Jeff Adachi, Public Defender

By Pete Brook

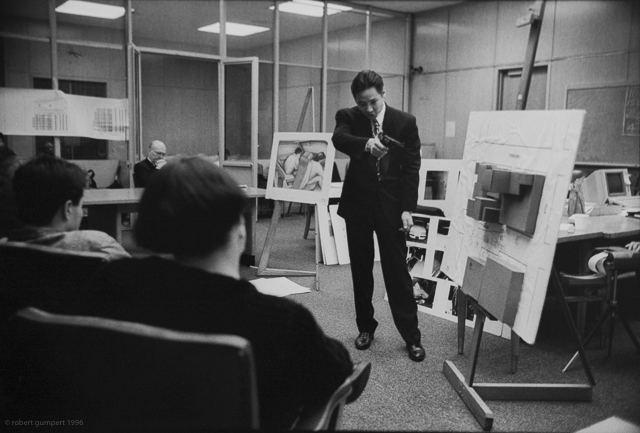

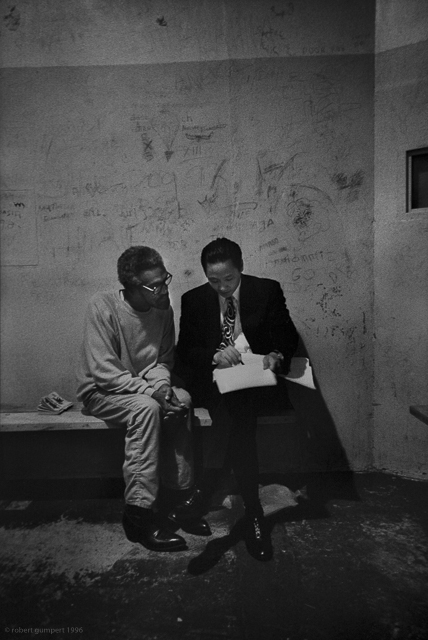

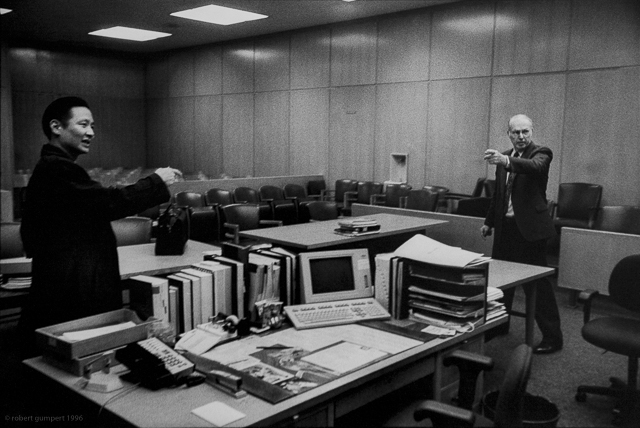

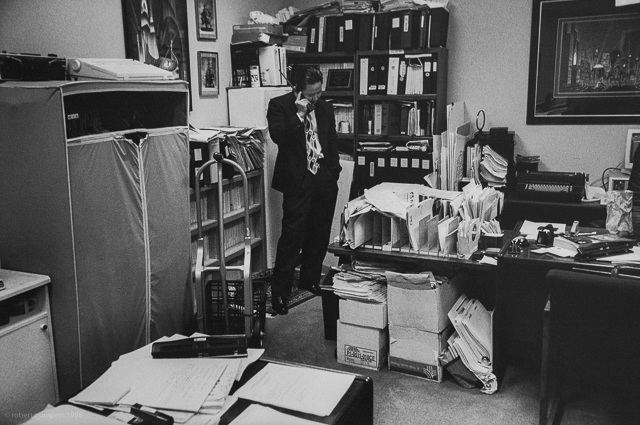

An editor’s note: Both Jeff Adachi and Pete Brook are my friends, people I know through my photo work in the criminal justice system. Pete Brook has been concerned with the use and power of images in conjunction with the criminal justice system for many years. I meet Jeff sometime in 1995 when he was a deputy public defender working a murder case. I spent 18 months and we remained friends.

Jeff Adachi was a public servant for over 30 years. From 2002 until his unexpected death on February 22nd, 2019, Adachi served as the head of the San Francisco Public Defenders Office. San Francisco is the only county in California that has an elected Public Defender. Adachi won re-election five times. Such was his suitability, leadership, fierce advocacy and approval in the role, he ran unopposed four times.

In 2015, in association with the photography exhibition Status Update about the changing San Francisco Bay Area, Adachi spoke with curator Pete Brook about images, society and justice. This is a full transcript of the interview published for the first time.

How do images play into the work of the public defender’s office?

The work of defense attorneys is very visual in the sense that we tell stories through images, through pictures. Often those pictures are conjured in the minds of jurors or judges, but more often than not, we use photographs to tell the story of our clients and what happened.

The Black Lives Matter movement and this discussion of race and criminal law that we’re having across the country would not be possible without images. The videos taken of Eric Garner and Tamir Rice are indelibly seared into the brains of millions of Americans. [Videos] caused Americans to take action and it changed their perspective.

Is the practice of law easier or harder in an era of total image saturation?

Clarence Darrow would hold court for nine hours in closing argument. Reporters would sit there and hang on his every word, reported verbatim in the newspapers. At trials in the 1930s and 40s! Daily coverage. You don’t see that anymore. Print media doesn’t have the resources for that type of coverage — we have very truncated versions. As a result, the media that comes out about criminal cases is very biased. You only hear about a person who’s arrested and when they’re convicted. We’ve tried to change that.

The Public Defenders Office is active in using media to tell clients’ stories. When they are acquitted, we put out a press release. It’s rare for public defenders to do that. If we have a photograph that captures the essence of a client who’s been wrongfully convicted, or of an officer breaking the law, we’ll use it.

Your office released a video of a public defender being arrested for advising her client in the halls of a courthouse?

Yes, two of my deputies filmed it, so we released the video on YouTube together along with some stills. We had a million-and-a-half hits within a week. The next day we had 1,700 emails of support that came in for her.

What sort of images do you use in court?

The courtroom it’s a very sanitized environment. You have jurors who may or may not be familiar with your client’s neighborhood or lifestyle. So photographs allow us to give the jury a mental picture. Also, if you’re trying to describe the scene of the incident or crime, or if you’re trying to show the importance of DNA evidence, or if you’re showing an eye witness identification, pictures are critical.

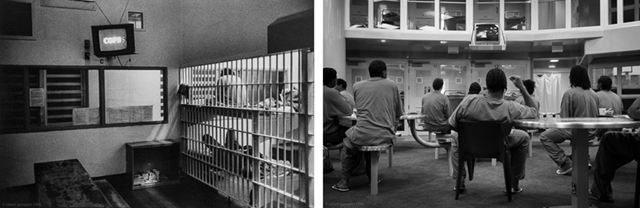

There are very emotionally-charged pictures. When you see a picture of somebody who’s dead or someone who was seriously injured, it has an impact on you. Similarly, when you see a picture of a person in jail, a person locked up, a person deprived of their dignity, that’s impactful.

Justice Kennedy used three photographs in the appendix to his majority ruling in when the Supreme Court heard Brown v Coleman/Plata. That caused a lot of consternation because some legal boffins don’t think photographs have a place in any Supreme Court ruling. There also an accusation that photography is emotive and not rigorous or reliable enough.

Anytime you’re stimulating visual senses, you’re going to be accused of manipulation, but the only way that we can completely perceive something is to be able to see it. And even though they justice is blind, jurors and judges are not.

How often have you argued with the prosecution about the inclusion of an image in case proceedings?

One of the things that we often show are photographs of our clients and families. We get an objection to that because the prosecution doesn’t want the jury to see that our clients have a family.

And what do you which to exclude as defense attorneys?

We will typically move to exclude photographs that we find, or believe, are prejudicial — grizzly photos or ones that show a grizzly injury, photos that would inflame the jury.

What are your thoughts on the economic gap between the rich and the poor?

The gap has grown more in favor of rich people. The number of San Franciscans living at the poverty level is at about 13% which is commensurate with other urban areas.

But better than the Bay Area as a whole, in which 20% live at or below the poverty line.

San Francisco is very much a tale of two cities where you have on one hand, very wealthy people who have been living here or who are moving here and can afford the high rents and the multi-million-dollar homes. And on the other hand, you have people that are very poor, living in housing projects, barely scraping by.

Does this inequality have a measurable effect in San Francisco and in the Public Defenders’ work?

Right now, there’s a huge debate about increased incidence of property theft in the city. What’s the reason for this? Is it because Proposition 47 reduced theft offenses from felonies to misdemeanors? What accounts for the increase in auto break-ins and cell phone theft?’ It’s need. And it’s an easy way for people to make money. It’s pretty much a supply and demand society. If you’re walking down the street carrying your cell phone on your open palm and somebody comes up and takes it from you is that really that much of a surprise? Well, you know, most people believe that society is safe and that they’re able to do whatever they can but, unfortunately, our country’s not that way.

Do you have any ideas, either a citizen or as a professional on how you deliver economic justice?

They’ve always said that it’s about jobs. Provide more jobs, then people aren’t going to be involved in crime. That’s partially true. We also have to work, particularly with young people, at changing value systems. If somebody becomes pre-programmed that selling drugs or stealing is the best way for them to survive, then they’re going to continue to do that. Even if you’re getting them a minimum wage paying job.

We have to get people to substitute in new values — hard work or cost-benefit analysis: “Should I do this or do that? If I get arrested, I could be in jail for six months and be out of operation. You know what, I’m going to choose this instead.” Getting people to make better choices based on evolving value systems is a much harder thing to do.

How do you think San Francisco is doing with its allocation of resources? Many compare education and incarceration budgets for example. How are we doing allotting our money and our energies?

Will we define happiness by how much money we have? What can I do with the money? What kind of clothes can I buy? What kind of car can I have? What kind of bicycle can I have? Particularly in an urban city like San Francisco where we’re obsessed with food, about status, about sex. We’re obsessed about entertainment. We have become, in many ways, disenfranchised with who we are as human beings. Many of us don’t relate to the struggles of everyday people

Often, the people who can be on juries are middle class or upper class, and not like our clients who have been convicted of crimes. How do you get them to understand what it’s like to struggle as a poor person in San Francisco? There are a lot of people who live in San Francisco who have nothing and they wind up sometimes in the criminal justice system. We wonder how they got there. Yet, it’s very predictable when you look at the lack of education, or the fact that many haven’t had opportunities to work, or that many live in a situation where racism and discrimination is an expected part of life. As public defenders, we help judges and jurors who have power over a client’s life to exercise that power in a way that’s going to help and support them as opposed to simply bringing them back into the system.

Do we know one another enough in the Bay Area?

We have a social justice programs at our office called the Magic Program. It’s a literacy program but we have a 2-month program where kids from the Western Addition are taken around San Francisco and exposed to different experiences. Some kids had never been to Japantown, the neighborhood next door, and didn’t know its history or the culture. We need to get children experiencing and learning new things. We have to spend more time on gaining cultural, racial and social equity — if we begin to look at our brothers’ or sisters’ problems or our neighbors’ problems as our own then we can collectively solve them.

Of course, in a city like San Francisco a lot of people are new arrivals. Many, as you’ve said, wealthy by comparison and can afford to move here. Solutions can come from the wallet as well as from being open with your neighbors, yes?

The idea that people should give back, in terms of giving hard dollars, to support various (things), whether it’s arts enterprise or something else that you want to see in your community, you just don’t see that as much. I’ve been involved with philanthropy for a long time, and I find that the people who are most giving are San Franciscans who have been here and that have that connection to the city. If I don’t have a connection to my school, I’m not going to help at the school reunion. We want to encourage people to take more of an active role in our communities. That doesn’t just mean volunteering or tutoring but, you know, really putting some dollars behind it.

Do jails work?

No.

Do the jails of San Francisco county work?

Incarceration generally doesn’t work.

If your objective is just to lock somebody up to keep them separated from society, then, sure, that works. Does it make them less violent? No. Because we’re locking them up with other people who may be even more violent. Does it teach them how to get a job when they get out? No. Does it help them evolve as people? No. There’s got to be a rehabilitation part of it. What they found as most effective in deterring bad behavior is when a person knows a penalty is coming and it is executed within a certain period of time and very quickly. So if I tell you, ‘If I see you in this neighborhood again, I’m going to give you two days in jail.’ It works.

A clearly stated and immediate response to an action?

Social science has taught us, yes. Now, does that mean that’s the best use of resources? It depends. If you’re going to lock somebody for using drugs, no, I don’t think so. If you’re going to lock somebody up for stealing a cell phone, maybe.

San Francisco has had some public profile cases of deputy misconduct in the jails and SFPD officer misconduct on the streets. Why?

We need better vetting of officers. Better use of the implicit bias testing to determine whether an officer suffers from bias and help them address that both when they’re hired and when they become police officers. By vetting I mean really looking at their record, talking to people. Just like you would if you worked for the FBI. That doesn’t occur now. You just need a high school diploma. I think officers should be required to publicly disclose when they’ve used force, excessive force and why.

Most cities have officer accountability boards. But what do they really do? In San Francisco, we have the Police Commission that oversees a lot of the day-to-day policy setting, but we’ve never had the police commissioner expose a scandal involving officer. And yet, we’ve had scandals left and right in San Francisco. We had officers who were breaking into people’s rooms and stealing things without warrants, and the Police Commissioner was silent.

As a public defender, our mission is to expose police misconduct. I’d like to see officers who have multiple complaints against them for certain types of misconduct to be terminated earlier. Accountability includes collecting better statistics. One of the things that we worked on was some legislation that requires a police department to report not only the gender and race of people they arrest but also the reason why they stopped them.

And what about law enforcement officers under investigation?

Law enforcement officers are held to a different standard. If you ever see a cop who’s brought into court for some charge, they’re released the same day. They often don’t even have to surrender. How does that happen? Are they part of a royal class? No. They’re treated differently. Why is that a police officer gets in trouble — boom — he’s able to meet bail? How is that law enforcement officers usually get their charges dismissed? I’m not saying that in every case there’s a determination based on money, but I’m just saying that that plays into it. Wealth, privilege, and race effect how people are treated in the system.

The SF Public Defenders office is in favor of body cameras?

I think body cameras are going to be important part of reform. We’re a part of the community that’s determining that policy. We think they will reduce the complaints against police officers, and definitely reduce the use of excessive force and violence.

How do you assess the health, not only of San Francisco and the Bay Area region?

We have to do more to keep families in San Francisco, to address the lack of housing. It’s probably the biggest issue that people are facing here right now.

I don’t know that we need to grow as a city. They’re talking about having a million people living here by 2025. I don’t know what that’s going to look like. I see it changing and I think we have to look at conserving part of who we are. I’m not saying that we shouldn’t modernize with the times, but if we become the kind of city that only tolerates people at a certain income level and housing at a certain price, it’s not going to be a place that I want to live.

Finally, it’s important that we support the arts in San Francisco. Art is a big part of our humanity. It’s really tragic to see a lot of our arts organizations go. Art is the cultural health of the city. That’s one area I’m really worried about because I see a lot of groups either disappearing or moving.

…

Thanks for this, Jeff was a lifelong activist and good guy, we’ll miss him. I never met him, but communicated with him a few years ago when I was cataloging an Asian Pacific Student Union poster for the defense of Chol Soo Lee (which can be seen in the hyperlink associated with this post). Lee was a Korean immigrant wrongfully convicted of a 1973 murder. While in prison he was further sentenced to death for a murder in self defense. Persistent community activism and legal support resulted in his release in 1983. Note the stanza from “The Ballad of Chol Soo Lee” singers – yes, that’s Jeff.

http://collections.museumca.org/?q=collection-item/20105410581