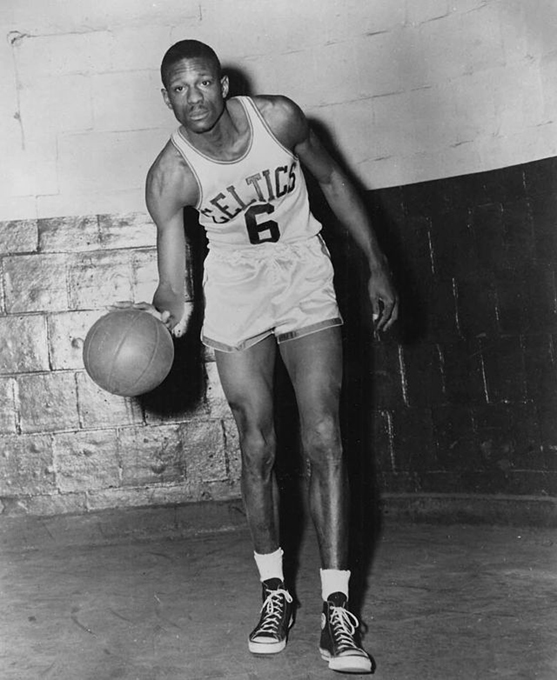

Bill Russell, “played for the Celtics not for Boston.”

By Jay McManus

No one, especially basketball fans, in the Boston area could escape the shadow of Bill Russell and his Celtics in the 1960’s. He and his teams were so good that it was news only when they lost. That greatness has been acknowledged non-stop since Russell’s recent death, but it is still very difficult, even for us Bostonians who lived through them, not to be amazed by his core accomplishments: eleven NBA championships in thirteen years, including eight in a row. Russell was, unmistakably, at the heart of the engine for the Celts, just as he was at the University of San Francisco, where he won two national titles, and on the 1956 gold medal-winning US Olympic team.

He revolutionized the NBA. In stark contrast to today’s play, Russell emphasized defense, leading schemes that were near impenetrable and utilizing a style that epitomized teamwork and selflessness. It’s arguable that no athlete ever, in any sport anywhere, has subjugated his supreme skills for the good of his team like Bill Russell did. Personal accomplishments and glory meant nothing to him. That Russell was able to add to such an incredible legacy by winning two championships as a player-coach—a role virtually unheard of at the professional level of any sport worldwide before or since—underscores the singular talent, intelligence, and commitment of the man.

Many in Boston ignored it all. Despite their historic run, the Celtics often played before a half empty Garden; even the playoffs didn’t guarantee sellouts. No parades, player endorsements, and public clamor awaited these champions. Instead, as another Boston legend, Bob Cousy, put it, a “nice dinner” capped their winning seasons. Meanwhile, their hockey counterparts in Boston, the Bruins, were celebrated by locals notwithstanding their history of losing.

It was difficult back then, as it is now, to believe that race was not the primary reason for the seeming indifference exhibited by Bostonians toward the Celtics. The team was the first in the NBA to start five Black players. Russell was one of the first Black men to play, or certainly star, in the league, and he was later the first to assume the role of head coach for a major professional sports franchise. He also freely expressed his views about the unwelcoming atmosphere in which he and his Black teammates were forced to work.

Russell considered Boston to be one of the most segregated cities in the country, famously referring to it at one point as a “flea market” of racism. On numerous occasions he and his family suffered personal indignities because of their skin color. What ensued in the city only a few years after his retirement in 1969—Black children in school buses being stoned in white neighborhoods, white politicians spewing racist hate, Alabama’s segregationist Governor George Wallace finding a welcome in parts of the city, among other damning indicators—proved his point. It also helps explain another famous sentiment of his that he “played for the Celtics not for Boston.”

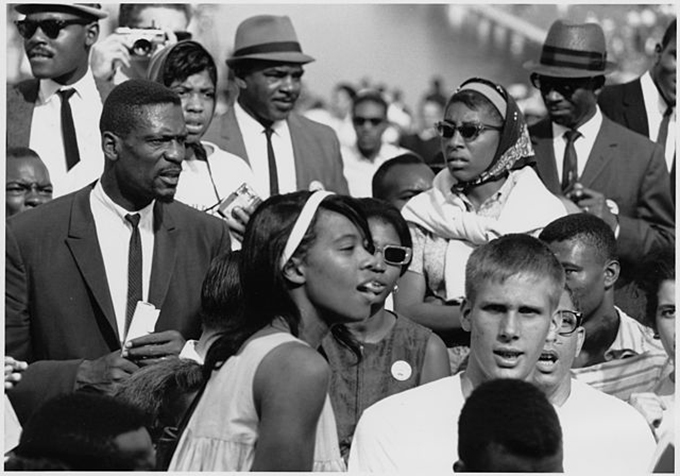

That honesty from Russell, his willingness to speak truth to power, led to his assuming a leadership role in our country’s fight for racial justice. Along with several prominent athletes and entertainers he was—at no small risk to his life and career–part of many of the US civil rights movement’s seminal protests throughout the sixties. The man’s integrity and courage, particularly at such a tumultuous time in our nation’s history, were alone worthy of acknowledgement and formal recognition.

Yet, those achievements, like his historic Celtics run, were also largely ignored, if not clearly resented, by many in Boston including, apparently, its power brokers. More than four decades went by before the city gave serious consideration to paying public tribute to the man, and even then it was only at the urging of then-President Obama who, after awarding Russell the Presidential Medal of Honor in 2011, expressed his wish that “one day, in the streets of Boston, children will look up at a statue built not only to Bill Russell the player but Bill Russell the man.”

It’s not as though Boston didn’t have opportunities to pay proper respect to a civil rights champion who also happened to be professional sports’ greatest ever winner. Years before Obama prodded the city, other Boston sports luminaries, all white if keeping score, had gotten their due with sculptures or equivalent tributes. One of them, Red Sox great, Ted Williams (for the record, no championships in his career), had a major tunnel running through the city named for him in 1995, prompting Russell’s late Celtic teammate, Tom Heinsohn, to offer his own unique take on the disrespect accorded by the city to his friend: “Look all I know is the guy won two NCAA championships, 50-some college games in a row, the ’56 Olympics, then he came to Boston and won 11 championships in 13 years and they named a fucking tunnel after Ted Williams!”

A statue of Bruins great, Bobby Orr, was erected in 2010 in front of TD North Garden, the home of the Celtics. In addition to his tunnel, Ted Williams had a sculpture in his honor placed in front of Fenway Park in 2004. Russell’s coach, Red Auerbach, was memorialized in 1985 with a statue at Faneuil Hall. Scores of other notable Boston athletes, from Harry Agganis to Doug Flutie, Larry Bird, and Rocky Marciano, have had their achievements commemorated through statues, or even had arenas named after them. No doubt there will be a likeness of Patriots quarterback Tom Brady soon gracing the front of Foxboro Stadium.

Boston’s monument to Bill Russell, by far the most accomplished and consequential icon of them all, erected at last in 2013, is found off to the side of Government Center Plaza, hardly a hub of activity for people in the city, and especially for tourists; blink and you’d miss the statue. The setting does not befit an athlete and man of Russell’s stature. Worse, it fuels the lingering perception, if not reality, that in Boston only our white sports heroes are deemed worthy of true honor.

Bob Ryan, a long-time sports columnist, and former Celtics beat writer for the Boston Globe recently penned a tribute to Bill Russell in which he cited the varied, and incomparable, contributions he made to the city of Boston. Ryan ended his piece with this question: “Did we deserve him”? For many of us Bostonians the answer, sadly, is self-evident.

…