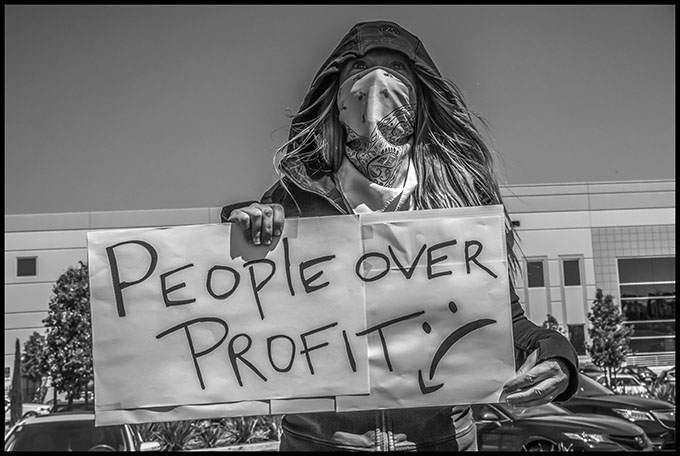

WORKERS’ STRIKES ARE AN IMPORTANT PART OF TODAY’S MOVEMENT

By David Bacon

There have been over 800 strikes since the coronavirus crisis began, according to Payday Report, with many especially since the murder of George Floyd. Regardless of the exact number, it is clear that something new is developing among workers.

There’s a lot of variation in these actions. Some have been protests, like those at Amazon, over the death of workers and lack of PPE. Some, like the strikes in the apple sheds in Washington, have been demands for safe work and compensation. Some have been protests over racism and in solidarity with Black Lives Matters.

These strikes don’t compare in size or number with the outpouring of rage over the murders by police, which have been enormous and ongoing. But they are very significant for a number of reasons.

They are class-based protests by workers, over the underlying conditions that have brought people into the streets in general. Overwhelmingly they have been organized by workers themselves, indicating both a deep level of anger over the conditions, and an understanding that striking is an effective form of protest and a means to change them.

In most cases unions have been slow to respond and overly cautious about action at the workplace. There are important exceptions to this, however. Familias Unidas por la Justicia, the new farmworkers’ union in Washington, immediately sent organizers to support apple shed workers who struck against the virus. The achievements of those strikes was the result, not just of spontaneous action, but of FUJ’s ability to organize support for them.

The longshore union organized a one-day strike and mass demonstration on Juneteenth, using the day celebrating the official end of slavery to mobilize support for dismantling police departments. Other unions locally and elsewhere have organized labor marches supporting Black Lives Matters as well. Bus drivers in Minneapolis refused to drive busses to transport police to demonstrations, or people arrested in the protests.

These strikes and actions show an intersection between the impact of the coronavirus and the protests over the murder of George Floyd. The actions against the virus and its impact, and against police murders, are clearly responses to a deeper social and economic crisis.

All these protests focus on a growing race-based economic inequality, especially impacting Black people. In the first twelve weeks of the coronavirus crisis, the combined wealth of all U.S. billionaires increased by more than $637 billion. The top 12 U.S. billionaires have a combined wealth of $921 billion. The entire value off all the homes owned by Black families, over 17 million households, is less than that.

This inequality isn’t a result of bad policies. It is historically and structurally part of American capitalism itself. The system has been built on the exploitation of all workers, but the super-exploitation of Black workers produced extra surplus value. Slavery and the exploitation that followed produced U.S. capitalism’s extraordinary growth.

That extra exploitation imposed permanent conditions of inequality on Black people – in jobs and wages, services, social benefits, and education. Today it is the basis for the racist impact of the coronavirus. The inequality imposed during slavery became the model for social inequality imposed on other racially and nationally oppressed people.

Race more than anything else determines who will live in crowded, segregated neighborhoods, who will be exposed to lead-poisoned water and toxic waste, and who will live with polluted air and suffer illness from asthma to heart disease. It is no surprise that when a new disease arrives, COVID-19, these same factors determine who will be the most affected in large numbers.

For every 100,000 African Americans, 62 die of the virus, 36 of every 100,000 native people, 28 of every 100,000 Latinos, and 26 of every 100,000 Asian Americans and every 100,000 white people.

While 70% of the people who die from COVID-19 in Louisiana are Black, Black people are only 33 percent of the population. In Alabama, 44 percent of the COVID-19 deaths are of Black people, who are 26 percent of the population.

… calling them essential means that employers can fire them if they don’t come to work. It does not require employers to pay them extra, provide health benefits, or pay them if they get sick and can’t work.

The coronavirus has created a crisis of unemployment for all workers in the U.S., but especially for Black workers, and workers of color generally. As of late May, 38 million people had lost their jobs during the pandemic, and the overall unemployment rate was 13.3%. A year earlier it was 3.6%. But Black unemployment was 16.8% (a year earlier 6.2%) and Latino unemployment was 17.6% (a year earlier 4.2%). Over 44 percent of Black households have suffered a job or wage loss due to the pandemic, and 61 percent of Latino households.

The government’s response to economic crisis has been to create the category of essential industry, and therefore, of the essential workers who labor in it. It is true that some kinds of production and economic activity are essential for survival. But the real-life result of calling people essential is that they are forced to work at a time when they are risking their lives.

Farmworkers are just one example. Their work is socially necessary, but calling them essential means that employers can fire them if they don’t come to work. It does not require employers to pay them extra, provide health benefits, or pay them if they get sick and can’t work.

Half of all farm workers are undocumented and excluded from the Federal CARES Act benefit package intended to help people survive the crisis. By denying any alternative means of buying food and paying rent the Federal legislation was an important pressure forcing them to go to work.

Trump forced Black and immigrant workers to go to work in meatpacking plants when the virus was everywhere by denying them unemployment benefits. He used the Defense Production Act to announce that nothing could get in the way of food production to ensure that meat would continue to be available in supermarkets.

The hypocrisy of this announcement was revealed when meatpacking companies admitted that in April, as the coronavirus crisis was raging, they exported 129,000 tons of pork to China, the highest amount in history.

About 37.7 percent of Black workers work in essential industries, compared to 26.9 percent of whites. They leave home to go to their jobs because they cannot stay home and work on computers. In California over half of essential workers are low wage workers, and are Latino or Black, including farmworkers, healthcare workers, custodians, building cleaners and truck drivers. Half of all immigrant workers are essential workers.

And because workers of color are concentrated in the essential categories, they are the ones exposed to the virus. At least 333 meatpacking and food processing plants, and 46 farms have confirmed cases of COVID-19. At least 32,099 workers have contracted it. At least 109 have died.

One company, JBS, has had a wave of infected workers and deaths. A black Haitian immigrant, Enock Benjamin, died in a Philadelphia plant where he was the union steward. Tin Aye, a Burmese immigrant and grandmother, died after working in a JBS plant in Colorado for ten years.

The impact of the virus is a terrain of social struggle. Meatpacking alone has seen a wave of protests and strikes. In mid-June JBS workers and supporters marched in the streets of Logan, Utah, demanding it close its Hyrum plant for cleaning and pay during the coronavirus outbreak. Some 287 workers from the plant tested positive for the virus.

In Stearns County, Minnesota, a protest outside a plant was organized by the Greater Minnesota Worker Center and the Council on American-Islamic Relations. In Springdale, Arkansas Venceremos, a poultry workers’ rights organization, tried to deliver a workers’ petition to Tyson managers.

Meatpacking workers protested outside Quality Sausage Co. in Dallas after some died. The wife of one worker said, “The virus was the gun that killed him, but Quality Sausage was the hand that pulled the trigger.”

These worker strikes and protests are part of a broader movement led by African American organizations responding to police murder and racial inequality. One of the most important organizations leading it is the Poor People’s Campaign led by Rev. William Barber and Rev. Liz Theoharis. It has a program with five basic demands:

- Establish Justice and End Systemic Racism – Democracy and Equal Protection Under the Law

- The Right to Welfare and an Adequate Standard of Living

- The Right to Work with Dignity

- The Right to Health and A Healthy Environment

- Cut the military budget

The campaign’s statement of principles says, “We know that poor and dispossessed people will not wait to be saved. Instead, people are taking lifesaving action borne out of necessity to demand justice now … We are demanding voting rights, living wages, guaranteed incomes, health care, clean air and water and peace in this violent world.”

These demands help to give a framework of radical reform, on a national level, to the individual demands put forward in the strikes and protests. In particular, they reiterate the thinking of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King in his speech condemning imperialism and war, when he charged that the bombs dropped on Vietnam were exploding in U.S. cities.

In the language of the Poor People’s Campaign, “if we cut military spending, implement fair taxes, cancel the debts of those who cannot pay, and invest our abundant resources in demands of the poor — we could fundamentally revive our economy and transform our society.”

.

This is a presentation made to a webinar organized by the Economics Faculty of the National Autonomous University of Mexico on June 24

…