Beyond the Waterfront!

By Peter Olney

Editor’s Note: Just as I was sitting down to read Peter Cole’s excellent book, a dispute broke out in the Port of Los Angeles over automation and the future of work.I couldn’t avoid commenting on that dispute and much of my review examines the challenges facing the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). But as an activist historian I am sure that Peter will not mind the fact that his work inspired me to think about the future of workers on the waterfront and beyond. Solidarity!

.

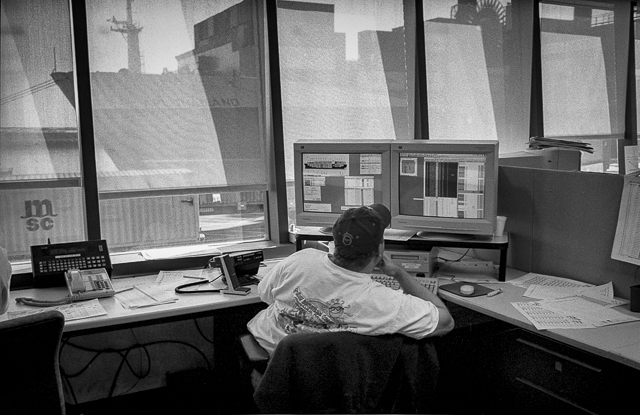

Photo: ©1983 Robert Gumpert

Book Review: Dockworker Power Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area, Peter Cole, University of Illinois Press 2018

Almost alone among unions, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) employs a full time librarian and archivist. In my 17 years as Organizing Director I would often take my lunch down to the third floor of the union’s headquarters in San Francisco and gab with Librarian Gene Vrana or his successor Robin Walker. Beyond maintaining the union’s archives, books, newspapers, clippings and oral histories, they were both a treasure trove of knowledge about the union’s history and traditions. Perhaps no other union in the United States besides the United Auto Workers has been the object of so many histories, articles and speculation. Peter Cole has added a fine volume to that pantheon with his comparative study of dockworkers in the Bay Area with their counterparts in the Port of Durban, South Africa. His book recently won the Philip Taft Labor History Book Award for 2019.

Cole’s Contributions

Cole focuses his examination of the two dockworker groups on their often unheralded contributions to the struggle for racial justice. He also examines their responses to port automation – the introduction of containers. And finally he draws out their participation in international solidarity actions.

In two very interesting observations Cole contextualizes working class power in time, place and socio-political conditions.

First he draws out a discussion of the process of casualization and how it can serve or inhibit the working class struggle depending on social and political context. As many American readers know the “shape up” was the classic casual labor relationship on the waterfront prior to the great maritime strike of 1934 on the West Coast. The ship’s boss would come down to the docks looking for labor and pick a crew arbitrarily from workers “shaping up” on the waterfront. This was a system prone to extreme favoritism and discrimination based on caprice or the boss man’s strategic discrimination against troublemaking labor activists. The 1934 strike and its subsequent settlement put in place a hiring hall that was controlled by the union with a non discriminatory dispatch system. The hiring hall ”low man out” was a powerful weapon that eliminated the day-to-day power of the employer over the workforce and spawned much of the independence and political activism of the ILWU.

In South Africa on the other hand the “togt”, a labor system based on the causal labor of Zulu tribesmen who worked day to day with no permanent relationship to the employers, ended up benefitting the workforce in its struggle over wages and conditions. Unions were banned, and there was no permanent employment system so Zulus would just not “shape up” in effect striking but with impunity because they had no permanent employment relationship that they were severing. The employers later instituted an employment system in order to dominate and control labor.

A second example of the two unions and their comparative histories yields another historical irony and a deeper analytical point. The ILWU throughout the long struggle to end South African apartheid had played an active role in support of liberation. Nelson Mandela saluted the ILWU on his 1990 visit to the US after being freed from 27 years in prison. At a rally before 60,000- in the Oakland Coliseum he declared, “We salute members of the ILWU Local 10 who refused to unload a South African cargo ship in 1984….” Fast-forward to 2008 post apartheid and the South African Transport and Allied Workers Union (SATAWU) refused to unload arms from a Chinese ship docking in Durban. The arms were destined for the repressive regime of Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe. As Cole points out the South African constitution legally protected the SATAWU action in 2008, and a South African judge ruled in favor of a potential freight boycott, whereas in 1984 a San Francisco Federal judge slapped the ILWU and boycott leaders with injunctions.

This difference spotlights a more profound point, one very artfully articulated by sociologist and researcher Katy Fox-Hodess, “These economic and material dimensions of worker power only tell part of the story. A narrow focus on these dimensions without consideration of the broader social and historical forces shaping the terrain of struggle in the industry leads to an overestimation of possibilities and the underestimation of challenges”. (Presentation at Historical Materialism Conference, London November 2018) Fox-Hodess, who worked for the ILWU as an organizer before beginning her academic career, forces us to remember that social and political context can lead to very different results in the class struggle. I have often made this point by suggesting that while dockworkers in Singapore may have a very similar structural power at a choke point node in the economy to their counterparts in Durban in 2008 or Oakland in 1984 for that matter, their ability to act is limited by a military dictatorship and the possibility of extreme physical repression.

At 221 pages Cole’s book is a very worthwhile read. It taps a lot of exciting scholarship and oral histories to make some important observations in addition to those mentioned above. Six chapters unfold his story of the fight for racial justice in both ports, the struggles around automation and international solidarity actions. The book relies heavily on secondary and tertiary sources because most of the original combatants are deceased. As with many treatments of the ILWU it tends to highlight, but not uncritically, the glorious history. In fairness to Cole he does not pretend to make prognostications or give strategic guidance for the future, although such guidance is latent in the history of the union. That is why I found very telling the quote from Clash front man Joe Strummer that Cole uses in the opening of his concluding chapter: “The Future is Unwritten” This is the title of an album that Strummer and his band did, and the title of a movie about Strummer made in 2007 three years after his death. How does the union’s history help us to write that new history? This new history would be a new course of action that can overcome the union’s increasing isolation on the docks and the existential challenge of automation.

History as a Guide to Action

The early leaders of the ILWU recognized that their docker power was not an island. Seeing that their work was interconnected with warehousing that often took place right across the Embarcadero they conducted the famed “March Inland” of 1934-38 that is well documented in Harvey Schwartz’s book The March Inland: Origins of the ILWU Warehouse Division which is mentioned in Cole’s volume. This “March Inland” resulted in the union covering its strategic flanks along the supply chain, and it resulted in creating a warehouse Local 6 whose numbers rose to 20,000 in the early 50’s far outnumbering Local 10 and the longshore division. This local and its numerical superiority meant that the International Secretary Treasurer of the Union until very recently was elected out of the Warehouse ranks. It also rooted the ILWU in the broader working class preventing if from being an isolated aristocracy of “Lords of the Docks”. The numbers in the Warehouse Local alone created a presence in the community that meant that Longshore Local 10 was not isolated socially and politically from the broader community but swam in the working class sea. This was also true in the Puget Sound and Los Angeles where Locals 9 and 26 provided an anchor into the broader working class. Interesting to note that the first Latino President of Local 26 was Bert Corona the legendary Chicano leader and founder of Hermandad Mexicana.

No one grasped this lesson more profoundly than Lou Goldblatt, the longtime Secretary Treasurer of the International union who came out of the “March Inland” in the Bay Area. When he was sent to Hawaii to help the organizing effort of the longshoremen there, he observed, “One of the conclusions I reached was that longshoring played a different role in Hawaii than it did on the mainland. Instead of being a general industry of longshoring, in Hawaii longshoring was just a branch of the Big Five (Sugar and pineapple giants like C&H, Dole, Del Monte)”” The docks could not be held without controlling the chain, the flanks. This led to the ILWU’s organization of the thousands of sugar and pineapple workers. When the sugar and pineapple plantations were phased out the new resort hotels were organized by the ILWU using the power of its numbers and its political reach so that the ILWU to this day remains the largest private sector union in Hawaii and a statewide political power. This is political power that sustains whatever actions the 900 long shore workers may take on the docks. Having a union with 25,000 members on the Hawaiian Islands with a total population of one million people means a density that permeates community and politics and makes everything easier especially the new organizing of workers. All the solidarity actions and support for racial justice are grounded in a reality of a broader community that both benefits from docker power but bolsters it and strengthens it.

Employment Trends Away from the Docks

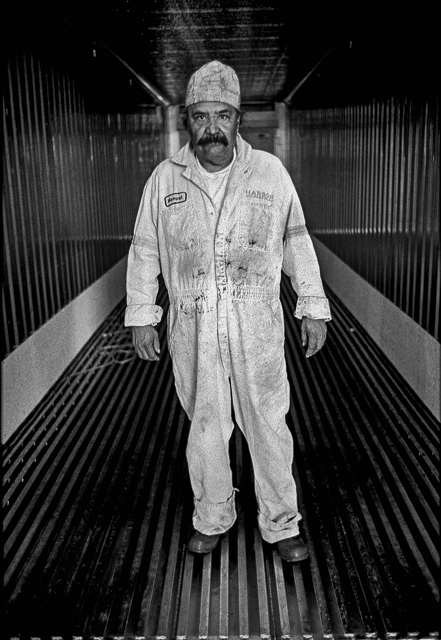

Photo: ©2000 Robert Gumpert

In the glory years of the “March Inland” in the Bay Area the targets were very apparent, often across the Embarcadero in a coffee warehouse or manufacturer or other storage facility or processing plant with geographic proximity to the docks. While the proximity may not be the same the relationship between docker work and inland employment is easily understood. The ILWU is well aware of the studies that have been done by industry observers and academics on the growth of maritime logistics employment away from the waterfront. Nobody has better documented these employment trends than Professor Peter V. Hall at Simon Fraser University. (page 251-252 Choke Points, Pluto Press 2018) He details the massive growth in container traffic through the West Coast ports. In 1980, 2.1 million TEUs were handled in the ports of the West Coast. In 2010, 14.9 million units were handled. This is a 620 percent increase. In this same period of dramatic cargo growth the growth in long shore, or on dock employment, has grown but at nowhere near the rate of cargo trends. It is important to remember that in 1960, prior to the advent of containerization, there were 26,000 longshore workers on the West Coast docks. In 1980 after the establishment of containerization as the dominant mode of cargo movement, there were only 10,245 workers left on the docks. In the period that Hall details from 1980 to 2010, employment grew to only 13,829, a rise of only 35 percent, and puny when compared with the 620 percent increase in production. There is no mystery to this disparity. Containers and massive capital equipment have replaced longshore gangs in the United States and around the world. Before containerization a ship would call for two weeks to be loaded and unloaded. Today the process can take less than 24 hours. While these increases in employment keep pace with regular employment trends, the real job growth action is off dock on the West Coast in three areas:

Photo: ©2000 Robert Gumpert

- Logistics information services: from 1980: 12,816 to 2010: 47,890. This is 274 percent growth. These are information service workers who track the flow of cargo and equipment worldwide. Often they work at inland office centers far from the docks. For example Evergreen, the giant Taiwanese carrier, has a massive information center in Dallas, Texas, far from any port, and purposefully so.

- Warehousing: from 1980: 12,738 to 2010: 86,737. This is 581 percent growth. These are inland warehouses and 3 Party Logistics centers that provide warehouse and order fulfillment services to giant retailers that are clients of the giant carriers that employ dockworkers in the ports.

- Trucking: 1980: 156,808 to 2010: 257,673. This is 64 percent growth. The increases in these off-dock sectors are much more in keeping with the triple-digit increases in cargo volumes. These drivers are often called “owner operators” or “independent contractors,” and therefore their wages and conditions are eroded because they are treated as pieceworkers and paid by the load, especially in short-haul trucking. Many of them, particularly doing short-haul trucking, were once members of the Teamsters. After deregulation on 1981 the Teamsters lost control of this short-haul cargo “drayage” sector.

These growth sectors are the inland flanks of the ILWU, and in order to preserve its power and viability the union must organize these workers and/or assist other unions in doing so. The surprisingly close relationship between Bridges and Teamster leader Jimmy Hoffa was based on a mutual understanding of the linkages between maritime freight and trucking.

Fighting Automation or Growing Union Power?

In Chapter 4 Peter Cole deals with the question of automation. This chapter rehashes the debates around the historic M&M agreement of 1960, and whether it was the right move or not by Bridges. The 1971 strike is studied again as rank and file reaction to the M&M and containerization and steady man provisions that weakened the hiring hall. Bridges is again second guessed for his consideration of a merger with the IBT, although it could be argued that he correctly saw that the ILWU long term could not exist as an island isolated from other workers in the supply chain – like truckers and warehouse workers.

Photo: ©2000 Robert Gumpert

There is only one scant mention by Cole of the Container Freight Station (CFS) supplement of 1969 that was the union’s belated attempt to deal with the issue that haunts the ILWU to this day. The CFS agreement provided that longshoremen would stuff and unstuff the freight from containers, meaning that the work that was formerly being done in the hull of a ship would be done in loading and unloading a container filled with goods for multiple consignees. This work was required to be done union or the employers would be fined $10,000 per container. The language of the CFS agreement provided for a 50-mile radius from the port within which the CFS language would be in effect. This was the Union’s half hearted and ineffectual way of capturing the “functions” that used to be part of loading a traditional cargo ship. The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and the Courts have clearly held that this provision is unenforceable, but this continues to be the Union’s feeble and unsuccessful response to a vast increase in inland employment in the supply chain. Nowadays there are not multiple consignees to a container. In the case of Wal-Mart or Amazon they import thousand of containers annually and unload them in third party warehouses or their own distribution centers. This is where there has been massive growth in employment so while the union can bash on dock automation the Employers are running for touchdowns inland.

I played defensive tackle in high school. I was big and strong and loved physical contact. When an opposing player came out to block me I loved to pound the blocker into the turf with sharp blows from my forearms. I was often effective in doing that, but I’ll never forget my defensive line coach rolling an embarrassing bit of game film forward and backwards showing me devastating my immediate opponent but also showing the offensive ball carrier running right by me for a big gain. The coach would say, “Nice job on the blocker Pete, but the point is to tackle the ball carrier.”

This is a good metaphor for the struggle going on now on the West Coast with respect to the marine supply chain. Let’s keep our eye on the ball carrier and the future of the supply chain. It has been amply demonstrated that growth in employment in the marine supply chain for a long time has been away from employment on the docks.

Photo: ©2015 Robert Gumpert

Automation in the Port of Los Angeles

Recently the ILWU has been engaged in a massive battle in the Port of Los Angeles with Maersk over the automation of Pier 400, which will cost the ILWU dozens of jobs and lots of work hours. Powerful mobilizations of the San Pedro/Wilmington community and the workforce have taken place attempting to stop through the political process the introduction of those robots, which were agreed to by the ILWU in a 2008 Memorandum of Understanding with the Pacific Maritime Association, the employers group. The settlement of this battle has resulted in the ILWU getting a commitment from Maersk to fund training for ILWU members to do robot maintenance and repair, pretty much what the union negotiated in 2008. The merits of this settlement can be debated, but two things are clear: The robots are coming, and Maersk has its eye on the ball and its corporate future and is engaged in its own “March Inland”. In a fascinating recent article in the Wall Street Journal Maersk reveals its plans to achieve a company makeover from 80% of their earnings coming from container shipping to “Hopefully a couple of years from now will be much closer to a 50-50 scenario between ocean and non ocean services” Chief Executive Soren Skou says. Maersk already runs 20 warehousing and distribution centers in California, New Jersey, Texas and Georgia. Five of them operate in the Southern California basin.

Maersk realizes that to meet the needs of Wal-Mart and Amazon they need to focus on a streamlined factory-to-store door or warehouse door service. Amazon is already in the Non Vessel Operating Common Carrier (NVOCC) business whereby they buy space on ships for their own use, but also sell unused space to other customers. They could soon contemplate buying and operating their own ocean carriers. Maersk is not alone in this strategic approach. Other major carriers like the French company CMA CGM are engaged in the same strategy extending their employment reach inland. CMA CGM acquired CEVA Logistics in April.

Imagine if the resolution of the dustup in the Port of Los Angeles had been Maersk granting organizing rights to the ILWU in all its subsidiary warehouses and information service centers? This would result in hundreds if not thousands of new members and jobs, and it would solidly root the union beyond the waterfront and in the broader community. Most of these warehouse workers are low wage non-benefited immigrant workers. The rising demographic tide of Southern California would be embraced by the “Lords on the Docks” breaking their political and community isolation from the broader working class of the Southern California basin and establishing a long-term future for the union.

Peter Cole has done us a great service in his comparative history. He has demonstrated that the social and political context of unions is important in determining their course of struggle, and he has highlighted the great impact that dockers have had on social justice struggles.

The future can be written, not by doting on the docks but instead by embracing the ILWU’s history of the “March Inland”. The union must conceptualize itself as a logistics union and move beyond the waterfront to make new history! The survival of the union and its power depend on such a strategy, and the union’s history teaches that.

…

Building upon the previous comment, or, using a phrase from Lao Tzu, about the utility of a home. Build a house with windows and doors, the utility is where there is nothing. That’s the House of Labor, too, what Montgomery wrote about. I gave Peter Olney a house to consider, when he first came to ILWU, from the top. It was about my research and activism in the ILWU Inland Boat Union. We had spliced OCAW program — led by Tony Mazzocchi and Steve Wodka — into our own campaign to organize oil cargo longshore work.

https://www.tandfonline.com/eprint/QWKjiwC62kXhKgmtuGTD/full

He talks about solidarity. But he doesn’t practice it. In academia it would be called plagiarism.

Peter Olney’s review of what is clearly an important book by Peter Cole speaks directly to what should be a central question for all unionists. Perhaps the most important challenge facing the labor movement is how to leverage strength in existing areas of union concentration in order to more build working-class power beyond its current limits; to organize the unorganized through the struggles of the already organized. Too often, however, union leaders and activists are trapped within the limits of one company or one sector. In the heat of the moment this is an understandable orientation, yet it is one which plays to management strength. In a global economy defined by financialization and by rapid implementation of new technologies, that will always leave labor in a defensive position vis-à-vis management.

The need for strategic links that coordinate union initiatives throughout the industrial process was a need we recognized in the International Union of Food and Allied Workers already in the 1980s. After all, another way to look at “farm-to table” is through the coordinated labor of farm workers with transport and industrial production workers all the way to workers at restaurants and grocery stores. Yet we were unable to forge such linkages in a meaningful way; that will only be possible when initiated by local and national unions building organic ties to their “near beyond” in their organizing and bargaining and thereby creating a framework to confront capital as a whole (and not incidentally build genuine solidarity across lines of division through shared work and relationships). The ILWU – with its strengths and its limitations – is one of the few unions in North America to have addressed this in a serious and on-going way as Olney discusses in his review. In particular the success of the “March Inland,” in the post-World War II days on one side and the failure of dealing fully with the consequences of containerization are meaningful to redefining possibilities in the moment. It is a set of experiences that should be looked at, learned from and built upon.