The Teamsters’ UPS Strike of 1997: Building a New Labor Movement

By Rand Wilson and Matt Witt

The Forum revisits the August 1997 strike at UPS by republishing an article written by two former Teamster staffers. Rand Wilson and Matt Witt worked in the Communications Department at the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) and played major roles in helping members to build unity and wage a successful two week strike. Over 25 years later, what lessons can be learned as over 340,000 Teamster members at Big Brown are negotiating for a new agreement and preparing for a strike if necessary when the contract expires on July 31, 2023? – Peter B. Olney

.

At a time when the American labor movement is struggling to reverse its decline in membership and strength, the Teamsters’ nine-month contract campaign at United Parcel Service in 1997 demonstrated that labor can rebuild its power by involving its members, reaching out for public support, and challenging corporate power on behalf of all working people.

Twelve days into the two-week, nationwide United Parcel Service strike in August 1997, fifty workers at the RDS package delivery company in Cincinnati voted to join the Teamsters Union. The company tried to talk them out of it, asking why they would want to join an organization that had led 185,000 people out on the street with only $55 per week strike benefits. But even without knowing what the strike’s outcome would be, the RDS workers were attracted, not repelled, by the UPS Teamsters’ strong stand. “UPS workers came down in the mornings and afternoons and talked to us about why they were on strike and how they were fighting to stop the company from contracting out their work,” said RDS driver Daniel Jordan. “They showed that they were behind us, and we saw what we can do when we’re united” (The Teamster, October 1997).

Soon after the strike, workers ranging from retail department store employees in Orange County, California, to manufacturing workers and public employees in Pittsburgh began to call local unions in their areas, wanting information about organizing. In Washington State, 4,000 corrections officers who had an ineffective, unaffiliated association voted to become Teamsters. “A lot of us watched the UPS strike, and it gave us a major push toward the Teamsters,” said corrections officer Jim Paulino. In Ohio and in Canada, part-time, low-wage workers at McDonald’s were inspired to try to organize (The Teamster, March 1998; Vancouver Province, March 1998).

In all, the Teamsters Union had more organizing success in 1997 than in any year in recent memory, and the UPS victory inspired unorganized workers to contact many other unions as well (The Teamster Organizer, Spring 1998). “The UPS strike directly connected bargaining to organizing,” commented AFL-CIO President John Sweeney. “You could make a million house calls, run a thousand television commercials, stage a hundred straw- berry rallies, and still not come close to doing what the UPS strike did for organizing” (Sweeney, 1997, 8).

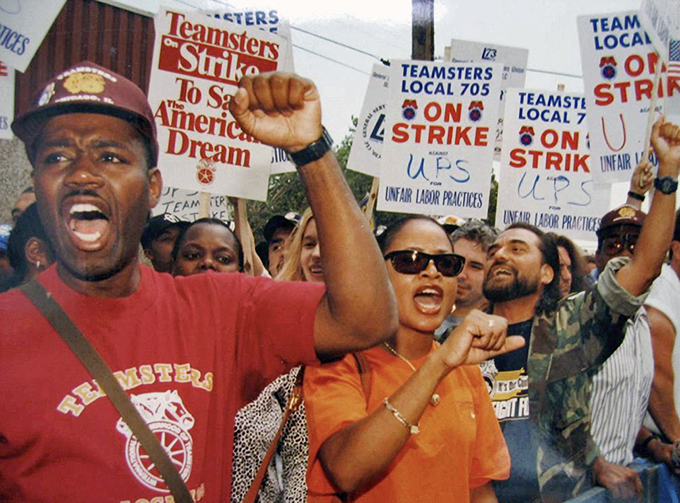

Far from scaring away workers from “irresponsible” unions, the Teamsters’ UPS victory drew the broadest public support the labor movement has enjoyed in years. Of the 185,000 UPS workers covered by Teamster representation, more than 184,000 took part in the strike. Thousands of members of other unions joined in the picketing and other events. Polls showed that the general public supported the strikers by more than two to one (Field, August 15, 1997; Greenhouse, August 17, 1997).

At a time when the labor movement is struggling to reverse its decline in membership, power, and relevance in American life, the nine-month UPS contract campaign that led up to the strike provided some valuable lessons. The campaign proved that working people will be attracted to a labor movement that is:

- a movement of workers, not just officials;

- a movement for all workers, not just its members; and

- a fighting force for working people, not just a bureaucratic service institution or a junior partner with management.

A Movement of Workers

Like most historic victories, the seeds of the rank-and-file contract campaign at UPS were planted many years before. In the 1970s, UPS workers began to organize in reform groups like UPSurge and Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) to challenge a union culture that discouraged membership participation and was based on backroom deals between top union officials and management (La Botz, 1990, 61).

Reformers argued that weak contracts and a failure to enforce members’ rights were a direct result of a lack of union democracy. A typical example was the shift at UPS to lower-wage, part-time jobs. The shift had started in 1962 under a deal between Jimmy Hoffa, Sr., and UPS to allow the company to use part-time workers. Then, in 1982, Hoffa’s old-guard successors agreed to freeze the starting part-time wage at $8 per hour (The Teamster, November/December 1996). By 1990, about half of all UPS workers were part-timers, with the percentage growing fast (Teamsters Research Department, June 1997, 3).

In 1991, Teamster members had their first chance in history to directly elect their top International Union leadership. The result was a victory for a reform slate headed by Ron Carey, a twelve-year UPS driver and longtime elected local union leader (Crowe, 1993). Despite unrelenting opposition from many old-guard local union officials who benefited from the traditional top-down culture, the reformers began to change “contract negotiations” conducted by union representatives and management into “contract campaigns” that involved members at every step. Like progressive leaders in other unions, Teamster reformers understood that the power of a huge multinational company like UPS cannot be challenged just by a few officials sitting at a negotiating table (Center for Labor Education, 1990; Service Employees, 1988).

The 1997 struggle for a new contract with UPS became a prime example of the new-style contract campaign. It was designed to overcome a management contract campaign that had several key strategic elements.

First, the company demanded givebacks, even though it was making more than a billion dollars per year in profits. UPS proposed shifting even more work to lower-wage part-timers. It wanted to expand subcontracting, which would reduce promotion opportunities for UPS workers. It offered lower wage increases than in the past, with no special raises to help close the pay gap between part-time and full-time workers (UPS Contract Proposals, March 27, 1997). Even if management’s demands didn’t prove successful, they would help the company in negotiations to counterbalance any worker proposals for improvements.

Second, the company expected to take advantage of divisions between reformers and old-guard local union officials. This strategy was based in part on management’s reading of a one-day national safety walkout at UPS called by reform leaders in February 1994, when the company unilaterally raised the package weight limit from 70 to 150 pounds. While the safety action forced the company to provide greater protection when handling the heavier packages, many old-guard local leaders urged their members not to walk out (Associated Press, February 8, 1994). The lesson management drew was that the top union leadership did not have the support of old-guard locals and could not call or win a national contract strike (Blackmon and Burkins, August 21, 1997).

Third, UPS sought to exploit the division in the work force between part-timers and full-timers. Management assumed that full-timers wouldn’t fight for more full-time opportunities and better pay for part-time workers, while the younger part-time work force wouldn’t fight for better pensions or reduced subcontracting of full-time jobs.

Fourth, UPS unilaterally launched a so-called “Team Concept” program two years before contract expiration in order to further divide worker from worker. Like many similar programs established by other employers, UPS’s Team Concept scheme used words like “cooperation” and “trust” to appeal to workers’ natural desire for peace on the job (Nissen, 1997; Parker and Slaughter, 1994; Wells, 1987; Witt, 1979). But the scheme’s fine print allowed the company to replace the seniority system with management favoritism and set up “team steering committees” that could change working conditions without negotiation with the union. Teams would take on some functions of supervision, pitting union members against each other over issues like job assignments and work loads (Teamsters UPS Update, November 1995; Walpole-Hofmeister, 1996).

For the union, the key to countering management’s strategy was to build membership unity (The Teamster, March/April 1997). Nine months before the contract was set to expire on July 31, 1997, the International Union sent a contract survey to all UPS Teamsters’ homes. The survey asked them not only to rank their priorities but also to mark activities in which they would participate in order to get a good contract: “Wear buttons or T-shirts,” “Pass out leaflets,” “Ask coworkers to sign petitions supporting our bargaining demands,” “Conduct parking lot meetings with coworkers,” “Phone bank members about contract issues,” and “Attend special UPS local union meetings” (1996 UPS Teamster Bargaining Survey; Greenhouse, August 25, 1997).

Local union officials, stewards, and rank-and-file activists were provided with leaflets and an eight-minute video, Make UPS Deliver, to help them use the survey as an organizing tool to talk to members about the importance of getting involved in the contract campaign.

In these materials, members and reform leaders emphasized the common interests of part-time and full-time workers. For example, part-time workers would benefit if full-timers’ pensions were improved because that would lead to more early retirements, which in turn would open up more full-time promotional opportunities for part-time workers. Meanwhile, said Teamsters Parcel Division Director Ken Hall in the video, “It’s important to full-time employees that part-time employees get their fair treatment in this contract because if they do, there’s going to be less incentive for UPS to continually erode full-time jobs and replace them with part-time jobs.”

To help organize membership involvement in the 206 Teamsters locals with UPS members, the International’s Education Department provided training on how to set up “member-to-member” communication networks. These networks made each steward or other volunteer responsible for staying in touch with approximately twenty workers—giving them information, answering their questions, and listening to their views (Countdown to the Contract, July 1996). The networks counteracted UPS management’s systematic communication system that provided frequent messages for supervisors to review with employees in “Pre-Work Communication Meetings.” Management’s messages typically were about competitiveness, productivity, and the need to avoid a strike or community outreach campaign by the union that would drive customers to other companies.

The International assigned nineteen field staff, including some rank- and-file UPS workers, to help locals set up their networks and get members involved. In cases where old-guard local officials refused to take part in the campaign, the field staff worked directly with rank-and-file activists and stewards to build membership unity (Moberg, 1997).

In the months before contract expiration, the networks were used by some locals to organize membership participation in a series of escalating actions that built unity among full-timers and part-timers:

- On the day before union and company negotiators exchanged proposals, Teamster members held worksite rallies in seven targeted cities. The next day, UPS negotiators complained that rallies like that had never been held so long before the contract expired. Their complaints encouraged Teamster leaders to double the number of rallies held before the next bargaining session two weeks later (Greenhouse, August 25, 1997).

- The union provided members with the tools to document the company’s record as one of the nation’s worst job safety violators (Drew, 1995). More than 5,000 members filled out special “EZ” safety and health grievance forms. The grievances became the centerpiece of local “Don’t Break Our Backs” rallies where injured UPS workers spoke (Teamsters UPS Update, May 30, 1997).

- Another, larger round of rallies focused on job security. Tens of thousands of members blew high-pitched whistles both inside and outside UPS facilities to show management their determination to win gains on issues such as subcontracting (Mitchell, 1997).

- About six weeks before contract expiration, the organization and unity built by the member-to-member networks paid off as more than 100,000 Teamsters signed petitions telling UPS that “We’ll Fight for More Full-time Jobs” Teamsters UPS Update, July 7, 1997). Part-time package sorters and full-time drivers marched together in public demonstrations in cities like Memphis and San Francisco and held rallies throughout the country {The Teamster, August/September 1997). “In years before, we weren’t as unified,” said part-timer Brad Hessling in St. Louis. “Feeder drivers would sit over here and have their own break room and package car drivers would sit over there and part-timers over there. But early on this year we were talking together and I learned about other people’s issues. By the end, we had enough reasons that we could all stick together.”

As workers united, they began to see their own power. At UPS’s distribution center in Jonesboro, Arkansas, Teamster members came to work wearing contract campaign stickers. Their supervisor fired the union steward and told the other workers to take their stickers off or leave. They left—to talk to a local television station. Late that night, higher management called to apologize and assure the workers that if they came back to work they would be fully paid for the time they missed (Convoy Dispatch, August 1997).

In coordination with the union’s field organization, the Teamsters communications strategy was geared toward building a contract campaign that got workers involved. While UPS spent more than a million dollars on newspaper advertising containing pronouncements from corporate headquarters, the union spent no money on advertising at all. Instead, the union concentrated on organizing rallies and other actions that attracted the news media and where rank-and-file workers were among the featured speakers (Nagoumey, 1997; Candaele, 1997). Bulletins, videos, and other materials featured both full-timers and part-timers telling why they were getting involved in actions to win a better contract for all. To help members speak for themselves, the union provided a steady stream of information through a toll-free hotline, the Teamsters Internet web page, a special electronic “listserv” mailing list for rank-and-file activists, and national conference calls that could be heard at every local union hall.

When the union obtained an audio tape that top UPS negotiator Dave Murray had sent to all supervisors, it prepared its own tape for Teamster stewards to share with rank-and-file workers (Business News Network for UPS Managers, March 1997). Instead of featuring union officials debating the UPS executive, the union’s tape alternated excerpts of Murray’s tape with responses from UPS workers. Murray said that not only was $8 an hour an adequate part-time wage, but in many areas it would be “a fine full-time wage.” Part-timer Adrian Herrera from southern California responded, “I know that they’re making money on our backs. Even if they would give us raises, they’d still make a hell of a good profit” (From the Horse’s Mouth, 1997).

Murray’s taped message also criticized Teamster leaders for keeping members informed on the progress of negotiations. “In the past,” he said, “commitments were made to not speak to the members or the employees for whom the contract is being negotiated. The reason this was usually viewed as a wise position for both parties was that the communication of positions taken during negotiations often raises the expectations of those people who ultimately could be voting on the ratification of the agreement.” Herrera disagreed, saying that “as long as we can make our people aware of what’s going on in the contract, I think we’re better off.”

A Movement for All Workers

From the beginning, the union’s contract campaign at UPS was designed to build the broad public support that would be needed to either win a good contract without a strike or win a strike if that became necessary. For nine months, union communications stressed that the campaign was not just about more cents per hour for Teamster members but about the very future of the good jobs that communities need. Teamster members, in turn, emphasized the same message when talking to the news media and to family, friends, and neighbors.

Local union leaders and activists were encouraged to invite community organizations to rallies and other activities. Many locals organized “Family Days” that symbolized the importance of good jobs for working families. UPS pilots, who belong to a separate union, and Teamster members from other industries took part in many campaign activities (The Teamster, August/September 1997).

The importance of the fight for good jobs in today’s global economy was highlighted by a day of rallies by UPS workers not only in the U.S. but in seven European countries, where the company had invested billions of dollars in trying to expand its operations (Teamsters UPS Update, May 30, 1997; Wall Street Journal, May 22, 1997). At the UPS center in Gustavsburg, Germany, workers handed out leaflets and stickers, wore white socks as a symbolic show of unity, and blew whistles like those being used by Teamster members at actions in the U.S. “The management obviously was alarmed,” reported German shop steward Bruno Hingott, “but I don’t know if because of the international UPS action day, or because of the presence of the district manager who was watching what his most dangerous works council and union group were doing.”

With the groundwork laid for community support, activities to show that Teamster families were fighting for all workers escalated once the strike started. A story that ran on the Reuters wire a few hours after picket lines went up quoted a rank-and-file UPS driver, Randy Walls from Atlanta, saying, “We’re striking for every worker in America. We can’t have only low service-industry wages in this country.” In some areas, striking UPS drivers traveled their regular routes by car, sometimes accompanied by a part-timer, to explain to their customers the broad significance of the strike (Greenhouse, August 25, 1997; Teamsters UPS Update, August 8, 1997). In Seattle, 2,000 people formed a human chain around a UPS hub (Teamsters UPS Update, August 13, 1997). More than 2,000 telephone workers marched in Manhattan to show their support (‘Teamsters UPS Update, August 11, 1997). U.S. Senator Paul Wellstone of Minnesota, Reverend Jesse Jackson, and other national and local politicians walked picket lines (Cassidy, August 9, 1997).

In the union’s national news conferences, rank-and-file workers were

visible spokespeople, emphasizing the importance of the strike issues to all working families. For example, at a news conference in which John Sweeney announced millions of dollars in loan pledges from other unions to maintain strike benefits, part-timer Rachel Howard and veteran driver Ezekiel Wineglass were featured speakers, talking from the heart about America’s need for good full-time jobs and pensions (America’s Victory, 1997).

On August 15—twelve days into the strike—the union announced a major escalation of community activities that would show that the UPS workers’ fight was “America’s fight” (Greenhouse, August 16, 1997; Swoboda, August 16, 1997). Labor-community coalitions such as Jobs With Justice planned actions in some cities to target retail companies such as Kmart and Toys-R-Us that had called on President Clinton to end the strike—not surprising since retail companies are prime abusers of part-time, lower-wage workers. Local Coalitions for Occupational Safety and Health (COSHs) planned news conferences and demonstrations highlighting how UPS had paid academics to help attack federal job safety rights for all workers (National Network of Committees on Occupational Safety and Health, Summer 1997). National women’s groups geared up a series of actions focusing on the effect on women workers when good jobs with pension and health benefits are destroyed.

“If I had known that it was going to go from negotiating for UPS to negotiating for part-time America, we would’ve approached it differently,” UPS vice chair John Alden later told Business Week (Magnusson, 1997).

A Fighting Force for Working People

While some argue that unions must shun the “militant” image of the past in order to maintain support from members and the public, the UPS experience shows the broad appeal of a labor movement that is a fighter for workers’ interests. The union showed its members and the public that it sought solutions to problems, not confrontation for confrontation’s sake. But it also showed that it was willing to stand up to corporate greed when push came to shove.

The first signals came in the one-day safety walkout in February 1994, when Carey drew the line after weeks of seeking a reasonable solution to the company’s demand to raise the package weight limit from 70 to 150 pounds without necessary precautions to protect workers’ safety. It was a rare, if not unprecedented, national union job action over a safety and health issue. Within hours, the company signed an agreement it had been unwilling to make before the walkout (Settlement Agreement, 1994).

Two months later, in April 1994, the International Union led a three- week strike against the major trucking companies in the freight hauling industry in order to stop management from creating $9 per hour part-time positions. The message could not have been more clear: the “throwaway worker” strategy that old-guard officials had permitted for years at UPS would not be allowed to spread to the freight companies by the new International Union leadership (Teamsters Freight Bulletin, April 29, 1994).

Then, in 1995, Teamsters mounted another apparently unprecedented national union campaign—this time to defeat the labor-management “cooperation” scheme that UPS management tried to establish to weaken the union before the 1997 contract talks. The International Union coordinated a major membership education campaign highlighting the differences between the company’s promises of “partnership” and the program’s attack on rights under the union contract (The Teamster, January/February 1996). In addition to conducting training sessions at local unions, the International encouraged every union steward to share with other members a video and educational materials on the theme, “Actions Speak Louder Than Words.” Members were urged to ask the company why it didn’t demonstrate its commitment to “teamwork” by working with the union to create more full-time jobs, stop subcontracting, and improve job safety. A program that was supposed to divide Teamster members was turned by the union into an opportunity to build unity heading into national contract negotiations. In fact, the campaign against the Team Concept was so successful that in early 1998 UPS agreed in writing to terminate the program altogether (Parker, 1997; Schultz, 1998).

When bargaining for the 1997 contract began, top Teamster negotiators inspired members with a strategy for staying on offense. It had become common during the 1980s for union leaders to start negotiations by sounding the alarm to members about management demands for major concessions. “Victory” could then be measured not by gains won, but by giveback demands that were defeated. But when UPS management tried to set up that same dynamic by proposing big concessions, Teamster leaders broke off negotiations to show they weren’t willing to play along (Why Won’t Management Listen?, undated).

“This billion-dollar company must be living on another planet to waste our time with proposals like these,” Carey told members in a contract campaign bulletin. “These negotiations are about only one thing—and that is making improvements that will give our members the security, opportunities, safety, and standard of living that they deserve” (Teamsters UPS Update, May 30, 1997).

Union leaders also stood up to UPS’s proposal to take over workers’ health and retirement funds. The company proposed to leave the regional or local Teamster pension plans that cover union members from a variety of companies. Instead, UPS would set up its own pension fund that it would control. The pitch to UPS workers was that, as a younger work force, they could enjoy better benefits in their own plan. “By establishing a plan exclusively for UPS people, our hard-earned dollars would no longer subsidize the pensions of non-UPS employees,” management wrote in a letter to employees (Shipley, 1997).

UPS had raised the same proposal in past negotiations as a bargaining chip, taking it off the table at the last minute in return for union acceptance of other concessions (Teamsters UPS Contract Update, October 1, 1993)

But in 1997 the union refused to play that game, instead confronting the issue head on. Union leaders explained to members that by pooling retirement money from a large number of employers, Teamster plans provide better benefits and more security. When the stock market rises and pension funds earn extra investment income, that money stays in the Teamster plans to help raise benefits and provide protection for the future. In contrast, management’s plan would give the company the right to skim off extra investment income and use it for executive bonuses or any other purpose. With nine days to go before the contract would expire on July 31, 1997, Teamster leaders sent another clear signal that the union had become a fighting force for change. Management was demanding that the union accept a “final offer” and agree to a contract extension while details were worked out—arguing that customers would shift to other delivery services without immediate assurances that there would be no strike (UPS, Inc.’s Last, Best and Final Offer, 1997). But once again, the union refused to be put on the defensive. It ridiculed the idea that bargaining was over and continued to make counter proposals.

On July 30, management tried again, making another “final offer” and demanding that it be put to a membership vote. Again, the union stood firm. There would be a membership vote when the union committee had negotiated an agreement that met the needs of working families, and not before. At the request of a federal mediator, Teamsters negotiators bargained for three days past the deadline in a good-faith effort to reach a settlement. When management still wouldn’t budge, union members had no alternative but to strike.

During the walkout, the union showed it was a fighting force for working people by standing up not only to one of the biggest employers in the world but also to a variety of politicians trying to bring pressure for a settlement. Republican leaders such as House Speaker Newt Gingrich called on President Clinton to order the strikers back to work without a contract. The Clinton Administration tried to jawbone both sides. But Teamster leaders made it clear that the strike would not end until an agreement was reached that provided the good jobs that America needed (Greenhouse, August 11, 1997; Swoboda, August 12, 1997).

Seeing that the strike was building momentum as it headed into the third week and that public support was growing in both the U.S. and Europe, UPS management caved in on every major issue. The company agreed to create 10,000 new full-time jobs by combining existing part-time positions—not the 1,000 they had insisted on in their July 30 “last, best, and final” offer. They would raise pensions by as much as 50 percent—and do so within the Teamster plans, not under a new company-controlled plan. Subcontracting, instead of being expanded, would be eliminated except during peak season, and then only with local union approval. Wage increases would be the highest in the company’s history, with extra increases to help close the pay gap for part-timers. The only compromise by the union was to accept a contract term of five years instead of the four-year term of the previous agreement (Greenhouse, August 19, 1997).

The Teamsters 1997 campaign at UPS, like any contract fight, was affected by specific circumstances that wouldn’t always be present in other situations (Greenhouse, August 20, 1997). Years of rank-and-file organizing by TDU had laid the groundwork for effective contract campaign networks on the job. UPS controlled about 80 percent of the ground package delivery business, which ensured that a strike would have significant economic impact and bring pressure on the company to settle. The company was not a conglomerate with other major lines of business that could help it withstand the walkout. Because UPS delivers to every address in the U.S., the strike was a hometown story in nearly every city and town. Because it took place during August, when Congress was out of session in a non-election year, it was easier to generate maximum attention from the national news media.

Despite these particular factors, the campaign clearly demonstrated the importance of worker involvement and community outreach in building labor power, and that lesson was underscored when the union allowed its new power to slip away by abandoning those approaches after the strike. Three days after the strike was settled, federal overseers overturned Carey’s 1996 reelection victory, and three months later they forced Carey out of office because of campaign finance violations.

Sensing an opportunity to take advantage of a leadership vacuum, UPS management refused to combine part-time positions to create the 2,000 new full-time jobs required in the first year of the contract (Blackmon, 1998; Mitchell, 1998). With Carey no longer on the scene to lead a rank-and-file campaign, old-guard leaders who controlled most local unions reverted to their traditional “don’t-rock-the-boat” relationship with the company and did nothing to enforce the agreement. After one half-hearted round of public demonstrations, the International let old-guard locals and the company off the hook by seeking a solution only through the contract’s grievance procedure, a legalistic process whose outcome would depend on a decision by a neutral arbitrator after many months or even years of delay.

While the return to old ways demoralized many workers, others drew the same conclusions from the 1997 contract campaign that academic observers have drawn about the critical role played by rank-and-file unionism in revitalizing labor power (Clark, 1981; Mantsios, 1998; Moody, 1998).

“The whole experience started my hunger for knowledge about the labor movement in general, about the Teamsters in particular, and about what role I might have in changing the shop in which I work,” said driver Rick Stahl of Boston. “We now need to work on building a rank-and-file unity in this local that understands the importance of union representation and what democracy can mean to that process” (Convoy Dispatch, April 1998).

“People are just now learning what a union can do for them,” said UPS part-timer Kathy Gedeon. “We now feel like we have a say-so” (Johnson, August 6, 1997).

Gloria Harris, a UPS worker in Chicago where workers from diverse backgrounds joined together on picket lines, added that “we now feel more like brothers and sisters than coworkers.” “We all learned something about color,” she said. “It comes down to green” (Johnson, August 20, 1997).

Contact the authors at: rand.wilson@gmail.com

References

Actions Speak Louder than Words (1995). Teamsters videotape.

America’s Victory. The UPS Strike of 1997 (1997). Teamsters videotape.

“An Interview with UPS Corporate Labor Relations Manager Dave Murray” (1997). Labor Relations Update. Business News Network for UP5 Managers Special Edition (March).

Associated Press (1994). “Teamsters Union Ends Strike Against UPS.” Kansas City Star (February 8).

Blackmon, Douglas (1998). “UPS Nullifies Part of Teamsters Contract.” hell Street Journal

(July 10).

Blackmon, Douglas, and Glenn Burkins (1997). “UPS’s Early Missteps in Assessing the Teamsters Help Explain How Union Won Gains in Fight.” Wall Street Journal (August 21).

Candaele, Kelly (1997). “Teamsters Go for Public’s Heart.” Los Angeles Times (August 17). Cassidy, Tina (1997). “Omcials Join Teamsters at Rally.” Boston Globe (August 9).

Clark, Paul F. (1981). The Miners’ Fight for Democracy. Ithaca: Cornell ILR Press.

Countdown to the Contract: 199O—1997 Teamsters Contract Campaign Planner (1996). International Brotherhood of Teamsters pamphlet (July).

Crowe, Kenneth C. (1993). Collision: How the Rank and File Took Back the Teamsters. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Drew, Christopher (1995). “In the Productivity Push, How Much is Too Much?” New York Times (December 17).

Field, David (1997). “Poll: 55’7o Support Strikers at UPS.” USA Today (August 15).

From the Horse’s Mouth. UPS Management Debates Teamster Members on Our Next Contract (1997). Teamsters audiotape.

“Good Time to Help Organize” (1997). The Teamster Magazine (October): 4.

Greenhouse, Steven (1997). “United Parcel Asks Clinton to Intervene in Walkout.” New York Times (August 11).

Greenhouse, Steven (1997). “Long Hours Fail to Budge UPS Talks, Carey Says.” New York Times (August 16).

Greenhouse, Steven (1997). “In Shift to Labor, Public Supports UPS Strikers.” New York Times (August 17).

Greenhouse, Steven (1997). “Teamster Officials Report a Tentative Pact With UPS to End Strike after 15 Days.” New York Times (August 19).

Greenhouse, Steven (1997). “A Victory for Labor, But How Far Will it Go?” New York Times

(August 20).

Greenhouse, Steven (1997). “Yearlong Effort Key to Success for Teamsters.” New York Times

(August 25).

Half a Job Is Not Enough. How the Shift to More Part-time Employment Undermines Good Jobs at UPS (1997). Teamsters Research Department (June).

Holding the Line in ’89: Lessons of the NYNEX Strike (1990). Boston: Center for Labor Education Research.

Johnson, Dirk (1997). “Angry Voices on Pickets Reflect Sense of Concern.” New York Times

(August 6).

Johnson, Dirk (1997). “Rank-and-File’s Verdict: A Walkout Well Waged.” New York Times

(August 20).

La Botz, Dan (1990). Rank and File Rebellion. New York: Verso.

Magnusson, Paul (1997). “A Wake-Up Call for Business.” Business Week (September 1).

Make UPS Deliver (1996). Teamsters videotape.

Mantsios, Gregory (ed.) (1998). A New Labor Movement For the New Century. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Mitchell, Cynthia (1997). “Teamsters Break Off Talks, Criticize UPS.” Atlanta Constitution-Journal (May 23).

Mitchell, Cynthia (1998). “The UPS Strike Revisited: What Lessons Did They Learn?” Atlanta Constitution-Journal (August 2).

Moberg, David (1997). “The UPS Strike: Lessons for Labor.” Working USA (September/October).

Moody, Kim (1988). An Injury to All. The Decline of American Unionism. New York: Verso.

Nagourney, Adam (1997). “In Strike Battle, Teamsters Use Political Tack.” New York Times

(August 16).

Nissen, Bruce (ed.) (1997). Unions and Workplace Reorganization. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Parker, Mike, and Jane Slaughter (1994). Working Smart: A Union Guide to Participation Programs and Reengineering.Detroit: Labor Notes Books.

Parker, Mike (1997). “Fighting UPS ‘Teamwork’ Prepared Union to Win the Big Strike.” Labor Notes 224.

“One of the Best Organized Centers in the U.S.” (1997). Convoy Dispatch 161 (August).

“Over 30,000 Win Teamster Representation in 1997” (1998). The Teamster Organizer, Newsletter (Spring).

“Part Time, Full Time, Union Time” (1997). The Teamster Magazine (March/April): 6.

Schultz, John (1998). “Coercion or Cooperation?” Traffic World (March 2): 19.

SEIU Contract Campaign Manual (1988). Service Employees International Union and American Labor Education Center.

Settlement Agreement on Handling Over 70 Pound Packages (1994). International Brotherhood of Teamsters (February 7).

Shipley, Harry (1997). Letter to employees from UPS District Manager Harry Shipley (August 11).

“Strength In Numbers” (1998). The Teamster Magazine (March): 12.

Sweeney, John (1997). Keynote address at 22nd Constitutional Convention, AFL-CIO, Pittsburgh, PA (September 22).

Swoboda, Frank (1997). “Labor Official Calls in Vain for New Talks.” Washington Post (August 12).

Swoboda, Frank (1997). “Carey Says UPS Talks Making No Progress—Teamsters Call for Stepped-Up Strike Activities.” Washington Post (August 16).

Teamster Magazine (1997) (August/September): 3.

Teamsters Freight Bulletin (1994) (April 29).

“Teamsters Roaring Down on McD’s” (1998). Vancouver Province (March 19).

“Teamsters to Pressure UPS Through Rallies in U.S. and Europe” (1997). Wall Street Journal (May 22).

“Teamsters Uniting to Make UPS Deliver” (1996). The Teamster Magazine (November/December): 8.

Teamsters UPS Contract Update (1993) (October 1).

Teamsters UPS Update (1995) (November).

Teamsters UPS Update (1997) (May 30).

Teamsters UPS Update (1997) (July 7).

Tilly, Chris (1996). Half a Job.’ Bad and Good Part-time Jobs in a Changing Labor Market. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

UPS Contract Proposals (1997) (March 27).

UPS, Inc.’s Last, Best and Final Offer of Settlement for the National Master Agreement (1997) (July 22).

UPS’s Stealth Campaign Against OSHA: The Link to Scientists and Think Tanks (1997). National Network of Committees on Occupational Safety and Health (COSH) and the AFL-CIO Health and Safety Department (Summer).

“UPS Strike Showed Need For Union” (1998). Letter to the editor from Rick Stahl. Convoy Dispatch 167 (April): 11.

Walpole-Hofmeister, Elizabeth (1996). “UPS Establishes Teamwork Program: Encounters Resistance From Teamsters.” Daily Labor Report. Bureau of National Affairs (February 5).

Wells, Donald M. (1987). Empty Promises. Quality of Working Life Programs and the Labor Movement. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Why Won’t Management Listen? (undated). Teamster contract campaign leaflet.

Witt, Matt (1979). In Our Blood. New Market, TN: Highlander Center.

“Workers in Wonderland” (1996). The Teamster Magazine (January/February): 12.

1996 UPS Teamster Bargaining Survey (1996).