TWO DECADES AGO, MEXICO’S HUGE UNIVERSITY STRIKE DEFENDED FREE TUITION AND ACCESS

By David Bacon

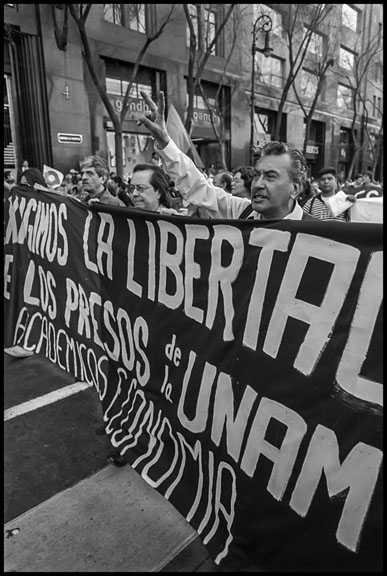

Historic photographs of Mexico’s huge protest over the arrest of students and the invasion of its premier university – all photos David Bacon

Twenty years ago Mexico’s Federal government moved to end the huge student strike at the National Autonomous University (UNAM). The strike, which began in 1999, reverberated far beyond Mexico. Like the WTO protest in Seattle, which took place at the same time, it became a global symbol of resistance to pressure by international financial institutions for austerity policies and the privatization of public services.

Social protests erupting throughout that period adopted radical tactics of taking over public spaces and impeding business as usual. The UNAM strike, however, was not just a brief confrontation in the streets. It lasted almost a year, during which students occupied the campus and shut down the operation of one of the world’s largest universities.

The strike was organized to defend the historic principle of free tuition at Mexico’s premier institution of higher education – with 270,000 students one of the largest and most respected in Latin America. Their key demand was repeal of a newly-instituted tuition in an institution that had always been free. The International Monetary Fund was demanding economic reforms, including ending government subsidies for public services. The government claimed it intended to charge only a symbolic amount – 800 pesos a semester ($85).

But students and university unions feared layoffs and other cost-cutting measures. Even 800 pesos was hardly a symbolic amount for many in Mexico. According to Alejandro Alvarez Bejar, dean of UNAM’s economics faculty, the average 5-member family at the time had an income of 5-6000 pesos (then $625-$750) a month, based on three of the five family members working full time. Millions of families earned less.

Students also charged that tuition and other reforms were part of a larger project to begin privatizing education. And in fact, over the next two decades Mexico’s national government did try to impose corporate education reforms modeled after those in the U.S., much as the students predicted.

In the twenty years following the strike, a virtual war was fought by teachers against the national government, not just over tuition, but to reverse the neoliberal direction of Mexico’s education policies. These battles culminated in the shooting of nine people at Nochixtlan, Oaxaca during a teachers’ strike, and the disappearance of 43 students at the teacher training school in Ayotzinapa, Guerrero. Finally, the conflicts helped fuel the election of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, eighteen years after the UNAM uprising.

On taking office Lopez Obrador echoed the criticisms and demands of that seminal student strike. “Neoliberal economic policy has been a disaster, a calamity for the public life of the country,” he told the Mexican Congress. “We will put aside the neoliberal hypocrisy. Those born poor will not be condemned to die poor.” And speaking to tens of thousands of people afterwards in Mexico City’s zocalo, he promised that “the so-called educational reform will be canceled, and the right to free education will be established [as mandated by] Article 3 of the Constitution at all levels of schooling.”

The UNAM strike of 2000, therefore, was a class battle, but also one played out in the arena of electoral politics. In the year of the strike, Mexico’s national government was still controlled by its old ruling party, the Party of the Institutionalized Revolution (PRI). The PRI sought to use the uproar over the conflict to prevent a rising leftwing political tide from winning that year’s presidential election.

In two previous national elections the leftwing Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) almost succeeded in taking power. In 1988 only massive fraud prevented its candidate, Cuauhtemoc Cardenas, from becoming president. In 1994, the ruling PRI campaigned successfully to elect Ernesto Zedillo by identifying Cardenas, who was again the PRD candidate, with the armed Zapatista rising in Chiapas. A vote for the PRI was portrayed as a vote for social stability, against armed conflict and social unrest.

In 2000 the PRI nominated Francisco Labastida, and Cardenas was the PRD presidential candidate for a third time. Labastida called for arresting the students as a response to what he called growing social chaos, much as Zedillo had used the suppression of the Zapatistas. In 1998, however, the mayor of Mexico City, one of the world’s largest urban centers, became an elected position for the first time. The PRD’s Cardenas was voted into this crucial office. After a year he resigned, however, in order to run for president once again. Rosario Robles, a PRD leader, then became mayor – the most powerful woman elected to office in Mexico.

By then the strike had started, and the students had broad public support, especially from the union for the university’s workers (STUNAM – Sindicato de Trabajadores de UNAM). Nevertheless, Mexico’s national PRI government never tried to negotiate with either students or teachers. Instead, it tried to order Robles to use the city police to occupy the campus and arrest students. She refused, saying it would violate the Mexican constitution. Cooperation would also have been viewed by PRD members as a political betrayal.

Instead, after the strike had gone on for nine months, the PRI itself intervened to occupy the campus, using its new anti-drug strike force, as well as army troops in police uniforms. Armed Federal agents arrested and jailed the leaders of the General Strike Committee (CGM – Consejo General de la Huelga), which students had created to organize demonstrations and the occupation of the campus.

After the arrests, Labastida criticized Robles, but in Mexico City the massive repression backfired. People were shocked when the military and police stormed onto the campus, a reminder of the violent and bloody massacre of students in 1968. Mexico, like most Latin American countries, has a tradition of university autonomy, which prohibits presence of government armed forces on the grounds of UNAM. In response over a hundred thousand people marched through the city to protest on February 9, 2000, an event documented in these photographs. During the march, large labor union contingents were interspersed among the students, in an effort to make difficult the arrest of those the government still sought.

The move by the PRI to end the strike killed its chances of winning Mexico City for Labastida. The most popular chant in the huge march was “Not one vote for the PRI!” But the Mexican countryside outside of Mexico City is more conservative, and the government’s message wasn’t intended for chilangos (Mexico City residents) anyway. In small towns and villages, the message of maintaining social stability was intended to keep the continued loyalty of a small, wealthy elite and the votes they controlled.

In the end, Labastida lost, but not to the PRD. People disgusted with the PRI’s long corrupt reign, but manipulated by its social chaos propaganda, voted instead for Vicente Fox, candidate of the rightwing National Action Party. Students and their supporters paid the price. The charges against them were extreme. While the government admitted there was only minor damage to classrooms, 85 student leaders were charged with terrorism and denied bail. Arrest warrants were issued for another 400.

Nevertheless, the PRD’s own relations with student leaders were often very difficult, although many strike participants were sons and daughters of the leftwing party’s members. But the arrests united a very divided opposition. “While there were many disagreements on strike strategy, the government’s action brought everyone together,” said Jesus Martin del Campo, vice-chair of the PRD delegation in the Chamber of Deputies, and a founder of the radical caucus in the national teachers’ union. “We all agreed that arresting the students and occupying the campus was wrong.”

While the arrests and the police invasion of the campus were the immediate issues that brought together city residents, the underlying reason for the outpouring of support was economic. UNAM had been the place where Mexico’s elite educated its children – the one place in Mexican society where they mixed with children of the working class. That mixing was a product of the free tuition and open access, guaranteed in the Mexican constitution in the wake of the revolution at the start of the twentieth century. Beginning in the 1980s, however, the wealthy increasingly began sending their children to private universities, which grew rapidly. They often went on to postgraduate work in the U.S., a choice unavailable to those without the money to pay for it.

The situation for most UNAM students was far different, however. Explained Alvarez Bejar, head of the economy faculty at UNAM, “Young people, when they get married, still live with their parents since they can’t earn enough to live independently. This was a key argument during the UNAM strike, and the reason why it had so much support.” PRD Senator Rosalbina Garabito, an economist, called the tuition proposal part of a larger picture. “The Mexican government has been enforcing an economic policy using high unemployment and falling wages to attract foreign investment,” she said at the time. “Mexican workers have lost 70% of their buying power since 1982. For every 10 new jobs created, 6.7 have salaries below the level workers actually need to survive. We need to democratize the country, not just change political parties.”

It took another 18 years and three elections for the left to win Mexico’s national contest. And when in 2018 Lopez Obrador, himself a former Mexico City mayor, was elected president, it was still far from clear that he could implement his promised change in direction. The student strike of 2000, however, had shown long before that militant direct action could mobilize broad political support for education as a basic human right.

…