“A fascinating fight for a man’s place in our time”

By Ousmane Power-Greene

Book Review

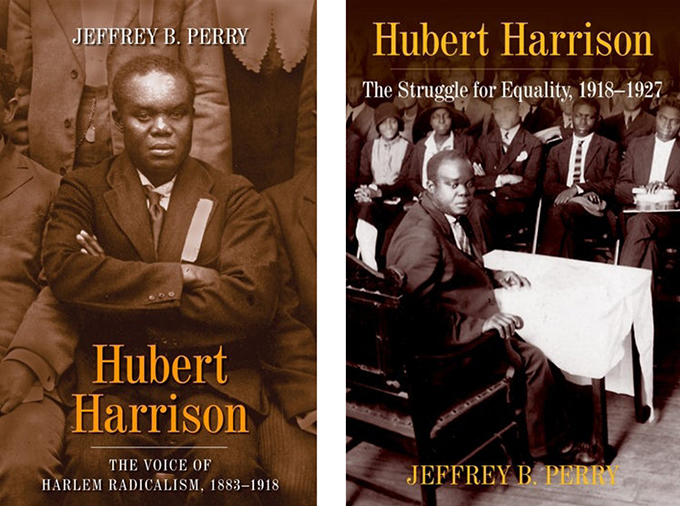

Jeffrey B. Perry, Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883 – 1918. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

Jeffrey B. Perry, Hubert Harrison: The Struggle for Equality, 1918-1926. New York: Columbia University Press, 2020.

.

As black socialist Frank Crosswaith once wrote, “The story of the New Negro’s fascinating fight for a man’s place in our time is the story of Hubert H. Harrison. And when the impartial historian writes the history of the black man’s bid for a square deal, he will be building, with the written word, a monument to Dr. Harrison which will stand for all time as a symbol of inspiration to the men and women of the Negro race as they move forward to positions of power, prestige and pride.” With the publication of Jeffrey Perry’s groundbreaking two-volume biography, Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism (2008) and Hubert Harrison: The Struggle for Equality(2020), scholars, activists, and community organizers have a study of the life and ideas of one of the most important black radical intellectuals of the twentieth century. For over forty years, Jeffrey Perry has been researching and writing about Hubert H. Harrison despite his marginalization among those scholars who research the New Negro movement or “Harlem Renaissance”. Thus, readers have only a glimpse of Harrison’s importance in works, such as Phillip S. Foner’s classic, American Socialism and Black Americans: From the Age of Jackson to World War II and Winston James, Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia: Caribbean Radicalism in Twentieth-Century America. Since 2000, however, Harrison’s writings and speeches have appeared in edited collections, such as Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Gene Andrew Jarrett, The New Negro: Readings on Race, Representation, and African American Culture, 1892-1938 (2007).

Simply put, Perry’s Hubert Harrison demonstrates Harrison is the key link between early twentieth century black radicalism and the Marxist tradition that shaped the ideological vision of leaders, such as Marcus Garvey and A. Philip Randolph.

“Harrison’s public criticism of Booker T. Washington brought the Wizard of Tuskegee, as Washington was known then, to use his influence to have Harrison fired from his job”

Born in 1883, Hubert Harrison immigrated to America from the Caribbean island of St. Croix as a seventeen-year-old orphan in 1900. Without much evidence about Harrison’s early life, Perry provides a thorough examination of the key events in the Danish Caribbean that influenced the young Harrison to leave his home for the United States. When Harrison arrived in New York in 1900, he entered a city where blacks were limited to menial jobs and lived in the worst tenements. The oppressive conditions blacks endured in Manhattan did not discourage Harrison, and he soon found his way to the lyceums at St. Benedict’s and St. Mark’s where he met other black working-class intellectuals such as John Bruce, a lay historian and journalist, and Arthur Schomburg, the legendary bibliophile and collector of African artifacts. Within this context, Harrison refined his oratory skills by overcoming a lisp and developed his ideas about the role of race and class in American history.

Eager to earn a living through his writings, Harrison published book reviews in newspapers, such as the New York Times, making him one of the earliest African Americans to do so. While Harrison’s intellectual gifts were apparent in his book reviews and lectures, he struggled to earn a decent living from his writings, and this forced him to seek other means to support himself. Harrison took a position as a postal worker in 1907, and Perry explains that such role was one of the best paying jobs for African Americans at that time. By linking up with fellow postal workers, Harrison joined a study circle to discuss, among other things, the challenges black people faced in New York City and the nation. In this context, Harrison found a satisfying space to develop his ideas and share his own historical work on the Reconstruction era, which he hoped to have published.

Harrison’s companionship with other black postal workers would end, however, when Harrison’s public criticism of Booker T. Washington brought the Wizard of Tuskegee, as Washington was known then, to use his influence to have Harrison fired from his job at the Post Office. As Perry recounts in startling detail, Harrison was fired for writing several letters to local papers that criticized Booker T. Washington’s statements abroad, which Harrison believed had downplayed African Americans’ plight in the United States. On the surface, it would appear that Harrison’s removal was a consequence of complaints he had made over an unjustified reduction of his salary, but, as Perry proves, Booker T. Washington’s friend Charles W. Anderson bragged about how he orchestrated Harrison’s termination in a letter to Washington in September 1911. By the end of the month, Harrison would be removed from his position at the Post Office, and this would cause turmoil for Harrison’s family, forcing him into poverty.

Although losing his job at the post office caused his family financial hardship, Harrison used this bleak circumstance to pursue full-time employment with the Socialist Party as a lecturer. Although there is tremendous uncertainty surrounding the date when Harrison actually joined the Socialist Party, Perry argues that it most likely happened in 1911 after he was fired from the Post Office. Between 1911 and 1912, Harrison became “Local New York’s foremost Black speaker, its leading Black organizer and theoretician, and the head of the Colored Socialist Club,” according to Perry (173). Yet, Harrison’s efforts to recruit more blacks into the Socialist Party were challenged, as Perry explains, by “conservative party leaders” who at the local and national level failed to adequately deal with the question of how to bring black people en masse into the Socialist Party, while changing white supremacist attitudes rampant among many of its members.

“We say Race First, because you have all along insisted on Race First and class after when you didn’t need our help.”

By the end of 1912, Harrison had gravitated toward the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) brand of socialism. Yet, when the Socialist Party rejected the IWW’s advocacy of a more militant politics, Harrison found himself, once again, at odds with party heads. In fact, Perry writes that, “Harrison found that support of his work by leadership of Local New York was waning,” (175) and this has been linked to W.E.B. Du Bois’s vocal criticism of Harrison’s quest to form socialist branches within predominately black New York communities. This ideological riff with those who supported Du Bois’s position would soon drive Harrison from the Socialist Party.

The specific circumstances surrounding Harrison’s departure from the Socialist Party surrounded his negative response to an Executive Committee command for him to forgo a debate with a well-known anti-socialist speaker named Frank Urban. Perry writes that “the ideological break, followed by the suspension, marked a major turning point” in Harrison’s life. Yet, this re-orientation away from the Socialist Party did not mean that Harrison renounced socialism, and Harrison continued to view himself as a socialist throughout his life.

Perry points out that Harrison’s break from the Socialist Party led him to focus on organizing African Americans in opposition to race-based oppression in the United States and abroad. Harrison’s shift from a “class first” position to “race first” position was distinct for this time period. In his oft-cited essay, “Race First versus Class First” Harrison explained: “We can respect the Socialists of Scandinavia, France, Germany or England on their record. But your record so far does not entitle you to the respect of those of us who can see all around a subject. We say Race First, because you have all along insisted on Race First and class after when you didn’t need our help.”[1] By 1915 he would become one of the leading New Negro radicals, coining the phrase “Race First,” and emerging as its most influential and visible leaders.

Over the next three years, Harrison provided black Harlemites with an unfettered voice that called out all who opposed militant action against racism in the court of public opinion. Harrison’s outdoor lectures established him as one of the most visible public orators, who, as his contemporaries pointed out, had earned near icon status for his “encyclopedic” grasp of a wide variety of social, political, and scientific topics. Those who listened to his soap box orations walked away enlightened, humored, and aware of a new strain of race radicalism that sought to include the masses, rather than a talented tenth, in the struggle for civil rights, political power, and economic independence.

In 1917, Harrison founded the Liberty League of Negro Americans and became the editor of its organ, The Voice. This organization was the first of its kind in Harlem, and Harrison used mass meetings and editorials in The Voice to call for “equal justice before the law and equal opportunity” regardless whether or not such demands bumped up against the social norms or powerful leaders. One of the organization’s central aims was to “Stop Lynching and Disenfranchisement in the Land Which We Love and Make the South ‘Safe For Democracy’” (282). The Liberty League boasted a broad array of African Americans from various backgrounds, political affiliations, and class positions. Several of the Liberty League’s most notable members were Marcus Garvey, Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Sr., and Madame C. J. Walker.

By 1918, Harrison’s influence had extended beyond Harlem and into a national arena. The Boston-based newspaper editor and racial agitator William Monroe Trotter (also a member of the Liberty League) found in Harrison an able ally in the struggle against white supremacy in America and throughout the world. Jeffrey Perry illustrates Harrison’s rise to national prominence through his role at the Liberty Congress in Washington, D.C. in June 1918. Attended by 115 delegates from 35 states, the Liberty Congress, as Perry explains, “was a precursor to the March on Washington Movement during World War II (led by A. Philip Randolph) and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom during the Vietnam War (led by Randolph and Martin Luther King, Jr.) (381). Those in attendance called on lawmakers to make lynching a federal crime, to enforce the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, and to compel the President and Congress to recognize the link between justifications for U.S. involvement in the war in slogans, such as “to make the world safe for democracy,” and the just treatment of African Americans who endured race riots, lynching, and discrimination. Having been nominated unanimously as president of the congress, Harrison now had a national constituency, and he used his platform to challenge the leadership of other African Americans, such as Du Bois’s whose “Close the Ranks” editorial in The Crisis magazine called for patriotism during the height of racist mob violence against black people in cities throughout the nation.

“With more wit and wisdom than Marcus Garvey, and deeper roots in the black community than Alain Locke, Harrison straddled white leftist intellectual circles and black radical street corner politics in ways that were unmatched by his contemporaries.”

Through Perry’s prodigious research we have a portrait of a committed man, unwavering in his struggle to eradicate racial prejudice in America and abroad, who provided others with a theory for race advancement in his time and for future generations. There were three pillars of Harrison’s efforts: First, a race consciousness rooted in a class consciousness that depended on community engagement. Second, the central role the black intellectual and critic in shaping the way black and white people interpreted literature and culture. Finally, a program, based in black communities, that approached the struggle for racial justice through an international lens. Perry not only documents in careful detail Harrison’s effort towards these ends, he shows the ways Harrison’s visibility within the Harlem community broadened his base of supporters.

With more wit and wisdom than Marcus Garvey, and deeper roots in the black community than Alain Locke, Harrison straddled white leftist intellectual circles and black radical street corner politics in ways that were unmatched by his contemporaries. Although A. Phillip Randolph, and Marcus Garvey had been known to criticize nearly all black rivals, these two giants of black nationalism and labor radicalism never committed one printed word of condemnation toward Harrison. Beyond activists, Harrison also earned the respect of white critics H.L. Mencken, playwright Eugene O’Neil, and black poets and artists often associated with the “Harlem Renaissance,” such as Claude McKay, Augusta Savage, and the actor Charles Gilpin.

Jeffrey Perry’s biography shows that Harrison was no closet intellectual, fomenting self-indulgent ramblings about racial injustice, the oppressive nature of capitalism, or the failure of the American dream. Always a man of the people, Harrison was in fact the consummate public intellectual, and for much of his life, as Perry explains, he remained dedicated to advocating in behalf of those who lacked power not for his personal benefit, but for the broader public good. As a public intellectual for and among poor black people, Harrison’s life has much to teach us about the dignity of working on behalf of those without jobs, political clout, or formal education. Whether lecturing on a Wall Street corner, or in Harlem, Harrison used his extraordinary intellectual gift to encourage those less educated to join in the conversation, to become informed, to be free thinkers, to agitate for rights, to stand up to so-called leaders and demand more. He called on those with power and influence to put aside pettiness, and to unite for a common cause.

Perry’s primary accomplishment, then, is that he presents readers with a thorough rendering of the Harrison’s life within a community of black and white activists intellectuals, striving to organize toward race and class equality. Not only does Perry’s biography chronicle Harrison’s efforts, it also places Harrison squarely within the major Progressive movements and New Negro Movement in the early twentieth century. Harrison’s broad array of admirers, from opposing political camps and various intellectual persuasions, attests to Harrison’s significance, and, indeed, as Perry shows in this excellent biography, his commitment to the struggle for equality made him the voice of Harlem radicalism.

Over the past five years, several other biographies of central figures of the early twentieth century, most notably Jeffrey C. Stewart, The New Negro, The Life of Alain Locke (2018) and Kerri Greenidge, Black Radical: The Life and Times of William Monroe Trotter (2019), have provided greater attention to figures who dominated the era often identified as the “Harlem Renaissance” or “New Negro Renaissance.” For this reason, Jeffrey Perry’s two-volume biography fits squarely within the context of revived interest in early black radicalism on the one hand and art, literature, and intellectualism on the other hand. Yet, Perry’s biographical treatment shows Harrison’s centrality within, and among, radicals, artists, intellectuals, who have come to understand this monumental Afro-American, Afro-Caribbean radical intellectual.

…

[1] Hubert Henry Harrison, When Africa Awakes, Baltimore, MD: Black Classic Press, 1997), 81.

This is an enlightening review of Jeff Perry’s works to bring Hubert Harrison to public attention and take his rightful place as a key figure in 20th century Black radicalism. Harrison’s writings and activism should be as well known as that of Garvey and Dubois, with real lessons for today’s struggles on the necessary connections between race and class. I look forward to reading Perry’s recently published “Hubert Harrison: The Struggle for Equality, 1918-1926.”