Tijuana truly is a sanctuary city

By Myrna Santiago

This is the fourth and last in our current series “Reflections on The Border”

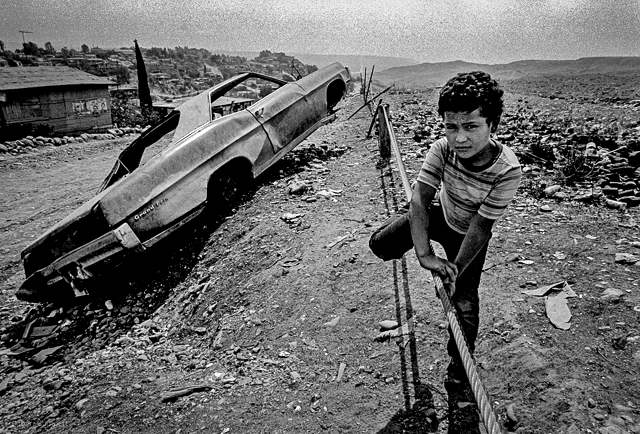

Tijuana was the hometown of my childhood. I was born in the US, but I lived across the border in Tijuana until I was 12 years old. My memories of the city, therefore, are those of a girl: sleeping late because I went to elementary school in the afternoon session, playing with my younger brother and our friends in a dusty yard where not even weeds grew, visiting my aunt and cousins about ten blocks down the neighborhood, enjoying the special aroma of moist earth after the rare first winter rain, feeling sorry for the poor children who lived in cardboard hovels in the dry river channel. We rarely crossed over al otro lado, to the other side, the United States, because immigration officials had refused me entry once, thinking that I was not really a US citizen because I spoke no English even though my mother showed them my US birth certificate. They suspected my mother was smuggling me with a borrowed document and thus they protected the homeland from me and sent me back to where I came from, Tijuana. When I finished sixth grade, my mother decided it was time to migrate for good. As a single mom, she could not afford secondary school for me, so we moved to Los Angeles. After that, visits to Tijuana lasted one day: leaving LA early in the morning, spending the day with my cousins, shopping at one of the supermarkets for our favorite chocolate, cookies, pan dulce, and mole, and returning to East Los late at night when the line to cross did not take hours. I carried that blue US passport and my English was pretty good, so la migra could not keep me outside the country anymore.

Fast forward some twenty-five years later. I return to Tijuana as a professor of history, focused on would-be migrants subject to US immigration policies going from bad to worse, from Obama as the “Deporter-In-Chief” to “Trump the Cruel” who tears families seeking refuge apart and puts the children in cages. And Tijuana is one of the stages where much of this suffering and drama is taking place. Haitians walked to Tijuana from Brazil when their visas to build sports venues ran out in 2016 and they could not return to an island so ravaged by colonialism, earthquakes, hurricanes, and US support for coups and dictators that they ended up in my childhood hometown. Tijuana is home to some 3,000 Haitians now, adding to its diversity, working in restaurants, selling cold agua fresca to motorists waiting for hours to cross the border. The first time I went to Tijuana with a colleague from Saint Mary’s in February 2017 there were signs in restaurant windows along the strip, Avenida Revolución, reading: “Haitians welcome here. Jobs available. Inquire within.” If migrant shelters existed when I was a child, I never knew about them. But now there were two literally around the corner from my elementary school. In 2017 they housed men from southern Mexico heading north and an increasing number of deported Mexicans from California, Oregon, and Washington, not knowing where they were heading, not knowing when they would see the families left behind in the US, not knowing what Mexico meant for them after ten or fifteen years living and working in the US.

But especially bewildered were young men who were my opposite: they were Mexican citizens by birth, but they had grown up in southern California. They spoke no Spanish, but lacking the proper documentation to live in the US, ICE captured them and tossed them over the wall to Tijuana. At my neighborhood shelter there were few people for them to talk to, to pass their wisdom about life in the US, since they shared no language in common. From other deported American Mexicans they heard they had a good shot at getting jobs in Tijuana because they spoke English. The call centers, the American maquiladoras (assembly plants), and the “hospitality industry” all wanted English-speaking employees. The growing foodie scene in Tijuana was eager to test out the restaurant skills deported men brought with them as well. Making some money gave young men hope of finding an attorney who might know enough about immigration law to help them return to their parents, friends, and girlfriends in LA or Orange County. In the meantime, Tijuana welcomed them.

“ICE delivered them to Tijuana–the irony that Tijuana used to be a pleasure center for US servicemen clearly lost in translation.”

Tijuana, too, hosted veterans of the US armed forces who were being deported right and left. They had never had the proper paperwork to live in the US, but the armed forces were happy to take their lives and bodies and deploy them to Iraq, Afghanistan, the war du jour. The service promised them citizenship but never delivered. Instead, ICE ushered them into armored vans if upon their return to civilian life they found the adjustment difficult, slipped, and ended up serving time. When their sentences were done, ICE delivered them to Tijuana–the irony that Tijuana used to be a pleasure center for US servicemen clearly lost in translation. The veterans’ cave in a northern colonia was a slice of Americana: an extra large US flag pinned to the wall, medals and insignia scattered throughout, camo bunk beds, a tight schedule posted on a whiteboard for those staying at “the bunker,” with exercise, prayer or meditation, work, dinner, lights out. Their most pressing demand: access to the VA in San Diego for health care, particularly mental health services. The men were grateful for Tijuana, who honored them with murals painted on the wall that divides both countries and part of the Pacific Ocean at Playas de Tijuana, but they expected the country which they served to take care of them. After all, they had put their lives on the line for the US. Since last fall, 2018, Tijuana has witnessed the arrival of an exodus of biblical proportions from El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. These are no longer men alone seeking opportunities to send remittances home, but entire families fleeing from unimaginable violence. Tijuana has its share of narco-violence, but it has not become the daily bread for an entire population. Gangs, narcos, paramilitary groups, police, private armies protecting monocrop plantations or cattle ranches—you name it, the Central American countries have all the above in spades. And none of those groups hesitate to kidnap, torture, rape, disappear, and execute men, women, children. So the people flee as far as they can go and Tijuana is the end of the line. There they meet a wall, 30 feet high, with barbed wire on top sometimes. Tijuana does its best to assist. Shelters bring out more cots. Neighbors contribute more diapers. Solidarity groups from San Diego send more clothes. The religious community in Tijuana responds lovingly, asking the citizenry to not give in to donor fatigue, to listen to their hearts, to open up their wallets and donate groceries one more time. They find teachers for the children to learn their ABCs while they await word from the mighty ICE on high. But they are deeply concerned. Local politicians blame the victims, traffickers lurk in wait to exploit the refugees, and corrupt officials try to make a buck off the suffering of the Central Americans. The shelters are terribly overcrowded. A volunteer at a women’s shelter asks, “if the US government carries out the massive deportations it is threatening to do and sends thousands upon thousands of people to Tijuana, where will they stay?” The city is not prepared for them. For now, however, that dusty patch of desert at the farthest northwest corner of Mexico, Tijuana, does not turn away those seeking a manger to lay their babies to rest. My childhood town has indeed grown up in ways it never imagined. Tijuana truly is a sanctuary city. Its people are generous toward the refugees despite their own poverty. That is a story that is yet to be told, a story that merits not only attention but emulation. That all other cities, on both sides of the border, would follow Tijuana’s example.

.