Planting hope amid a plague

By Sonnie R. Clahchischiligi and Photos/Story by Don J. Usner - Searchlight New Mexico

This is the first in Searchlight New Mexico 5 part series that “chronicles the impact of COVID-19 on five New Mexico towns. The co-editors of the Stansbury Forum urge you to explore Searchlight New Mexico for stories you just won’t be seeing or reading many other places. We appreciate them allowing us to repost this piece.

.

Older generations on the Navajo Nation have passed down stories of scourges, resilience — and survival. New generations are bringing the tales to life.

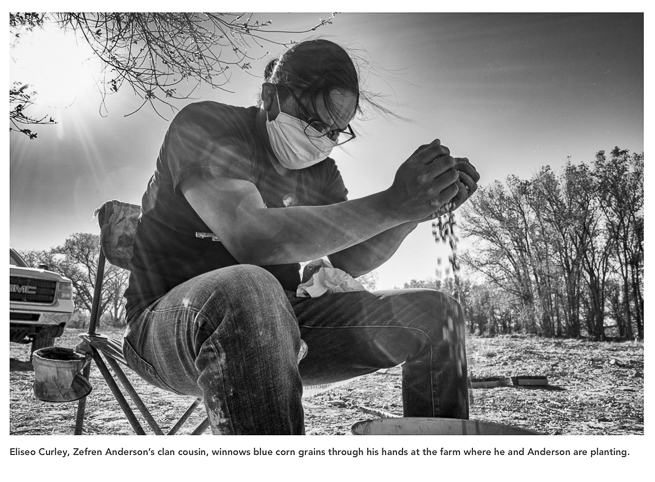

SHIPROCK, N.M. — Four miles down Farm Road, just off U.S. Route 491 in northern Navajo, a group of young Diné used what was left of daylight in early May to plant onions and potatoes on Yellow Wash Farm.

As the novel coronavirus stretched its way through Navajoland, leaving a trail of heartbreak and uncertainty, the four Navajo men, a mixture of family and friends from Shiprock, picked up their seeds and broke the earth with their shovels.

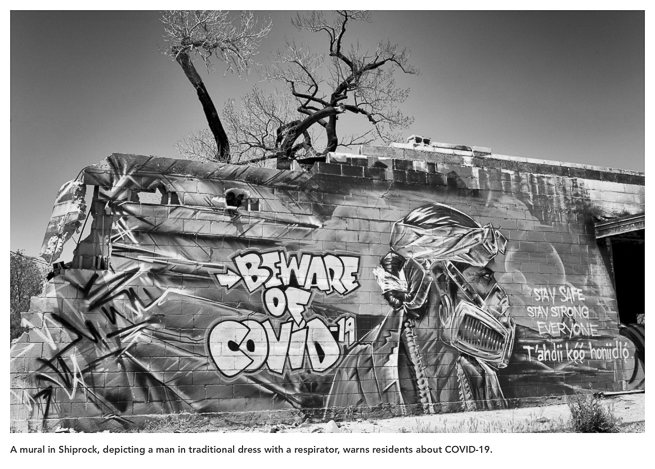

By month’s end, the Navajo Nation would have the highest per-capita infection rate in the country, surpassing even New York state. The outbreak cut a swath across the vast reservation, from outposts in Arizona to the mesas and high desert in northwest New Mexico, where Shiprock, or Naatʼáanii Nééz — the largest Navajo community — became a hotspot seemingly overnight.

Zefren Anderson, one of the farmers, was among hundreds of Shiprock residents who’d been tested for COVID-19; today he was awaiting the results.

But amid all the anxieties, the men felt a sense of purpose. They had the land to tend to. They were planting, because that’s what their family stories told them to do.

“If the stores close tomorrow, we have a backup plan. We have enough to survive till winter for whatever we’re creating on the farm,” Anderson said, taking care to stand six feet away from the other farmers. “We’re hedging our bets.”

There is no safe haven today on the Navajo Nation, where generations of families have lacked running water, food, electricity, indoor plumbing, safe housing and access to health care — the basic necessities for fighting disease. As of June 1, the Navajo Nation reported 5,250 positive COVID-19 cases, 1,745 recoveries and 241 deaths. In the Shiprock area last month, three siblings who buried their mother, father, and brother were forced to watch the burial services remotely because they, too, were infected with the disease.

Guidance from the past

While the staggering numbers have left many feeling hopeless, some in Shiprock have found solace by looking to history, traditions and family stories to push back against the pandemic. They are returning to a way of life depicted in tales passed down by elders, generation after generation.

Anderson, 38, a weaver and self-proclaimed family historian, found the blue corn and cantaloupe seeds his late grandmother left behind and started planting to prepare for a potential food shortage. He changed his weaving style from large, time-consuming museum works to simpler, utilitarian items: blankets, winter clothing and small pieces that he can trade for food or supplies.

He grew up hearing the old stories from his paternal grandparents. He revisited the tales his late grandmother told him about the early 1900s, when his great-aunt survived the 1918 flu pandemic. Thousands of Navajo were lost to the flu and other scourges. The Diné learned to fend off the plagues by practicing social distancing, washing their hands and whispering with their heads down to keep outbreaks from spreading. They learned to leave supplies for families and neighbors at the gates of their homes.

“Shiprock was always the epicenter for big disease outbreaks in the last 100 years — the Spanish flu, different types of lung diseases, meningitis,” Anderson said.

During the 1918 flu, some in Shiprock were so afraid of spreading the virus that, if they knew they were dying, they boarded up their families in their hogans, the traditional Navajo homes made of mud. A boarded up hogan — or hook’ee ghan — alerted other Navajo to stay away.

Tooh (water)

The people of Shiprock, or Tooh, meaning water, were mostly farmers and sheepherders, connected to the land, to the San Juan River that runs through it, and to Tsé Bitʼaʼí (winged rock), the famed Shiprock pinnacle whose existence is explained in Navajo creation stories.

Because early homes had no plumbing or running water — a problem that continues today — children typically got a bath only once a week. Anderson heard stories about crude washing machines that arrived by wagon in the early 1900s and a linen service that appeared in Shiprock, making it easier to clean bedding and clothes.

Handwashing, he recalled, was strictly enforced. “When I lived with my grandma, anytime I came in from outside the first thing she told me to do was to wash my hands.”

Grandmothers had learned about handwashing during their own childhood, when they heard chilling stories from elders about the 1918 flu. “We’re here because they did that” — they washed hands, he said. “And the people who didn’t, aren’t. It’s the same thing that’s happening right now.”

Anderson’s own prevention efforts have been fierce. He shaved his head after learning from a medical journal that the coronavirus can live on a strand of hair. He wears a full-length homemade lab coat when he leaves the house, an added precaution he takes because he lives with and cares for his father, a stroke victim.

To make sure he was healthy, Anderson also got two COVID-19 tests. The results of the first test came back negative.

To make doubly sure, he got tested again in May. The results arrived shortly after the day of planting with the trio of farmers. This time, he tested positive.

“I’m surviving,” he wrote in a recent Facebook post. He has been able to stay home, surrounded by his yarn, fighting off fever and a COVID brain fog. “I was ready to go if it was going to be my time,” he wrote. “But apparently there are more weavings to be woven and more fields to be planted.”

Fighting to save lives

Right now, as Navajo Nation Attorney General Doreen McPaul describes it, “the Navajo Nation has been devastated by COVID-19.” Communities lack resources at every level. “We are literally fighting for dollars to save lives,” McPaul said in May.

National and international media have descended to tell the story. Actor Sean Penn spent days on the Navajo Nation to offer help from his nonprofit Community Organized Relief Effort. Mark Ruffalo collaborated with Navajo entertainers to launch a grassroots response. A Game of Thrones star sent more than 1,000 cases of water to the reservation, where 30 percent or more households lack running water for drinking or washing hands.

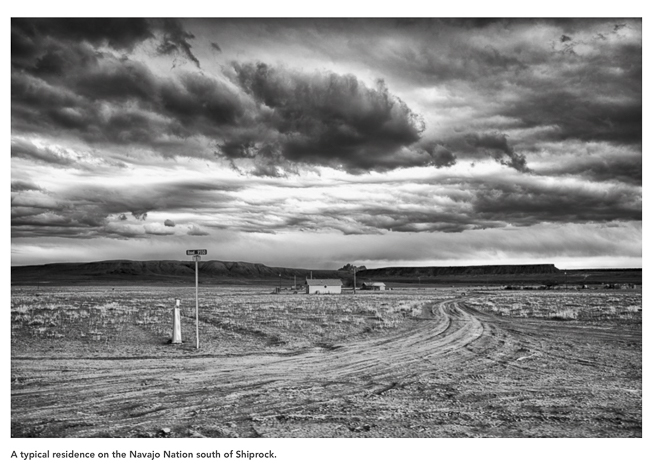

But the needs in Navajo Country run too deep to be solved with celebrity fundraising. The reservation’s roughly 175,000 residents lack health clinics, hospitals, schools, roads, broadband access and housing — things that the federal government is sworn to provide but has flagrantly refused to address. The U.S. is obligated by treaty to protect the nation’s health and welfare. It has ignored the responsibilities for more than a century.

Shiprock, in many ways, is more fortunate than other chapters, as the communities are known. With an estimated 8,300 residents, it is the reservation’s largest chapter, home to the Northern Navajo Medical Center, an Indian Health Service hospital with an emergency room and a handful of ICU beds. (Elsewhere, the nearest 24-hour hospital might require a four-hour drive across terrain too rough for an ambulance.)

Shiprock is also home to a branch of Diné College, a commuter campus that’s now mostly empty, aside from the parking lot. Students drive there to use the wifi, which many don’t have at home; others have had to drop their classes because they don’t have laptops.

Thirty to 40 percent of homes on the Navajo Nation don’t have basics like electricity, indoor toilets, cell phone service or computers, studies show. Most people get their information from local radio stations, including an all-Navajo channel that broadcasts in Diné.

Many of the 110 chapters are so remote, they’re little more than a scattering of mobile homes along treacherous dirt roads. Shiprock, by comparison, has a grocery store with fresh produce (a rarity) and a few fast-food restaurants. A series of potholed streets pass as a downtown, marked by a fairground, vacant lots, boarded-up buildings, a small shopping center, and a few local businesses that have survived for generations. One hamburger shack opened in the days when customers arrived on horseback.

Today, most residents live in government housing and in the hills beyond town, in overcrowded homes and singlewides; many generations of a family live together, sometimes along with friends. Doubling up is a way of life in a place where there is too little housing. An open-door policy is part of tradition.

Anderson’s home was also open to extended family. He believes he might have been infected by a relative who had contact with a healthcare worker, a viral daisy chain he never could have predicted. He is relying on family and friends to drop off supplies and food. As in the old days, they are leaving them by the gate.

Seeds of the past

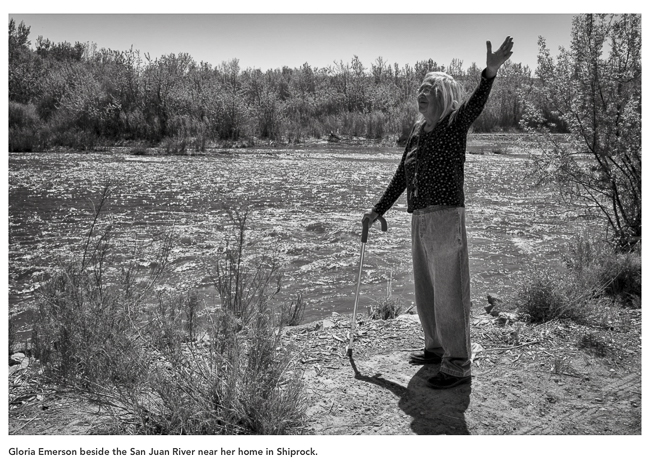

Just south of Yellow Wash Farm, Gloria Emerson, 82, shuffles toward a pile of red bricks tainted with graffiti, at what was once known as the Bureau of Indian Affairs compound. The bricks are all that is left of the apartment she once shared with her parents on the top floor.

Adjusting her ill-fitted cloth mask, the artist, writer and advocate points to the rubble and talks about her memories of the Shiprock that once was.

After graduating from high school, Emerson left Shiprock to get a college degree. She returned home and worked in social services on the Navajo Nation, launching an expansive career devoted to education, art and Navajo communities. She attended Harvard University, where she received a master’s degree in educational administration. She returned to Shiprock again in 2000, to help her aging parents.

Emerson eventually took over their farm in east Shiprock at mile marker 31, the last farm before leaving the reservation. She planted corn, melons and alfalfa when she could. This season, she had to hold off due to the pandemic.

“There’s a lot of beautiful memories here,” she said. “I always thought Shiprock represented the love and passion for the river and planting.”

The BIA compound where she grew up once looked like a mini college campus, with administrative offices around a quadrangle of lawn and trees. She spent her childhood along the San Juan River, admiring trees and flowers that created a safe haven. The BIA assigned garden plots to residents, encouraging Navajo people to plant.

But as the old Shiprock decayed, so did its relationship with the federal government. Washington historically has refused to address the reservation’s crumbling infrastructure and health disparities. At least one in five Navajo has diabetes. Heart disease and cancers are widespread, due to entrenched poverty, subpar health care, a scarcity of healthy food and contamination from uranium mines, among many ills. Government foot-dragging is endemic.

“They’re incredibly slow, and it’s not just the BIA, I think it’s the Navajo tribe, the chapters — there’s something very wrong with the way we’re governing ourselves,” Emerson said.

The pandemic laid bare the problems. The Navajo Nation waited six weeks before receiving the federal aid promised in the CARES Act, signed by President Trump in late March.

The tribal government finally got word in early May that it would receive a portion of its rightful $600 million. The Navajo and more than a dozen other tribes had to sue the federal government to get the proper funding in the first place.

“It’s shameful that the first citizens of this country are having to fight over and over for what is rightfully ours,” Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez said.

The delayed aid left people scrambling for already scarce supplies of water, soap, food, propane, personal protective equipment and other essentials. During the weeks of waiting, the number of positive cases on the reservation skyrocketed.

Emerson despairs at the destruction the virus has caused, and the lives lost. One of the few remaining members of her family, she spends most of her time alone, isolated on the farm.

Once long ago, she recalls stopping in her car to pick up an elderly woman along the road. The woman spoke very little except to say in Diné that where she was going was not that far. Emerson ended up driving the woman for more than an hour into the Arizona side of the reservation, where she lived.

“I just felt so bad when I saw how isolated she lived and no one there to help her … and then I remembered that’s the case with so many of our people,” Emerson said.

“I can’t stand being here isolated — I can’t stand it,” she added, suddenly overwhelmed. “It’s so hard to see and to have our relatives go on.” She misses the old days, the bustle of Shiprock, the company of other people. How could this have happened so quickly? she wonders. “A lot of it is, I think, that our people just don’t understand the dangers, and a lot of us just ignored the early signs. But it’s hard for me.”

Sidelined warriors

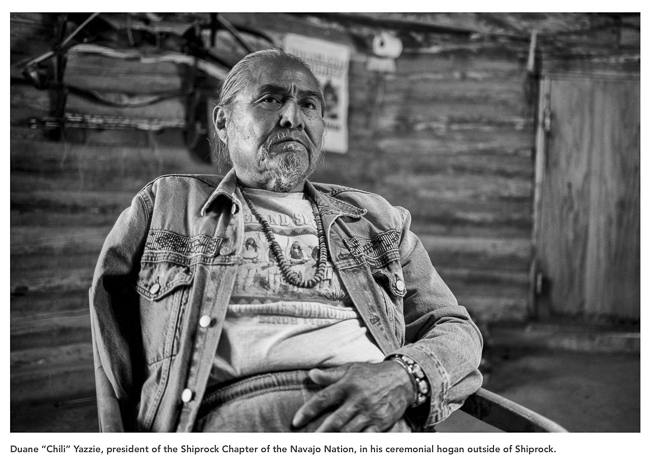

Early May mornings were still too crisp for Duane “Chili” Yazzie to tuck in the first seeds of planting season in his farm near Ditch Number Eight. Yazzie, 70, who is in his third term as Shiprock Chapter president, has spent every day at home since March 30, when the Navajo Nation stay-at-home order was put in place and tribal government offices closed their doors.

He can’t remember the last time he was sidelined or the community shut down. “Never,” Yazzie said, sitting in his family’s hogan, used for ceremonial purposes. “It never happened.”

The only disaster that comes close, he said, was the Gold King Mine spill in 2015, which contaminated the river with such huge amounts of toxic waste that the water turned yellow. Even then, Yazzie was able to walk into his office and come up with solutions.

Today, with government offices closed, he’s had to learn to work from home, trying to protect a community from a mostly unpredictable virus. A recent hard-fought battle with pneumonia also prevents him from going to his office; it permanently affected his lungs and puts him at high risk.

Planting gives him time to think.

“For the first time in a long time I’m a farmer again. It’s always been my therapy,” he said, gazing out the window toward his fields. “As a community leader it’s overwhelming to know that there’s very little that you can do proactively to prevent or mitigate the impact of the virus. We’ve just been scrambling around doing what we can, trying to keep people from not going hungry and making sure they’re OK.”

The virus has left people feeling paralyzed. They are supposed to stay home, but they’re at risk when they’re inside, crowded next to generations of family members who might have the virus and don’t know it. They’re afraid to leave home but have to: They need to get water, food and medicine, and take care of sick relatives.

There are grimmer problems, as well: Those whose loved ones die are forced to speed up the mourning process or scratch it altogether. Funeral services are in disarray.

At one recent service, only five family members were allowed to attend, including women who had to carry the heavy casket, typically a job for male relatives of the deceased. The funeral home sent no one to the gravesite to help.

Funerals are expensive, furthermore, and funeral homes are known to take advantage of the grieving, who can end up agreeing to services and expensive caskets they can’t afford. People can ask the tribe for financial help. But the funeral dispensations are often too small to cover all the needed services.

Some family members end up doing things like dressing the body and driving the casket to the grave themselves. Worse, those who go to funerals aren’t allowed to hug each other for comfort: They’re expected to grieve at six-foot distances.

Chapters are like large families; almost everyone is connected by friendship or kinship. That means almost everyone in Shiprock knows someone who has struggled with COVID-19 or died from it. Each day can bring a new round of worry, grief and fear.

An equilibrium upset

Yazzie refuses to give in. And he keeps searching for solutions. He knows, for example, that the most vulnerable people — the elderly — don’t speak English and don’t have the internet or social media to turn to for the latest news and instructions. So for them, he prepares a recording that explains safety precautions and relief efforts in Diné, the Navajo language. He sends it to the local radio station to play throughout the week.

To address local worries about dwindling food supplies, he encourages people to return to farming, canning and traditional ways of storing food. Yazzie also helped initiate the Northern Diné COVID 19 Relief Effort, which distributes food and supplies in Shiprock and the surrounding region, the Northern Navajo Agency.

The Northern Agency is often forgotten by the tribal government, he said, so the group took it upon themselves to respond. “Shiprock has always had that kind of resilient spirit that calls for independence,” he explained. “Our people have always been warrior people, all through the years.”

It’s been a time of great reflection, of trying to understand why this is happening, Yazzie said. He’s come to one conclusion that he’s heard traditional Navajo concur with: The world is in a great disorder; the equilibrium of the Earth is greatly upset.

“Perhaps the pandemic is the great discipline whip of the Earth, from having irretrievably damaged the Earth,” he said, and paused to search for the right words. “This virus is a force to be reckoned with,” he offered. “It is alive with death.”

…

Pingback: test

Pingback: MORE U.S. DEATHS IN COVID-19 PANDEMIC THAN IN WORLD WAR I – The Greanville Post

Pingback: More U.S Deaths in COVID-19 Pandemic Than in World War I