The Democratic Working-Class Possibilities of Art

By Jay Youngdahl

Art and art making today has two roles.

Creating and enjoying art is a capacity of the human condition. It is a useful and pleasurable resource for expression and learning. Art can play an integral role in the construction of a meaningful life, its most important function.

Yet, “high” art, historical or conceptual, has been integrated into an exploitative economic system, captured by the grand museums and a gallery system that have been incorporated into the firmament of the wealthy. Such art exists in and for the market. Its exchange value has been reified as a commodity pitched by Wall Street. The most powerful gatekeepers are the uber-wealthy heads of museum boards, such as the notorious trustee at the Museum of Modern Art, Leon Black, one of the founders of Apollo private equity and Jeffrey Epstein fame, and Warren Kanders, the trustee at the Whitney Museum of American Art and tear gas magnate.

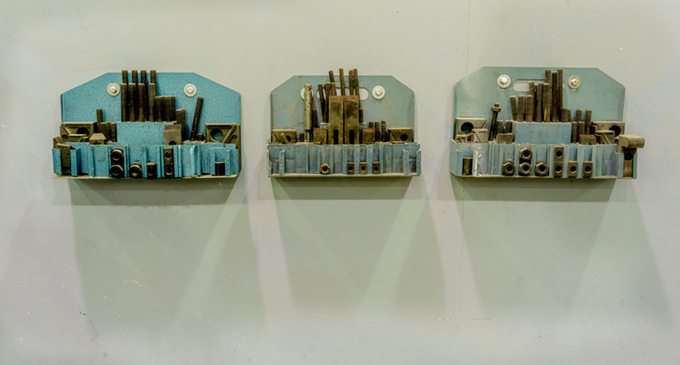

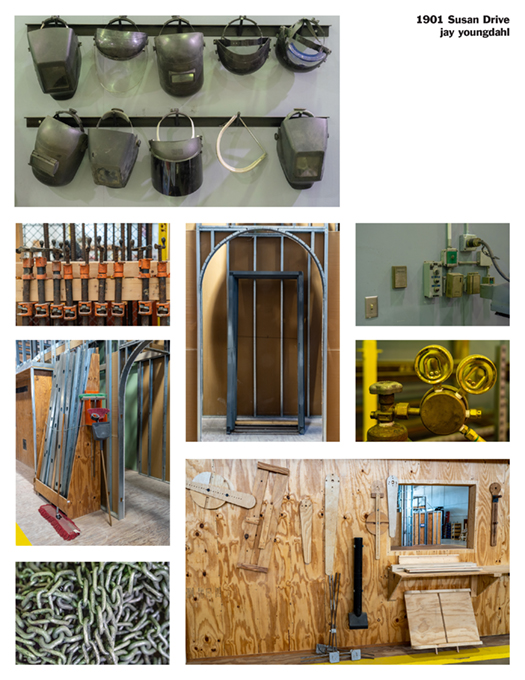

The photos accompanying this article belong to art’s first and most important function. They were taken in a union training center in north Texas in early September 2021. Before a meeting, with the approval of the Director, I walked through the training space with my camera. These photos show the natural efforts of workers who teach and learn the skills needed by carpenters and millwrights. The images are my composition of the art and design in their day-to-day efforts. Few would call these scenes art for art’s sake. They do not feature the opening of a museum and are not the results of the introduction of art teachers. What is shown is the making by workers of their space into an artistic area, an often-unspoken flowering of an innate skill, interest, and ability from those who work here.

When I entered this space at 1901 Susan Drive, it was clean and industrial. Safety concerns due to the nature of the work of carpenters and millwrights, as well as concerns over COVID, could be seen. The building was airy and unsoiled. On a large internal wall, I saw a design that reminded me of a presentation in a large “white box” gallery.

As I walked around the center, the production and design of the space led me to a consideration of how workers make art at work, as part of their work. I saw an underrecognized democracy in artistic production and viewing in an industrial space.

For nearly two centuries, the issues of workers, art, and daily life have been considered in many ways.

Prior to the middle of the nineteenth century in Europe, only depictions of the wealthy and powerful, or those favored by them, were allowed as subjects in figurative paintings hung on gallery walls. In the 1850’s, however, French painters Gustave Courbet and Jean-Francois Millet heroically anchored a turn toward “common” people when they scandalized the Parisian art establishment with their paintings of ordinary French at work. For example, Millet’s painting, The Gleaners (Les Glaneuses),portrayed widows in the countryside forced to gather leavings in the fields to survive, combining skilled artistry with a political position favoring ordinary French.

Some decades later, the question moved from workers as the subjects of art to workers as the viewers of art. As the condition of workers and the poor gained greater recognition in society, artists considered the issue of who could see art, no matter the topic or medium.

The French painter Fernand Leger wanted access for workers to fine art. Leger observed that the problematic issues in art came from our economic system, not from the art itself. As the poor and working class must use their time and labor power to produce enough for the reproduction of their lives, working inside and outside of their living spaces, little time existed for this pursuit. Art’s main problem, Leger argued, is that regular people cannot fathom it; anyone without an academic art degree who has visited a conceptual exhibition in a big city art museum or gallery has experienced this feeling. “One of the most damaging charges that can be made against contemporary modern artists is that their work is accepted only by a few initiates. The masses cannot understand them.” The issue for working people, Leger argued, was not their inability to grasp the concepts and beauty in the art but that an economic structure of work that allowed workers little time for access to the works or the contemplation of them. “Everything is organized to keep them away” from galleries and museums, he wrote.

Is the situation today different? The cost of admission for a family to the great museums of the world can amount to several days’ pay. Off-putting attitudes meted out to those not in the right “tribe” who attempt to enter the great private galleries of the world, like the haughty inattention given to those who attempt to enter a Gucci store on the world’s most exclusive shopping streets, constitute a similar barrier today.

Leger’s humanistic prescription for this malady was for society to offer more free time to workers and their families. He argued, “The masses are rich in unsatisfied desires. They have a capacity for admiration and enthusiasm that can be sustained and developed in the direction of modern painting. Give them time to see, to look, to stroll around. . . The ascent of the masses to beautiful works of art, to Beauty, will be the sign of a new time.” Certainly, we need a “new time” today.

In the early years of the Soviet revolution, the issue of workers and art was on the front burner in a society dedicated to worker well-being and agency. An artistic socialist alternative, bringing art into factories and workplaces was advocated by leaders in the artistic community. Boris Arvatov, an avant-garde artistic activist, promoted the conscious implementation of art into factories in the young Soviet state. Artists would be part of the industrial process, working alongside production workers, as do those with other skills such as logistics, shipping, and accounting.

Recently published in English, in 1926 Arvatov’s book “Art and Production” encouraged an artistic movement called “Productivist Art.” He wondered how artists, with their skills and attention, could contribute to the building of a new society by supporting collective processes of industrial work. Arvatov, his translators wrote, believed that “artists should subordinate their technical skills to the greater collective discipline of the labour process and the workshop. For it is in the factory and the workshop where the erosion of the distinction between workers (as culturally excluded) and artists (culturally privileged), individual ideas and collective creativity will be tested and challenged in practice, and the real work of a new egalitarian culture created.” (Art and Production, translated by John Roberts and Alexei Penzin.)

1901 Susan Drive

The photos here consider the democracy of art, by these construction workers and instructors. To be sure, featured objects and designs are interpreted here by my photos. Learning from Paulo Freire, it is important to acknowledge that my choice and curation of photos come from my human life experience, which is different from those who made and placed the objects. Thus, the images are the product of three human forces – my photographic composition, the graphic design of Nick Ferreira in the poster, and the production of the object and spaces by the workers themselves. Their meaning is in the space bounded by these three human sides.

Thus, these images are a collective effort, as is the work, training and learning in the training center.

…