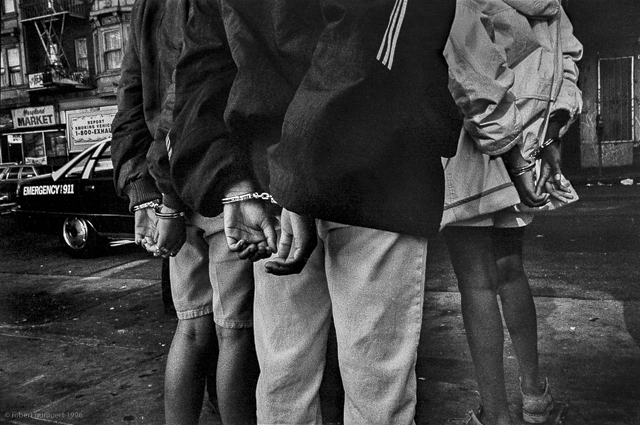

Cops in Our America

By Gary Phillips

“Cops” has been canceled in the wake of criticisms of the fictions this supposed reality show created in its years of heavily edited ride alongs with street cops. Several years ago the show had previously been canceled but was picked up by Spike TV, a “young adult male” oriented network at the time – which had aired such fare as a cartoon superhero called “Stripperella” and a lot of reruns of the “A-Team,” in 2013. Spike TV eventually became the Paramount Network.

It’s telling the then beleaguered Los Angeles Police Department in 1994 agreed to have the Fox originated show video their exploits. This was two years following the conflagration seen around the world post the acquittal on criminal charges of the four LAPD officers who, among other law personnel, viciously beat speeding motorist Rodney King. If surreptitious video could damn the police, then possibly edited footage could reframe them. Rebrand them. An outcome various departments sought when partnering with the program over the years.

“Cops” was always on somewhere, 15 to 20 times a day. Dan Taberski and producer Henry Molofsky and their screeners watched 846 episodes, about 86% of the shows. They collected 90,000 data points doing a deep data dive. The result was the six-part podcast “Running From Cops” that included interviews with “Cops” creator John Langley, the cops who appeared on camera and even a few of those who’d been arrested.

The most revealing though were the results of all that viewing and number crunching. Two percent of traffic stops in the real-world end in arrest. On the show, it’s 92% of the time. “Cops” portrays almost four times as much violent crime as occurs in reality, three times as much drug crime, and 10 times as much prostitution. Significantly the police on “Cops” became more effective in policing. In the second season 61% of the segments ended in arrest. By season 30, it was 95%.

“Basically, it presents a world that is much more dangerous than real life,” Taberski said, quoted in an L.A. Times article in June 11, 2020. “It presents the police as being much more successful than they really are. It misrepresents crime by people of color — the raw numbers are about the same but the show front-loads crime, and especially violent crime, by people of color.”

The flipside of the “Cops” narrative, putting you in the driver’s seat as it were, can be had in the virtual reality prototype Our America. Bryant Young is the game’s creative director and a game designer graduate from USC. He was recently interviewed by A Martinez on the “Take Two” program on KCRW. When you slip on your VR headset, Young related, you are a middle-aged, middleclass black father taking his kid Malcolm to school. There are several interactions with you and your son during this bright and sunny morning as you start the car and head out.

In talking with Malcolm, you find out the reason he’s intentionally missed the bus is because he’s getting racially name called at school. Trying to deal with that, your boss calls on the hands free and is pissed. The father is already late for work to do a presentation he’s supposed to be leading. He continues to give you as the unnamed father grief to ratchet up the pressure. As you’re driving the familiar blurt of a police siren is heard and in the rearview is the blare of the red and blue lightbar. What infraction did you commit the driver speculates.

Pulling over, Young continued, there’re always four choices you’ll be able to make at any given juncture in the game. He categorized them as some that black people will do, some that black people might think to do and two others are traps, to get you to say what you would not be able to say if you were black. Ominously he added a good outcome was being arrested as opposed to the various ways the driver could wind up being shot.

On Our America’s website, the designers note: “Virtual reality is an incredible tool for allowing people to view the world through a different perspective. We seek to use this technology to help people understand the fear, intensity, and helplessness of these situations that Black people must deal with every day.”

Here’s to a day when the norm is not fear and intensity that a black person has to feel when stopped by the police.

…