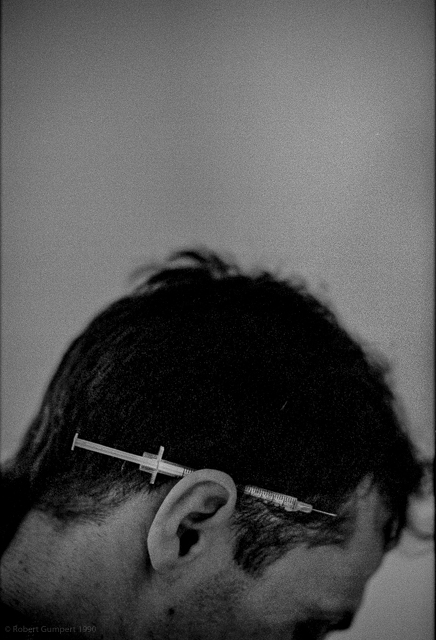

The War On Drugs

By Mike Miller

A review of Chasing the Scream: The Search for the Truth About Addiction. Johann Hari. Bloomsberry paperback, 2019.

Once upon a time, about 100 years ago, there was no war on drugs. They were legal. Most people who used them weren’t addicts. You could buy some of them “over the counter;” others were routinely prescribed by doctors. Then Harry Anslinger arrived on the scene and began working at the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. Beginning in the 1930s, he “did more than any individual to create the drug world we now live in.” Amongst other things, he’s responsible for the death of Billie Holiday. He is a despicable character. But Hari wants us to understand that Anslinger could only pursue his dark agenda because of a widespread darkness in human beings, a susceptibility to fear, a willingness to find explanations in devils when there are no facts to support them.

This book is personal. Hari’s partner was an addict, as were good friends and members of his family. He takes us on a journey of discovery to find out why “war” replaced acceptance and treatment. He documents the tremendous cost of this war—to those upon whom it’s waged, those who fight it who are themselves dehumanized in the process, and to the larger society that tacitly or explicitly supports it. His travels take him to slum neighborhoods in major cities across the globe, the Mexican border with the U.S., Uruguay, Portugal, Britain, Australia and elsewhere. He is on a determined search to get to the root of the matter—the original meaning of “radical.” Thus this is a radical book though not in the way the word is now typically used.

Hari’s sources are addicts and those who love them, politicians on both sides of the battle, scientists who justify and criticize prohibition, social workers, dealers, cops and anyone else who might shed light on his quest. Along the way, he travels extensively, digs deeply, and reflects carefully. I think the book is a model for anyone who wants to explain complicated things to a general readership.

The war on booze was waged in the U.S. during Prohibition. Its result was the creation of a whole underworld of gangsters, killing, corruption of politicians and more. It didn’t work. People who wanted to drink found a way to do so. Only now, because it was illegal, they decided if they were going to take the risk they might as well go for more potent stuff. Beer suffered; high alcohol content gained. Prohibition didn’t work. It didn’t diminish drinking. Yet despite the fact that prohibition of drugs was so similar a scenario, no one had the combined wisdom and clout to stop Anslinger and his Joe McCarthy-like crusade. It turns out he was a friend of McCarthy’s, and that McCarthy had a dirty little secret: he was a user!

This is what Hari concludes: people use drugs recreationally because they like it. They don’t become addicted. A much smaller number, who were damaged emotionally in some way—usually in childhood, use drugs to escape their pain. It is the pain that is the source of their addiction, not the heroin, cocaine, crack, marijuana or whatever is their preferred escape hatch. Some fraction who use the chemically most potent of the drugs may become physically addicted, but it’s not hard in the right circumstances for them to quit.

Hari also introduces us to the politicians and public interest groups that are fighting to make drugs legal. Portugal was the first nation to do it. Cities across the world have done it. Now several states in the U.S. have taken the first step by legalizing marijuana.

You will meet some incredible people in this book; you will enjoy meeting them. They are the ones who are fighting for peace. They range from former addicts to major political leaders.

There are tragic stories as well. Billie Holiday’s most of all, though the fate of young people who get sucked up into drug gangs is a close runner-up.

The cure to addiction, Hari argues, is connection. That’s right. Not medication but meaningful relationships that provide support, community and purpose in people’s lives. Here I think he misses an important distinction. Most of his examples are programs in which health professionals, social workers or former users become support people for addicts. This is the normal provider-client relationship at its best. Its practitioners are fantastic human beings.

But connection has another dimension. In the coal mining counties of West Virginia where Hari goes to look at the widespread abuse of opioids, there were meaningful, well paying, jobs. Men who did the work were part of a powerful union that asserted, defended and extended their rights and benefits. Workers were part of an occupational community, the creation of both their isolation from others and their interdependence on the job. They were deeply connected. That’s what good organizing creates and good popular organizations provide. I wish Hari had given more attention to this.

Read this book! You will learn from, enjoy, and be inspired by it.

…