Gentrification, Homelessness and Elections: When Does a Difference Make a Difference?

By Kurt Stand

The primary elections in Washington, DC and Maryland are over. For many of the down ballot local races in the District, and neighboring Prince George’s and Montgomery counties, that means the outcome is known, given the predominance of one-party rule in much of our area. At the time of writing, the results are a mixed bag. Some genuinely committed activists for social justice, including DSA members, were elected, and there is now a possibility that some too long-delayed social reforms and protections may be enacted in suburban Maryland. Yet institutional barriers blocking those who would challenge existing power remain high. Moreover, more than a few of those elected are content to let business as usual remain unchanged — for even in relatively liberal communities, in which public officials say all the right things, the gap between words and deeds is enormous and too many people go tumbling down that gap. Co-governance, a form of collaborative engagement in which elected officials meet and work with community groups before and after an election campaign, offers one possible way to overcome that reality.

Nonetheless, for many people in and around our nation’s capital and for millions across the country, elections don’t seem to carry much meaning. That is true of federal races, even in today’s polarized political climate, where candidates spew promises unlikely to be fulfilled, appearing, and disappearing like actors on a stage. And this is true on the local level where even office holders who live within shouting distance too often seem uninformed regarding intimate questions of food, transportation, school, jobs, health, public safety, and prices. In both cases, such attitudes reflect an eroding of political democracy that lies in the background of our eroding rights. Withdrawing from electoral activity is no answer; but if we fail to understand why so many feel ready to do just that, if we fail to understand that such attitudes are rooted in experience, we will be unable to preserve existing rights – let alone build a transformative politics rooted in alternative power.

Glancing through the July issue of Street Sense – a newspaper of, by and for the unhoused – one can read multiple reflections on the reality of powerlessness in the face of official hostility. In the aptly titled article “Breaking up encampments is worse in the summer heat,” writer Amina Washington, herself homeless, details the DC government’s practice of destroying shelters set up by those without other housing. Washington makes the simple point that those in power choose to evade: “It is unfair to target homeless people and jail them for trying to survive. Sleeping outside should not be a crime.”

Also in the issue, in an article headlined “Watchdog group finds profits soaring for real estate company facing several lawsuits,” Holly Rusch touches on the reason behind the cruelty in police destruction of encampments: realtors profit by raising rents to a level that few can afford, facing no accountability for legal violations they commit enroute to making even more money. So it is that the rich become richer, no matter what the law says. Unstated is that the poor are unwanted in neighborhoods in which they once lived because, much like unkempt lawns, they might lower the value of overvalued properties. Criminalization of homelessness is simply the reverse side of the gentrification coin.

These articles are reporting on realities that have a multi-year lineage – go back to any past issue of Street Sense DC (and editions of Street Sense in other cities across the country) and similar themes of officially sanctioned police repression and unsanctioned landlord profiteering recur with depressing regularity. Washington’s Mayor Muriel Bowser falls into a long line of those in government who pretend concern for those without, shelter yet implement policies that seek a solution by pushing the unhoused out of sight, rather than housing them. The fact that she was an avid supporter in 2020 of Michael Bloomberg – real estate and news magnate, one-time Republican turned anti-Trump but pro-gentrification Democrat – in his presidential primary campaign reflects the deep-rootedness of the problem.

The paper does try to give readers hope, and so there are articles about hearings and investigations that purport to be looking for solutions. These, too, have an air of familiarity to them, for the problem of lack of housing, of lack of services, of lack of health care, of lack of well-paying jobs, of a lack of government accountability to the overall community which it allegedly serves and in whose interest it allegedly acts, are “problems” endlessly discussed, studied, analyzed, legislated for, and yet ever unresolved. Street Sense’s community speaks with more honesty in poems and bits of autobiographical writing that seek meaning in personal relationships or spirituality – graspable in a way our political system should be but is not.

That is the challenge which newly elected or re-elected public officials now face: how to act in ways that become meaningful for those whose needs are greatest; how to bring about reforms that challenge existing injustice; how to rearrange the current power structure into one that is more fair and sustainable. In both DC and in Maryland, progressive legislation around hours, wages, sick leave for workers and police accountability have all passed in recent years. These matter enormously. Yet the fact remains that for far too many, words on pages have not translated into a difference in conditions of life.

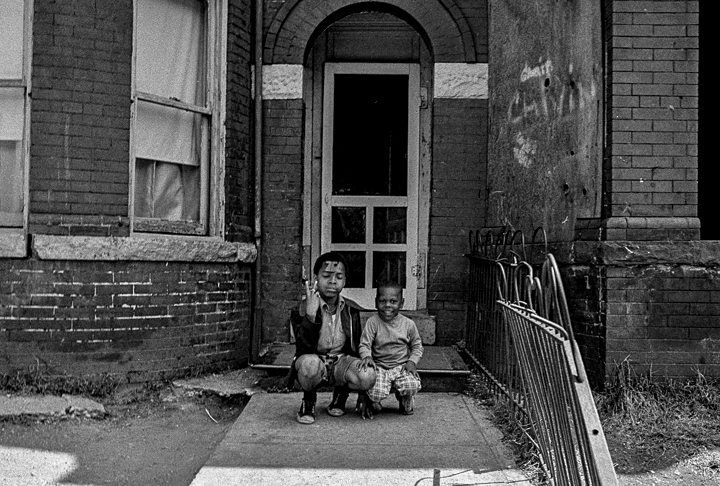

PHoto of young boys on stope 3 blocks from the Capital, 1972 now an area with high property values and well to do residents

That gap is not only experienced by those of us with the least. Renters, homeowners, working people doing better, people defined as “middle class” (in all that term’s ambiguity) continually find themselves navigating changes in the quality of their lives due to fluctuations in the housing market without any meaningful say in the process. Living in a neighborhood that forms part of a community is valuable in and of itself, something most people desire, but it is not a value that market forces put on property. A home that becomes an asset to be flipped loses an intangible quality of what “home” could be.

Unwanted change as a fact of life came through in a performance of Green Machine at Capital Fringe Festival earlier this month (an annual independent theatre program back after two Covid-canceled seasons). Written by Jim McNeill and directed by Catherine Aselford, the one-act play gives voice and dimension to the lived reality of a neighborhood in transition and the accompanying lost sense of community that arrives when real estate interests “improve” an area by raising home prices beyond the beyond. Gentrification is a fancy name for that process; another word for it might be displacement, as those who can’t afford simply “disappear” — forced out of their homes, forced to start over again, moving in with family or winding up on the streets. Other losses occur too, less tangible yet no less real – and such losses are those to which the play’s characters give voice.

Set in D.C.’s Mt. Pleasant neighborhood – a community which had its own vibe as a mixed black, white Central American community with more street life than is commonly found in our nation’s capital. The play is rife with references that speak to an understanding of what was as well as what is, as it depicts a community where a house originally purchased for tens of thousands of dollars might now be worth millions. Upward prices increase the push-pull of high turnover – whether selling is designed to cash in before a price fall, or forced as rising taxes, interest rates, insurance make what has long been home, unaffordable. Winds of change for homeowners hit tenants with gale-like force as their rents and rights are ever less protected. In the process, the vibrancy of what had been disappears. Wealth comes attached with its own bland uniformity and multiple layers of segregation – be it by race, income, age – ultimately enforcing complete homogeneity of lifestyle, as what is or is not “acceptable” narrows.

Those details are implied in Green Machine, which focuses on how longtime residents try to make sense of what has happened to their lives, to the world they lived in. A community where people knew each other, where someone would feel safe enough to lend a stranger a helping hand, where neighbors befriended multiple generations of a family, somehow vanished without any single event marking the beginning (or end) of the transition.

Breathing life into this narrative is that every time someone spins too rosy a picture of the past, someone else brings back a moment of reality with a reminder that it wasn’t just about peace and love, that crime existed, that money mattered. However, problems were community problems. They weren’t brushed aside, ignored or dealt with by moving out or forcing “undesirables” away.

Green Machine‘s plot revolves around the opening of a marijuana dispensary – of questionable legality in the here and now as only regulated medical marijuana dispensaries are currently permitted – aiming to cash in on the possibilities of the likely soon-to-come full legalization without abandoning the sense of trust that was part of the bygone counterculture. Those illusions, too, are shattered: we can’t go back to all the past, all the more so because that alternative culture was itself never able to overcome either the pull of market forces nor the social dysfunction that lies just beneath the surface of our lives. The thin line between drugs as a means of social connection and drugs as a force of destruction is not glossed over, as the fate of ungentrified neighborhoods left behind are noted in the play as a reminder of other, deeper losses. Yet, failure doesn’t deny the fact of what was: the vibrancy, the sense of possibility around which neighbors tried to build a life was real and was lost when neighbors become strangers. One character recalls falling down drunk on a winter’s night and how a neighbor whom he didn’t know took him in, an example of trust in a stranger who was thereafter no longer a stranger. Even when characters differ in memory they share memories of people over time, people without anything else in common but whom they knew because of the community that existed.

The play never loses sight that while property values have gone up, the change that came was for the worse – as notes included on the playbill back up:

In 1968, following the violence that erupted in response to the assassination of Martin Luther King, white flight led to Mt. Pleasant becoming a majority black neighborhood. 1980s;

a large influx of immigrants from El Salvador and other Central American countries creates its own beauty, widening the cultural contours of each block, as well as bringing new tensions that burst forth in street violence in response to a 1991 police shooting;

the millennium, housing prices went up, community diversity went down. The 2010 Census uncovered the fact that the Mt. Pleasant/Colombia Heights/Park View zip code ranked amongst the 25 most “whitened” in the country;

and by 2020’s zip code, the black population had fallen to 12%, the white population, now the majority, risen to 52%;

overall – and the raw fact behind these changes – the Playbill notes that a friend of the playwright purchased a home in Mt. Pleasant in 1972 for $22,000 – today the same home is assessed at $1.2 million.

All those numbers don’t tell what the play recounts: that for about three decades a thriving community was built in Mt. Pleasant. Now take those numbers and look at the unhoused, look at the reality facing residents of Congress Heights, of Deanwood or other left-behind neighborhoods in DC where jobs are scarce, social services few, housing dilapidated and violence all too common – or look at the similar disparities in Prince George’s and Montgomery Counties – and a picture emerges of few winners and more losers, of a preponderance of insecurity whatever one’s income, an insecurity made exponentially worse when it is wrapped within a life of poverty.

No one voted for this change – it just “happened.” Or rather, the cash ballot has more heft than the one in the voting booth. Changes brought about by market forces never just happen; public policy set in motion by specific legislation creates or inhibits the cycles of boom and bust that mark our lives, leading to the monetization of all aspects of life that hover around the characters in Green Machine and the vendors selling Street Sense.

Unions, community associations, churches, social justice groups, and socialist and other left-wing organizations exist in Mt. Pleasant as they do more broadly in DC and suburban Maryland. Many were aware of encroaching gentrification and displacement, and tried to push for an alternative. Yet these organizations were too small, too weak to have the needed impact. Or perhaps, better put, they had not been sufficiently integrated into the daily life of the communities within which they work and thus were (and are) relatively powerless. This is a problem for local officials as well –the most principled elected social justice advocate in the world will lack effectiveness if their work is not intimately linked with grassroots organizations that are themselves part of popular daily life.

This is the challenge we face now. Elections matter – legislative and political alternatives can redirect society, reveal conscious choices that lay hidden when the “market” is blamed for the consequences of a system built on greed. Moreover, all we need do is look across the Potomac and see the Republican sweep in Virginia last year to understand that complacency jeopardizes the rights we so urgently need to make life better for all. If we turn back to the 1990s (the midway point in the sweep of time that forms Green Machine’s characters’ understanding of the world), we can see the cost when we are unable to resolve community pain in a human and humane fashion.

That was the time of the crack epidemic and inner-city destruction in our area and across the country. This also marked the Reagan-era devastation of the gains made by civil rights and liberation movement struggles and laid the groundwork for the wave of gentrification and displacement we now experience. After all, the economics of profiteering goes hand-in-hand with the racism that makes it so easy for some to talk of “neighborhood improvement” that drives out those who would most want and need the benefits of the promised change – just as it makes it easy to see the unhoused as a problem to be removed from sight rather than as people with problems that need to be resolved. Writing in 1991, Clarence Lusane took note of connections we still need to make:

“A radical redistribution of wealth and an examination of the prejudices of the capitalist economic system must be at the core of a movement led by people of color and working people for fundamental economic reform. … While economic parity alone will not end either individual or institutional racism, it is the foundation upon which to build the movement for an egalitarian society. None of these suggestions are remotely possible without increased economic and political power on the part of those most dispossessed in our society, particularly communities of color. … Strategies for increased and responsive political power and economic development must come from those communities most in need.”

(Pipe Dream Blues: Racism & the War on Drugs, South End Press, Boston, 1991, p. 220).

Despite often heroic and determined efforts, popular movements in the 1990s were unable to realize such power. So the initiative passed to the hands of those who found a source of wealth in others’ poverty – money making money by undermining community, by devaluating neighborhoods, by raising the cost of housing, thereby destroying the sense of home so crucial to us as human beings. How that can be made different is the dilemma posed by Green Machine, is the moral imperative that cries out from the pages of Street Sense, and is the challenge elected officials face today, as violent assaults on democratic rights in any form loom as a direct threat.

Co-governance, as noted, is one way to create a social justice alternative to the lobbyists who push forward the notion that only incremental change is possible, incremental change only permitted when accompanied by giveaways to those who already have too much. It is a way to ground politics that can build the change people need by creating wider bonds of unity (such as between homeowners and the homeless) rather than new divisions. It is up to us to build organizations of all those impacted, organizations that are part of the fabric of life. It is up to us to create a political culture connected to the rhythms of life, to ensure that we can and do use and expand our rights. It is up to us to create the communities we long for, rather than those imposed by the logic of the dollar. Only if we do so will we find an escape from the atomized, displaced existence that continues to threaten us today.

…