stating:

“I consider democracy within the union to be the most important single issue. If the steelworkers had been consulted, they never would have agreed to an International Executive Board which excluded Blacks, Latinos and women. If the steelworkers were consulted, they would insist on their right to vote on union contracts in the same manner that other unions do. They rightfully feel they are not running their own affairs and they are not being represented on the district level.”

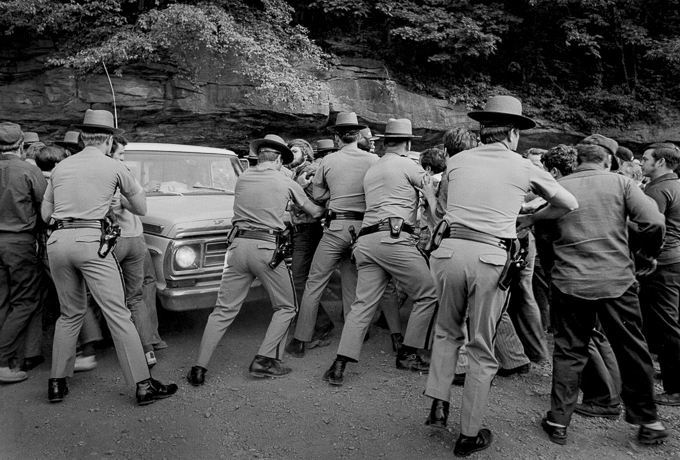

The election was held on February 13, 1973, and at midnight Sadlowski was leading Evett by about 3,500 votes. The vote counting was halted, and when it resumed the following day, Evett was declared the winner by a margin of 2,350 votes.

Sadlowski protested the election results, and a U.S. Department of Labor investigation found that there had been massive fraud in the election – including ballot box stuffing in Local 1014 at US Steel Gary Works – as well as misuse of union funds, and improper electioneering by international staff. A Federal court battle ensued, and in July 1974, Evett and the Pittsburgh headquarters agreed to a settlement, under pressure, for another election to be conducted by the Labor Department.

In the November 1974 re-run election, the member turn-out increased by 25% over the February 1973 vote, and Sadlowski won the re-run by 20,000 votes and a margin of 2 to 1. Sadlowski took office as District 31 Director in direct opposition to most policies of the union hierarchy and despite their best efforts to defeat him. With the centralization of power in the USWA, almost all of the reforms Sadlowski proposed during the District 31 campaign could be achieved only with a new leadership in Pittsburgh. Planning for the presidential campaign began in the wake of the 1973-74 district campaign.

Between the 1974 district director and the 1977 presidential races, there were important local union elections, and the campaign to replace Sadowski as district director since he had to give up the regional post for the national election in 1977.

Local union officer elections in April 1976 had resulted in supporters of SFB being elected by large margins. At Local 65 at South Works, SFB supporter John Chico beat Frank Mirocha by almost two to one (2,228 to 1,304 votes) with a near record turnout of the local membership. Chico’s slate of candidates won eight of the 10 other offices up for election. Mirocha was personally backed by corrupt Chicago Alderman “Fast Eddie” Vrdolyak, who was successful in installing his candidate for president, Tony Roque, in the non-USWA, company-dominated union at Wisconsin Steel. Vrdolyak intervened in the 1977 elections as well – opposing Sadlowski and District 31 Director candidate Jim Balanoff.

In April 1976, at Inland Steel across the state line in Indiana, Jim Balanoff also won by nearly two to one (6,050 to 3,067) over Hank Lopez, and the SFB supporter slate took eight of the nine other offices. The vote at Inland was also near-record with 12,000 of the 18,000 members casting ballots. During this election, as was the case with Balanoff’s previous and subsequent election campaigns, The Daily Calumet played a minor role. In 1947, when Congress was passing the Taft-Hartley Act which greatly restricted the rights of unions, Balanoff sent a letter to the Daily Cal opposing the bill, which was published and which he signed as a member and local organizer of the South Chicago branch of the Communist Party. So at every union election, Balanoff’s opponents came by the Daily Cal office to make another copy of the letter from the paper’s archives.

After his Local 1010 victory in April, Balanoff became the SFB candidate for District 31 Director in the February 1977 election. In contrast to the Joe Germano days, the district director race drew 12 candidates, five of whom garnered enough local union nominations to appear on the ballot. One of those was John D. Carey, the sitting president of the Chicago Board of Education, who had been a USWA international staffer for 15 years and a local union president for 10 years before that. Balanoff won the district director election by nearly 6,000 votes over his nearest challenger (19,108 to Harry Piasecki’s 13,442). Four of the five candidates supported McBride, which likely increased McBride’s District 31 vote with local candidates campaigning on his behalf.

The basic strategy of the 1976-77 SFB campaign was to combine the District 31 campaigns (district director and local union presidents, 1973-76) with key features of the 1972 Miners for Democracy campaign, including high-profile media work, a legal strategy to engage the federal government against fraud, and outside fundraising to counterbalance the union officialdom’s resources. There was not a national network of USWA reform organizations in existence, and not enough time (summer 1976 to February 1977) to create a new representative network, let alone conduct the years-long, patient building of local grassroots organizations of reform-minded steelworkers. So the strategy focused in building a centralized campaign organization led by trusted Chicagoans, with some outside help, that would direct and coordinate campaign volunteers.

It was clear that the SFB campaign tapped into a deep reservoir of concerns among working steelworkers and interest in hearing about alternative approaches. The slate received 521 nominations from local unions – 140 nominations were required for ballot status – despite the refusal of the Pittsburgh headquarters to provide a complete list of the USWA’s local unions. Volunteer supporters set up campaign offices and conducted plant-gate leafleting, rallies, and fundraising events around the country. Campaign events for Sadlowski in Pittsburgh, Baltimore, and numerous other steel towns had higher attendance and much more enthusiasm than the Official Family events.

The potential impact of a successful SFB campaign on the labor movement and industrial relations in general was not lost on the many affected parties. Sadlowski was vociferously denounced by union officials including I.W. Abel, former AFL-CIO leader George Mean and his successor Lane Kirkland, and national teachers union president Albert Shanker, among others. Steel industry officials, including lead contract negotiator J. Bruce Johnson of US Steel, warned of “chaos” should Sadlowski become president. Newspapers like the Wall Street Journal, New York Times and Chicago Tribune all editorialized against a SFB victory. The newspapers’ labor reporters – anxious to maintain good relations with labor officialdom – routinely belittled SFB’s prospects, while also drawing a dark picture of a Sadlowski presidency.

At the same time, the SFB campaign became a pole of attraction not only for steelworkers wanting change in their union and mills, but also for rank and file members of other unions, and those seeking social change for people of color and women in society at large. Radicals, and liberals with money, were excited by, and contributed to, the latest labor battle of David versus Goliath.

Next: Part 2 – David v. Goliath in the USWA

…

I think I am related to Oil Can Edda…..gotta great grandpa….Anthony Sadlowski 1840-1910…And to boot I was member of USW local 3000…the maritime division….sailed OS on the SS Harry Coulby in 1973….and pulled into Interlake Steel more then once….would love to make contact with any Sadlowski…

Yours,

Ted Sadlowski

redtedfs@yahoo.com