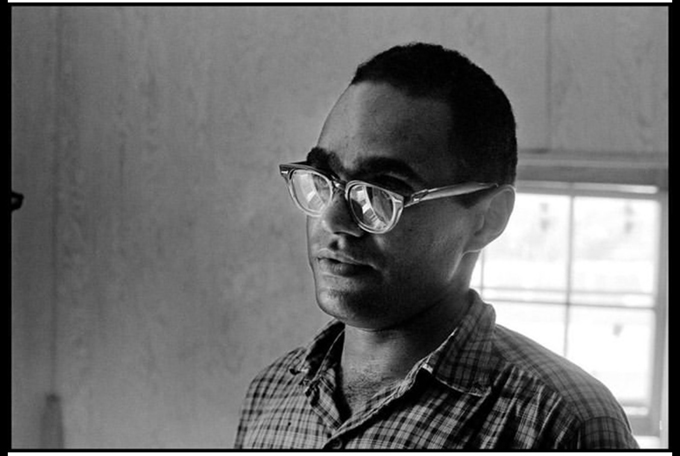

Bob Moses: 1935 – 2021.

By Mike Miller

“This is Mississippi, the middle of the iceberg…There is a tremor in the middle of the iceberg–from a stone that the builders rejected.”

Bob Moses, Letter from Magnolia, MS jail, 1962

An Unlikely Hero

In an age of plastic heroes, Bob Moses is the real thing—in large part because he did not want the role. In Mississippi, where his approach to organizing was born of a deep respect for “local people,” the work he initiated unleashed the talent, energy and power that is there waiting when small “d” democracy has the space to operate.

That space is called democratic organization: small “d” so that it is not confused with the American democratic myth that says when you choose between competing brands called political parties, and the products called candidates that they offer, you have a democratic society. “Organization” so it is not confused with the occasional uprisings of mass mobilization that take place when oppressed people rise in anger only to return to internalized anger when power structures fail to respond; or when voters massively turn out for the lesser evil (however real and necessary that might be) in the hope that it will be more. In SNCC, we thought “organization” is what we did while “mobilization” is what Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference did.

“… what Black Mississippians needed was the right to vote.”

Ella Baker, another genuine hero of The Movement, introduced Bob to a network of Mississippi African-Americans who in 1961 were leaders in local branches of the NAACP or independent local citizenship organizations seeking voting rights. To dare to attempt registering to vote was to put one’s life on the line, and to risk firing, eviction, foreclosure or other economic consequences.

Amzie Moore, one of those leaders in Cleveland, MS, admired the courage of young people sitting-in and engaging in freedom rides but he told Bob that what Black Mississippians needed was the right to vote. His view was repeated by others.

Wesley Hogan describes Bob’s local Mississippi introduction in Many Mind, One Heart (my additional observations are italicized):

…In July, 1961, when [Bob] Moses first arrived in McComb, Webb Owens, a retired railroad employee and treasurer of the local NAACP, picked up Moses and began making the rounds to every single black person of any kind of substance in the community. For two weeks, during each visit, Moses conversed with these leaders about his proposal to undertake a month-long voter registration project. Other SNCC staff would come to help, he promised, if the community raised money to support them.

At that point, Owens moved in as a closer. A smart, slim, cigar-smoking, cane-carrying, sharp-dressing gregarious man known in the community as “Super Cool Daddy”, liked and trusted by all, Owens solicited contributions of five to ten dollars [equal to $45 – $90 in 2021 dollars] per person. Before the rest of the SNCC staff arrived, the black community not only supported the project, it financed it as well.

Surfacing here is one of the central causal dynamics of the civil rights revolution in the South of the 1960s…Moses would approach a local leader—in this case, Webb Owens. He then listened to Owen’s ideas…

…Owens led Moses to all of the potential leaders in the community, in the process exposing himself to great risks as a local NAACP leader. When he extended himself on behalf of Moses and asked citizens to financially support a voter registration drive, things began to happen. The quality of the local person that you go to work with is everything in terms of whether the project can get off the ground, Moses later explained. The McComb voter registration drive would not have taken off without someone like Owens.

Too many discussions of “grassroots organizing” and “top-down versus bottom up organizing” ignore the lessons that are taught by Moses’ experience. Respected local leaders introduced him into the local communities in which voter registration projects started and asked the local community to financially support the work that Moses and other SNCC field secretaries were going to do. To the question, “Who sent you?” that might be asked of a SNCC worker, the answer was Webb Owens or Amzie Moore or CC Bryant or any of a number of respected local people who legitimized SNCC’s presence in their community.

Where that beginning legitimacy was lacking, the SNCC worker had to “earn the right to meddle” by gaining the trust of locally respected people. Field secretary Charles McLauren wrote a SNCC staff working paper on invited and uninvited organizers, and what the latter had to do to earn the trust that was the precondition for engaging local people in “Movement” activity.

An Organization of Organizers

Moses also recruited young people to become organizers and developed in them an understanding of the role that was controversial within SNCC. For Jim Forman, SNCC’s executive director, SNCC was an organization of organizers and itself a leadership organization, a “vanguard”. To use a spatial image, SNCC would be internally democratic as would groups it created, but it would be in front of a growing body of affiliates from across the south.

For Bob and his Mississippi full-time organizer recruits, SNCC was alongside. It was this understanding of the organizer’s role that created the space for people like sharecropper Fannie Lou Hamer to emerge as major Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party leaders. For the alongside organizer there is a continuing tension between, on the one hand, the greater vision an initial organizing effort offers and the belief in it that develops in its rank-and-file and secondary leaders, and, on the other, the egos and selfish interests that might emerge at various levels of leadership, and the realities of power relationships that necessarily force compromise upon the vision if it is to move forward.

The projection of local people led Bob to support the revival of the Council of Federated Organization (COFO), an umbrella organization in which the major civil rights organizations could develop a common strategy and implementation plan to break Mississippi’s iron wall of segregation. Under COFO’s auspices, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) was created. These were necessary steps to advance the cause, though a deep sacrifice organizationally for SNCC which was providing 90% of the full-time staff in the state and would no longer be able to raise funds in the name of its Mississippi Project. The sacrifice was necessary. That’s how Bob thought.

The Mississippi Summer Project

The idea of bringing the country to Mississippi was circulating in the state as early as mid-1963. Let America see Mississippi for what it is and surely it will reject it and demand change was the underlying premise. Moses was quiet during the increasingly intense discussion that followed. Local people generally liked the idea. Many of SNCC’s young Black staff feared what the presence of an overwhelmingly White, elite-college educated, group would do both to local leadership and to their own roles. The fears were legitimate, and Moses didn’t want to lend his weight to one or another point of view.

Then yet another murder of a Black local activist took place. Louis Allen, witness to the murder by a state legislator of local Black leader Herbert Lee, initially told a lie that made the murder appear to be self-defense. Allen changed his mind and told the FBI that he would testify. Explaining why, he said, “I did not want to tell no story about the dead, because you can’t ask the dead for forgiveness.” Allen was gunned down on his farm.

The Allen murder ended Moses’ silence. He threw his considerable weight behind the Summer Project.

Just before completion of training for the second group of summer volunteers, three more Movement people were murdered: a Black Mississippian and two northern White volunteers. Moses addressed the volunteers, inviting them to go home if the news of these murders created any doubts for them. The accounts vary as to how many left, and there may have been none, but it was fewer than the fingers on one hand.

Later, Moses said of them, “[I]t turned out they had within them, individually and collectively, some kind of moral toughness that they were able to call upon. And God knows they needed it, because it was not just the Mississippi government, it was also the issue that the space in the Black community was really not a completely welcome space. There were some elements there which were welcoming them and bringing them in as family…, but then there was this resentment also, so they had to figure out how to walk through that. It is to their everlasting credit that they did.”

The Algebra Project (TAP)

How The Algebra Project teaches algebra to its students who had been tracked out of studying math in most of the schools they attended remains a mystery to me. To say the least, algebra is not one of my strengths. Bob once said to me, “anyone can learn algebra.” When I challenged him to teach me, we gave up because our time for humoring me had run out—a meeting beckoned. The evidence is that those who thought they couldn’t learn it can!

What I do understand is some of its core concepts, and they are really organizing concepts: begin with people’s experience; tap into their curiosity; engage them and their families in the process; go step-by-step, establishing self-confidence and building from one experience to the next. TAP makes demands on those who would participate in it: you have to do extra studying, including a summer. And you have to make demands upon the education system. The element of demand is central. Change comes from below.

TAP is also more complicated than voting. School districts, superintendents and “downtown” math divisions, principals, math department heads, classroom teachers and others have to buy in. Bob’s organizing talent put together a national organization of school people, including university math departments, school superintendents and districts, school reformers and others to pursue its goals.

Across the country, in Black inner-city schools and in Appalachian hollers, TAP is working. It contributed an appreciation of social class to Bob’s thinking that I don’t think was previously there. In relation to their education, he told me he didn’t see much to differentiate poor White students in TAP classes in southeast Ohio and those in Black inner-city schools.

His Meaning To Me

Bob was closest to me in age of the three people who most influenced my life as a community organizer. (The others were political theorist/longshoremen’s union leader Herb Mills, my best friend for 60 years who died in 2018, and Saul Alinsky, who died in 1972, for whom I directed a Black community organizing project in Kansas City, MO 1966/1967.) Bob was born in 1935, two years before me. Like me, he grew up in a public housing project—he in Manhattan, I in San Francisco.

We first met when he came to the San Francisco Bay Area on a fundraising tour I organized as SNCC’s field secretary in the area. We got to know one another better when I worked out of the Greenwood, MS SNCC freedom house during the summer of 1963. Dick Frey and I were the first Whites to be assigned to the Mississippi Delta. I got to watch him work up close.

Our friendship renewed when Bob started traveling with The Algebra Project. He came to the Bay Area where I connected him with local community organizations that were interested in getting TAP introduced in their school districts. He invited me to come to Broward County, FL where the school district was adopting TAP as part of its curriculum. We developed a plan for an organizing project that would organize parents and their communities; unfortunately it never got off the ground.

In 2012, I organized a trip to the Bay Area by Bob to raise funds for the defense of Ron Bridgeforth, a former SNCC field secretary who’d gotten himself in trouble with the law when he used a gun to steal materials for a Black children’s tutorial program and got in an exchange of shots with a cop who was attempting to arrest him. (Bridgeforth escaped and went underground for 40+ years. We’d been friends before that incident when he was still a SNCC worker.)

Bob often stayed at my place when he came to the Bay Area. We got to have serious discussions about the things we cared most deeply about. I got to know him as a person.

What stands out about Bob is the quiet that surrounded him—a quality of serenity that made him a rock of steadfastness no matter what turmoil surrounded him.

We think of charisma as associated with dramatic speeches made to tens or hundreds of thousands: Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., John L. Lewis and other great orators. Bob’s charisma was different. He spoke softly, often using questions to get others talking with each other in small groups and listened carefully. But there was no question: when he was in a room, he was usually the center of attention.

For Bob, there were no nobodies. That created a deep bond between him and sharecroppers, day laborers, domestics and other otherwise nobodies in the dominant culture. The other side of this coin was that nobody intimidated him: not a Mississippi sheriff with a gun pointed at him or U. S. Senator Hubert Humphrey trying to persuade him of the honorary at-large two-seats “compromise” at the 1964 Democratic Party Convention.

Bob imagined a national constitutional amendment making education a right like voting and promoted the idea across the country when possibilities for ideas like that still seemed real. And he could return to a Mississippi classroom to teach his new algebra to make sure that it worked. The global and local were always interconnected in his theory and practice.

Bob, rest in peace. The country is a better place because of your presence. I miss you.

…

Wonderful tribute Mike. Thanks. You spoke of Bob Moses often through out the years. When I heard of his passing I immediately thought of you. My deepest condolences. – Rich Waller