9/11 + 20 Years – Worker Safety and Health Today

By Earl Dotter and Scott Schneider

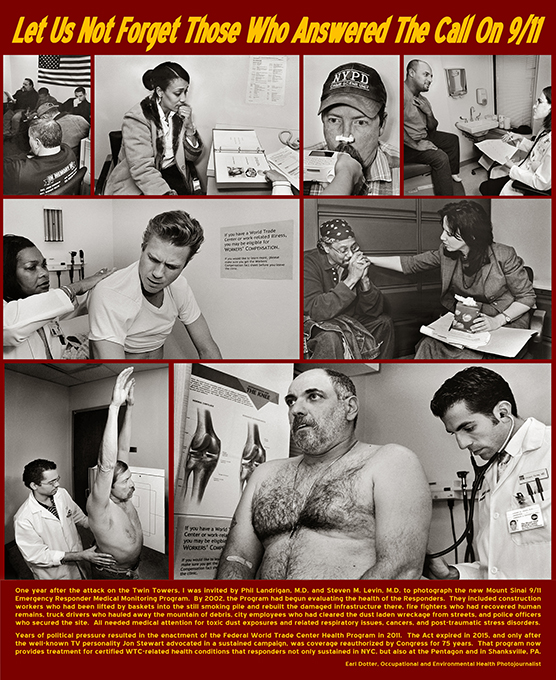

One year after the attack on the Twin Towers, I was invited by Phil Landrigan, M.D. and Steven M. Levin, M.D. to photograph the new Mount Sinai 9/11 Emergency Responder Medical Monitoring Program. By 2002, the Program had begun evaluating the health of the Responders. They included construction workers who had been lifted by baskets into the still smoking pile and rebuilt the damaged infrastructure there, fire fighters who had recovered human remains, truck divers who hauled away the mountain of debris, city employees who had cleared the dust laden wreckage from the streets, and police officers who secured the site. All needed medical attention for toxic dust exposures and related respiratory issues, cancers, and post-traumatic stress disorders.

Years of political pressure resulted in the enactment of the Federal World Trade Center Health Program in 2011. The Act expired in 2015, and only after the well-known TV personality Jon Stewart advocated in a sustained campaign, was the coverage reauthorized by Congress for 75 years. That program now provides treatment for certified WTC-related health conditions that responders not only sustained in NYC, but also at the Pentagon and in Shanksville, PA.

Earl Dotter, Occupational and Enviromental Health Photojournalist

.

Twenty years ago, close to 3,000 people died from the terrorist attacks on 9/11. There are memorials in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and elsewhere, and many commemorations will occur of this tragic event. What has been and will likely continue to be ignored are the thousands of others who didn’t die in the attack but died or suffered as an aftermath of the attack. According to NIOSH there are over 105,000 people enrolled in the 9/11 health surveillance system, 79,000 of who were rescue workers, who are being treated for respiratory illnesses, reflux, asthma, cancer, PTSD and other illnesses.

In sum, 35 times as many people are suffering from the incident as were killed on that day. Yet their stories will likely be ignored because worker safety is often relegated to the back burner in this country. Many people assume that the government guarantees a safe place of work (at least since the OSHA Act was passed 50 years ago) and that workers who get hurt on the job were careless or at fault. Even though the OSHA Act makes it the employer’s responsibility to provide a safe workplace, each year about 5,300 workers are killed on the job. Things have improved over the past 50 years, but it’s not enough. Sadly, those 5,300 deaths are just the tip of the iceberg.

“We need to dramatically reimagine how we approach worker safety and health by giving more power to workers to stop and correct unsafe conditions at their jobsites.”

An estimated 10 times as many workers die each year as those who perished on 9-11 from occupational diseases which are often not counted (in part because the long latency often makes it hard to associate the disease with a particular workplace and in part because the workers compensation system was never designed to count and compensate such illnesses). The system set up by the OSHA Act 50 years ago is largely intact and hasn’t changed much. We still have a disturbingly insufficient number of inspectors — less than 2,000 — to cover over 10 million workplaces. The AFL-CIO estimates that it would take 162 years to just inspect every workplace once.

New hazards such as COVID-19 have emerged for which OSHA has promulgated no enforceable standards (except in 3-4 states that have issued emergency rules this year). The federal OSHA standard that has been issued only applies to health-care workers. New OSHA standards take 7-20 years to issue because of all the regulatory hurdles Congress and the White House impose. The Permissible Exposure Limits (PEL) that OSHA set for toxic chemicals mostly haven’t changed in 50 years and have been disavowed by the agency. States are now struggling to issue new standards to protect workers from heat on the job as the climate crisis has caused the hottest summer on record.

The system is antiquated and broken. We need to dramatically reimagine how we approach worker safety and health by giving more power to workers to stop and correct unsafe conditions at their jobsites. Other places, like the UK, require full time worker health and safety representatives on each jobsite, paid for by the company. Ontario workers have a much stronger right to refuse unsafe work and require joint health and safety committees.

Now, 50 years after the founding of OSHA and 20 years after 9/11, we need a much more robust approach to protecting workers from both injuries and illnesses at work.

Scott Schneider

Former Director for Occupational Safety and Health for the

Laborers Health & Safety Fund of North America (LHSFNA)

…