The Biggest Bust Ever: Direct Action Lessons From Three Days in May of 1971

By Steve Early

Fifty years ago this May, when the U.S. Capitol police were better at arresting large numbers of white trespassers, I watched 1,200 of my fellow anti-war demonstrators carted off to jail for just sitting on the back steps of the Capitol and listening to speeches from two House members.

That bust was the last gasp of three days of mass protest activity, in Washington, D.C. over the Vietnam War. It resulted in the largest number of civil disobedience-related detentions in U.S. history—12,000 in all, including a record-breaking single-day total of 7,000 people arrested on May 3, 1971.

To conduct this unprecedented round-up—later found to be unlawful—President Richard Nixon deployed far more law enforcement and military personnel than the Trump Administration used, in the same city, last year. Organizers of the May, 1971 anti-war actions had publicly announced their intention to shut-down the nation’s capital–by blocking its streets, bridges, and buildings. But that plan was thwarted by nearly 20,000 local, state, and federal police officers, National Guard members, U.S. Marines, paratroopers from the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division, and the Sixth Armored Cavalry from Fort Meade in Maryland.

Last June, President Trump’s threatened response to Black Lives Matter protests in triggered a major debate about the appropriateness of deploying such active-duty military personnel against civilians, in DC or anywhere else. Push back from the military itself—and members of Congress– helped stay the hand of the Nixon fan then occupying the White House.

Meanwhile, intentional law-breaking— by police brutality protestors in some cities last summer and Trump supporters on January 6—was much condemned in the mainstream media. That problematic equivalency aside, the question of how and when to organize mass protests, that are militant and disruptive, while remaining as peaceful as possible, remains a challenge the left should not ignore—if only to avoid alienating potential supporters or community members adversely impacted.

Several excellent studies of the Mayday protests, including L.A. Kauffman’s Direct Action (Verso, 2017) and Lawrence Roberts’ MayDay, 1971 (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020), are worth consulting about these questions, on the fiftieth anniversary of the biggest bust ever. As Kauffman argues, Mayday “influenced grassroots activism for decades to come, laying the groundwork for a new kind of radicalism: decentralized, ideologically diverse, and propelled by direct action.” According to Roberts, the Nixon Administration’s response led to “consequential changes to American law and politics, including the rules governing protests in the nation’s capital, which remain in force today.”

A Grand Finale

In the Spring of 1971, Mayday was the grand finale of anti-war actions that included the bombing of a Capitol Building restroom by the Weather Underground; an occupation of the Capitol Mall by Vietnam Veterans Against the War, and a mass rally in April organized by the National Peace Action Coalition (NPAC), which drew 500,000 people. This last event was similar to the huge peace demonstrations held in Washington, D.C. on weekends during the Spring of 1970 and the Fall of 1969. Each involved bussing in large crowds of people, doing a little marching around, listening to speeches and music, and then getting back on the busses to go home. For some in the anti-war movement, this familiar routine—what one critic called “dull ceremonies of dissent” — began to feel futile and too easily ignored by the Nixon Administration.

The late Rennie Davis, the mastermind and maestro of May Day, had a different idea. Tens of thousands of activists would come to Washington ready to camp out and disrupt business as usual, on a weekday when thousands of federal workers were trying to get to their jobs. As viewers of Aaron Sorkin’s flawed film about ‘The Chicago Seven” know well, Davis was no stranger to confrontational protest. A leader of Students for a Democratic Society at Oberlin College, he helped organize anti-war demonstrations at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968. This made him a defendant in the most famous political trial of the era, resulting in a 1970 conviction for incitement to riot (that was later overturned on appeal).

Davis was still facing a five-year jail term for his Chicago Seven role when he courageously hit the road to convince campus activists that if “the government won’t stop the war, the people will stop the government.” As one old SDS comrade told the New York Times when Davis died, at age 80 in February, Rennie’s style of organizing involved a lot of “smoke and mirrors.” He believed in “political salesmanship, creating a kind of myth that wasn’t quite a lie but created an image of possibility, even if it wasn’t yet true.”

The game plan developed by Davis wasn’t an easy sell among traditional practitioners of civil disobedience or NPAC. Pacifist foes of the Vietnam war tended to play by strict non-violent protest rules; if you broke the law by blocking a federal building or burning draft board records, you didn’t try to evade arrest afterwards, for either misdemeanors or felonies. You sat (or laid down) and waited to be hand-cuffed and hauled away. NPAC leaders, following the Socialist Worker Party line, didn’t favor getting busted at all. They believed that the broadest possible anti-war movement could only be built through continued reliance on massive protests, that remained peaceful and legal. “When people state they are purposely and illegally attempting to disrupt the government…they isolate themselves from the masses of American people,” argued The Militant, an SWP publication.

Affinity Groups

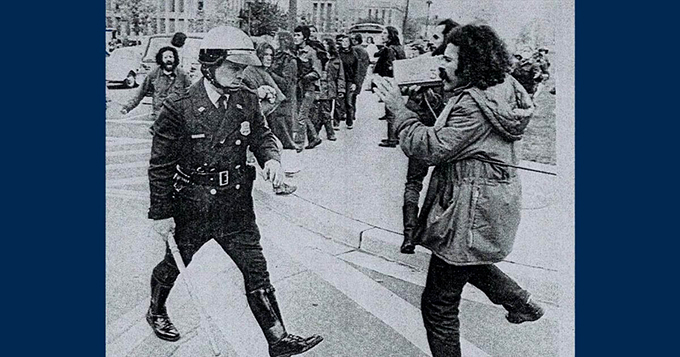

Ignoring such counsel, Davis and fellow members of the May Day Collective, envisioned widespread mobile civil disobedience. Protestors would come to Washington as part of small, home-grown “affinity groups” ready to disrupt and run, not damaging property or harming people but definitely trying to paralyze commuter traffic entering the District of Columbia on Monday, May 3, 1971. The staging area for this affront to public order was originally going to be Rock Creek Park. But, after negotiations with city officials, our short-lived official camping site became West Potomac Park, near the Lincoln Memorial. On May Day itself, Saturday, May 1, 50,000 people gathered there to hear a rock concert and last-minute pep talks. Among the bands playing that night were the Beach Boys, who insisted on being the opening act so, as co-founder Mike Love explained, they could leave “before any riots broke out.” Before we emerged groggy from our tents the next morning, several thousand DC police officers had surrounded the encampment and ordered its dispersal.

To avoid any premature confrontation, almost the entire crowd packed up, and left — seeking shelter in college dormitories, church basements, private homes or apartments throughout the city. By Monday, May 3, our numbers were greatly reduced but, by most estimates, still more than 25,000 strong. By mid-morning, few demonstrators had found their way to locations originally assigned to them in the “tactical manual” developed for the protest. But that didn’t matter because President Richard Nixon had stubbornly refused to give all federal employees the day off, to avoid rush hour traffic snarls. As protestors roamed downtown DC, dodging huge tear gas barrages, they created small barricades, left disabled cars in roadways, or temporarily blocked intersections with mobile sit-ins. As Roberts observes,

“The tactical advantage underpinning Mayday was now apparent, the asymmetrical warfare of a guerilla force against a standing army. It was nearly impossible to defend against small decentralized bands who could shift on a dime, tie up police or troops at one spot, and then get to another place before the authorities could adjust…”

One adjustment the authorities did make created a legal nightmare for them. DC Police Chief Jerry Wilson suspended the use of field arrest forms and accompanying Polaroid picture-taking that linked particular officers to individual arrestees. As a result, on May 3, nearly 7,000 people were detained, but with almost no information about who they were, what they had done, or who had arrested them. In addition to not being able to easily prosecute anyone nabbed in this fashion, the city quickly ran out of places to hold everyone. During my own 48-hours of detention, I never saw the inside of a jail cell, which was fortunate because they were dangerously overcrowded. Along with fellow detainees from Vermont, I was first transported, via paddy wagon, to the exercise yard of the DC city jail. Then several thousand of us were moved to the old DC Coliseum, an indoor sports arena, where members of the National Guard, bored but friendly, kept watch.

Conditions were not great but a lot better than protestors experienced, penned up over-night, in an outdoor practice field next to RFK Stadium. There, sympathetic members of the local African-American community showed up with much needed donations of food, water, and blankets that were passed over the chain link fence to detainees who were almost entirely white. One organizer of that relief caravan, civil rights activist Mary Treadwell, informed the press that she was there because anything that “can upset the oppressive machinery of government will help black people.”

Jamming the Jails

Even critics of our attempted disruption of the city—and there were many in politics and the press– soon expressed concern about the circumstances of our confinement and related militarization of the city. The use of mass preventive detention–which resulted in some non-protestors (including reporters) being swept off the street as well — paralyzed the local jail and court system. Creating that kind of crisis was very much in the tradition of free speech fights waged by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) a century ago or the civil rights protests which filled southern jails in the 1960s. In both situations, orchestrated mass arrests were used as a pressure tactic against local authorities interfering with the exercise of constitutional rights.

As word spread that our legal defense team was trying to persuade a federal judge to order an unconditional release, many detainees in the Coliseum spurned tempting offers to be finger-printed and released on $10 bonds. In the meantime, 5,000 fellow protestors, who had eluded the first day round up, descended on the Justice Department and Capitol Building on May 4 and 5, respectively. There, they sat down and got arrested in more traditional fashion. Among those hauled away was John Froines, one of two Chicago Seven defendants acquitted in that case, but now, along with Davis and Abbie Hoffman, indicted for conspiracy again, as a planner of Mayday.

In MayDay 1971, Lawrence Roberts, who became an award-winning journalist after being a detainee himself, provides a detailed account of the subsequent litigation, which continued for sixteen years. Only a handful of people were ever convicted of anything. The charges against everyone else were dropped, including the federal indictments of Davis, Froines, and Hoffman for conspiracy. “Over the years,” Roberts writes, “thanks to class action cases filed by the ACLU, as well as individual lawsuits, judges and juries awarded millions of dollars to thousands of detainees, for violations of their right to free speech, assembly, and due process…Congress acknowledged, in a backhand way, that the fault lay as much with the federal government as the police; it appropriated more than $3 million for the city to help defray the costs of settlements and damages.” In one jury trial, the plaintiffs initially won $12 million in damages, an amount later reduced on appeal.

As Roberts notes, key players in the suppression of Mayday ended up spending more time in jail, for more serious offenses, than anybody who blocked traffic to end the war in Vietnam. That’s because, 13 months later, Nixon administration operatives were caught burglarizing and bugging the Democratic National Committee, which had offices in a DC neighborhood where much Mayday skirmishing happened. The resulting Watergate scandal ended with Richard Nixon facing impeachment and forced to resign from the presidency in 1974. Among his various co-conspirators were Mayday crackdown architects like White House counsel John Dean, Nixon’s chief of staff H.R. Haldeman; his top domestic policy advisor John Ehrlichman; Attorney General John Mitchell; Assistant AG Richard Kleindienst, and White House staffer Egil Krogh. A future Supreme Court chief justice, named William Rehnquist, provided a Justice Department memo assuring Nixon that he had “inherent constitutional authority to use federal troops to ensure that Mayday demonstrations do not prevent federal employees from…carrying out their assigned government functions.”

It was the kind of green light that Donald Trump sought, but never quite got last June, when deploying the military against protestors in Washington, D.C. became a White House strategy again.

…