Pictures that Speak

By Earl Dotter

In his film BlackkKlansman, Spike Lee paired effective dramatization of the KKK in Colorado in the mid-1970’s with traditional film photojournalism of the Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville in 2017. By doing this, Lee brought the currency of that recent live Charlottesville footage to inspire a film that speaks in the most immediate of ways about the long and ever-present history of racist hate in America. The film effectively employs photojournalism to point directly to the visceral bigotry that President Trump has enabled today within the U.S.

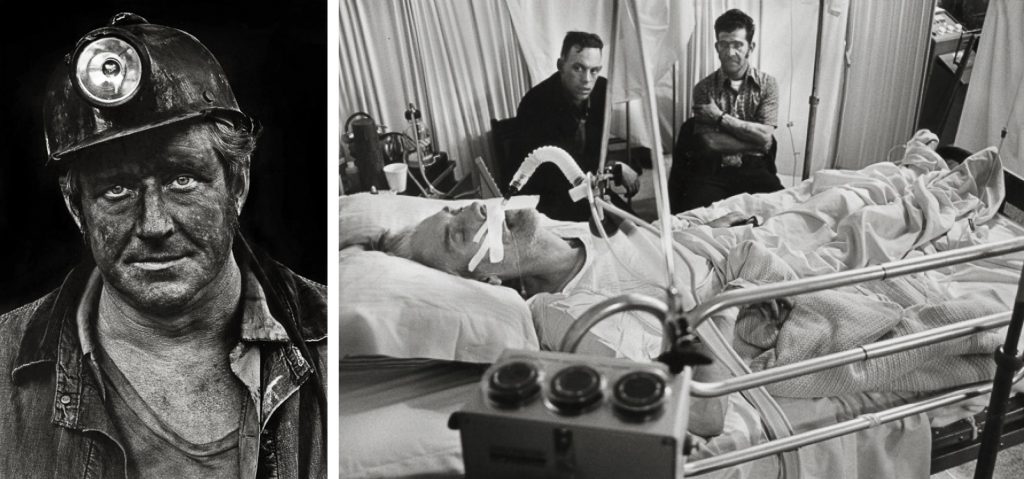

As a photojournalist of working people in the United States since 1968, I am aware that the lives of my subjects are often far harsher and more painful than those of my viewers. To bridge the gap, I look for common ground that workers I photograph, share with those who gaze upon them. Often I need only to capture, with a clear photojournalistic view, my subject’s desire for dignity and self-respect. My goal is not just to touch those viewers who are already sympathetic, but to command the attention of those who might just pass them by. My photo form follows its function.

Elizabeth Griffith, pregnant with her first child at the time, leaves the gravesite of her husband. Robert Griffith survived Vietnam only to die in the Scotia Mine Disaster when two methane explosions claimed 26 coal miner’s lives in 1976. Oven Fork Kentucky, located in Letcher County

A Lesson From My Time

In 1968, I was an advertising design student at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in Manhattan heading toward a career with the “Mad Men” on Madison Avenue of that era. But real world events intervened. The upstart students in my advertising design course arranged a class where we reversed roles with these ad men/our instructors. We assigned them to visually respond to the Bob Dylan song, “Something is happening but you do not know what it is, do you Mr. Jones?”

On the evening of April 4, 1968, we SVA students patiently waited on the top floor of the Young & Rubicam Advertising Agency, as the Carousel projector hummed, for our instructors to make their illustrated presentations about Bob Dylan’s song. After a delay, an instructor reported, “I have sad news, Martin Luther King has been killed.” Hardly a word was said as students and instructors alike quickly packed up. I headed to my Lower East Side 6th floor walkup apartment on the Lexington Avenue subway line at 14th St. Scrawled is still wet red letters on the grimy white tiles as I exited the station was this statement, “The Last of the Nonviolent Men are Gone, Arise and Kill Whitey, The Eternal Target.”

At SVA I had the good fortune to take a photography class designed to prepare future art directors to thoughtfully advise professional photographers to competently execute an ad concept we conceived,

photographically. The core of this instruction, in one word assignments, from our instructor, Paul Elfenbein, required each of us in the class to tap into our personal point of view while exposing one roll of 35mm Kodachrome slide film for each weekly assignment. One other key instruction was we were only allowed use a 55mm normal lens, requiring us to usually photograph our subjects at close range. For me, a very shy individual, this requirement opened my world. The camera gave me the best excuse to engage with subjects I found to be worthwhile. I had to introduce myself, let them know why I wanted to take their picture, and if I was lucky the favor would be exchanged with a collaborative photo session. But it took a lot of photo classes for me and my classmates to learn how to translate what we felt about our subjects into photographs that also expressed who we were as individuals behind the camera.

In the days and weeks after Martin Luther King’s and then Bobby Kennedy’s assassination, I continued to photograph for my class in the Lower East Side of Manhattan where I lived. Soon, my photo instructor put me in touch with Milton Glazer, the Art Director at New York Magazine and boom, my first published image was on the cover of its May 1968 issue. On November 20th, the Farmington Mine exploded, killing 78 coal miners. About to finish at

SVA, it was then I applied to become a VISTA Volunteer, seeking in this way an opportunity to rub shoulders with coal miners, who then worked at the most dangerous job in the United States.

By 1969, I was located in the Cumberland Plateau region of Tennessee, mostly meeting miners sidelined by black lung disease as Richard Nixon signed the Mine Safety & Health Act (MSHA) and the Occupational Health & Safety Act (OSHA) into law with the EPA formed by 1970. But it was the murder of Jock Yablonski, a United Mine Workers leader, along with his wife and daughter at their Clarksville, Pennsylvania home on December 31st, 1969 that resulted in five years of creatively formative work for me. First as the graphic designer and photographer for Miners for Democracy (MFD) and later when that successful campaign to unseat the corrupt UMWA leader, Tony Boyle from the presidency of that union, opened the door to becoming the photographer for the United Mine Workers Journal, a position I held until 1977. By then, the foundation for my 50 year path as a photographer of dangerous occupations had been laid, first as an SVA student; as Vista Worker photographer; Miners for Democracy activist with camera; and then as the photographer for the UMWA. My path forward has always required me to seize new photo assignment opportunities in the midst of political resistance.

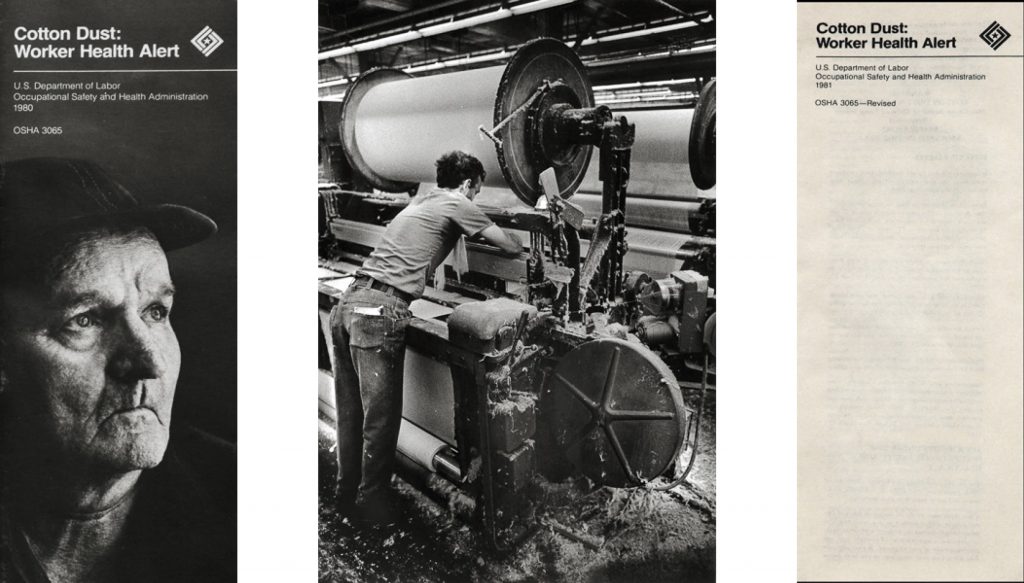

In 1977, Gene Thornton, in a New York Times review of my exhibit, In Our Blood, Coal Miners in the 1970s, at Gallery 1199 of the Hospital Workers Union in NYC, said I was one of the most important emerging photographers in the United States then. But one year later he called me an agitprop artist in a review of my Rise Gonna Rise, A Portrait of Southern Textile Workers exhibit. The impact of Ronald Reagan’s presidency had quickly shifted this nation’s political ground. Then Thorne Auchter, Reagan’s first appointee to OSHA recalled 50,000 Cotton Dust Standard brochures, destined for cotton mill workers, illustrated with my photographs. Auchter

said, the photo of an already dead cotton mill worker, Lewis Harrell, on the cover, was too inflammatory. Auchter republished the Cotton Dust brochure without any photos.

By 1998, I was invited by the American Industrial Hygiene Association’s (AIHA) Social Concerns Committee to create an exhibit documenting my first twenty years of photography. An exhibit titled, THE QUIET SICKNESS, A Photographic Chronicle of Hazardous Work in America was presented at AIHA’s annual meeting of 10,000 industrial hygienists in Washington DC in 1997. These occupational health professionals said to me numerous times that the exhibit reconnected them with their original motivations for entering the industrial hygiene profession. The book of the same name, published by AIHA PRESS came out a year later. By that time, the exhibit

and book were hosted at the Harvard School of Public Health, including touring the exhibit throughout all the New England States.

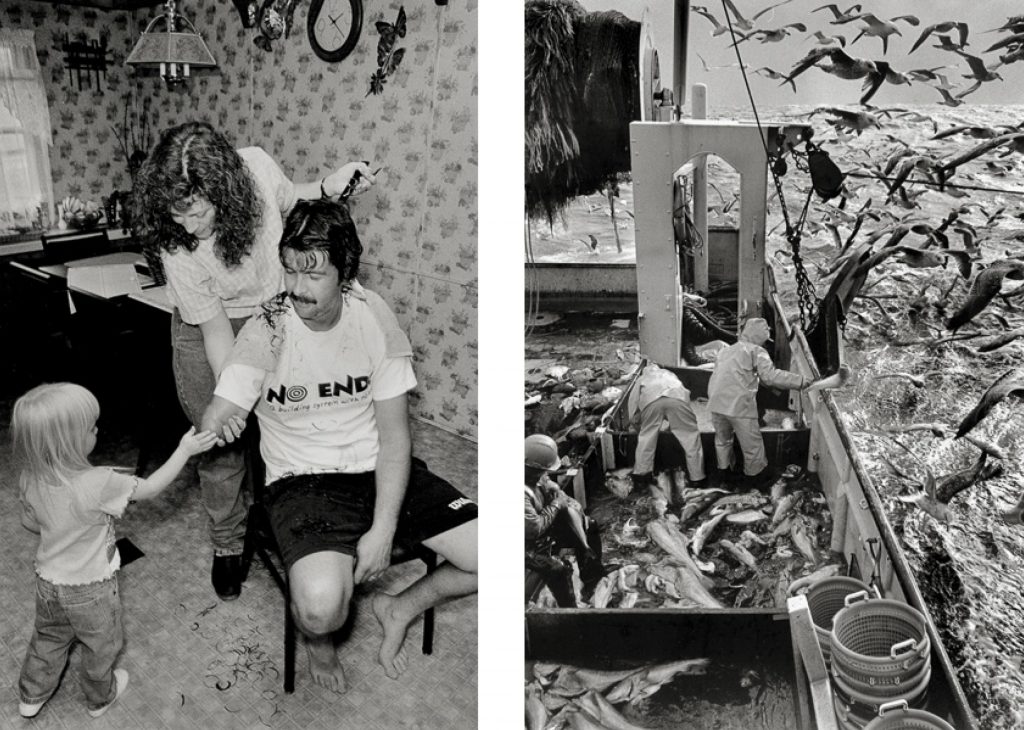

In the twenty years since, I continue to be a Visiting Scholar at the Harvard Chan School of Public Health (HSPH) with my photo projects benefitting from the scientific training of fellow Visiting Scholars and their networks that have offered collaborative projects in New England such as my exhibit: THE PRICE OF FISH, Commercial Fishermen Loose Life and Limb in New England (funded by an Alicia Patterson Fellowship). That exhibit was already to tour when the 9/11 attacks occurred in Manhattan and Washington, DC.

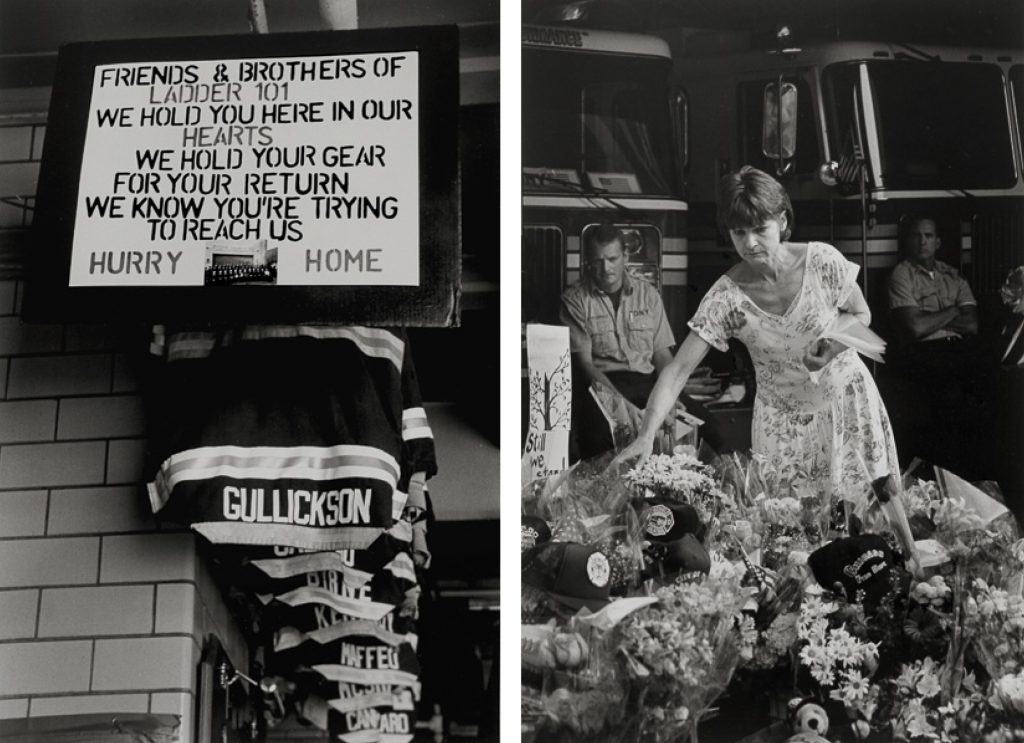

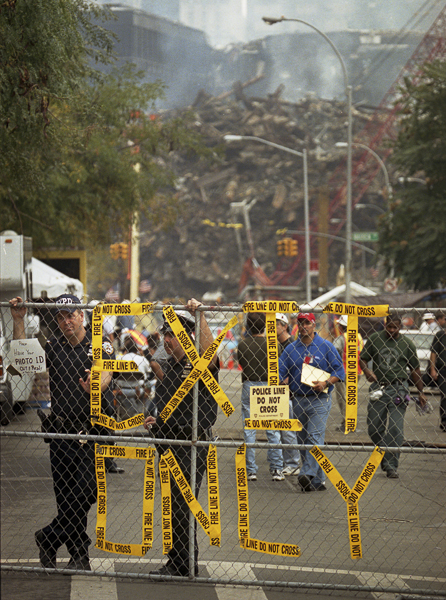

With THE PRICE OF FISH on hold, I traveled to Lower Manhattan on the first day the general public was allowed to return to Lower Manhattan and the perimeter of Ground Zero. Up to that point in my career I had done little work related to the hazardous occupation of firefighting and now 443 had died in and around the collapse of the Twin Towers. With no special access, I was limited to taking pictures of the can do attitude of the emergency responders, an inspiring sight I choose to shoot in color. But for my firehouse memorial tribute visits, black and white film was a far more appropriate choice to record this profound tragedy.

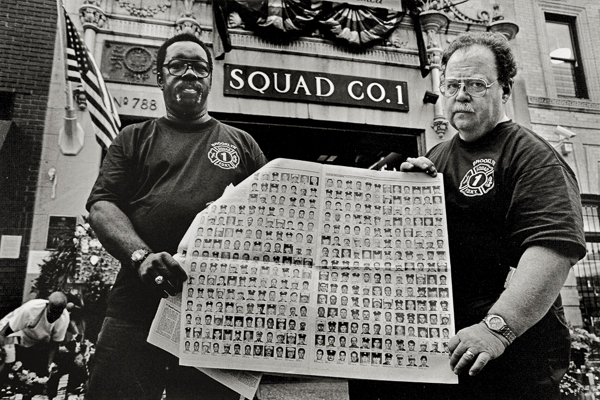

I found the citizens of New York City erecting memorials to the 443 brothers and sisters lost on September 1st, 2001 in rituals of unfathomable sadness. The motto of the fire company in Manhattan’s Theater District, that lost 15, was, “We Never Miss a Performance.” In Red Hook, Brooklyn I saw the turn-out gear of those still missing from the fire company and at the station house in Park Slope, retired fire fighters had returned to duty, looking through the New York Times double page spread to confirm for the first time their lost and missing brethren as residents paid their respects. “Because of You, I Lived,” wrote a neighbor who had been rescued.

While a very important and somber mission to document the loss of fire fighters throughout the city, upon returning to my home in Silver Spring, Maryland, I immediately began to formulate a strategy to photograph on Ground Zero itself.

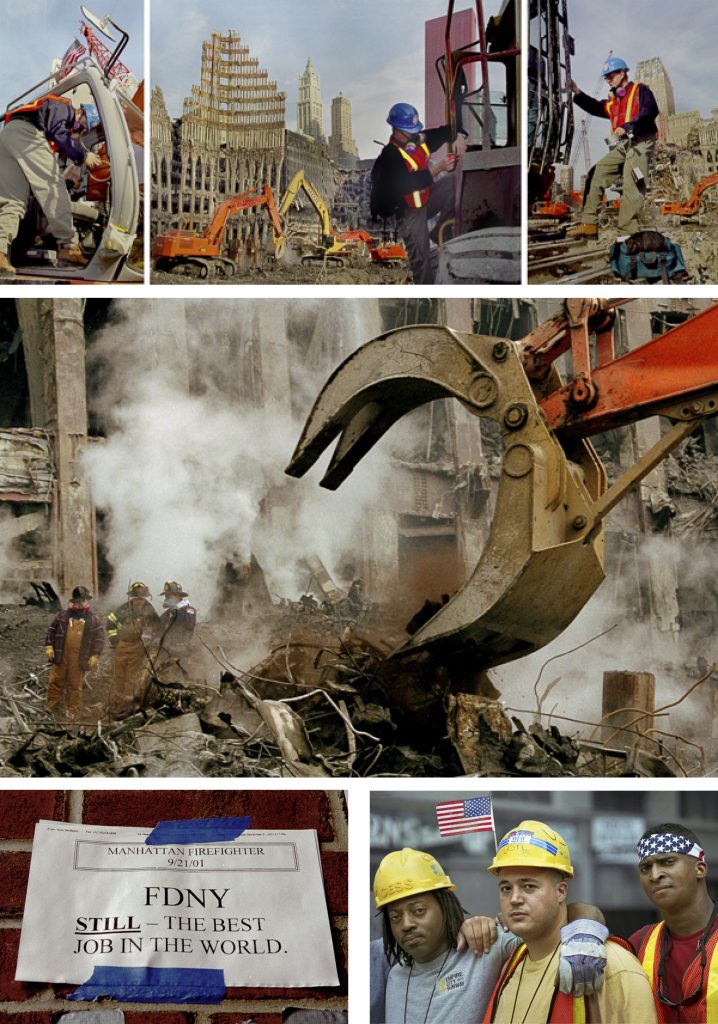

I learned the Health and Safety Department of the International Union of Operating Engineers (IUOE), who were running the heavy equipment to open up “The Pile,” had become quite concerned about the air quality on Ground Zero, not only outside the cabs of their heavy machinery, but inside where the operators controlled this vital rescue recovery equipment.

I was granted an assignment with access from the IUOE to accompany Aron Ondu, who was an Industrial Hygienist and a member of that union as he made these critical air quality tests. For the better part of a day I photographed Ondu making those tests but also allowing me to aim my camera wherever emergency responders were working on the site as it still continued to burn. Those air quality tests contradicted the earlier pronouncements of EPA Director, Christy Todd Whitman, that the air and smoke being emitted from Ground Zero was safe.

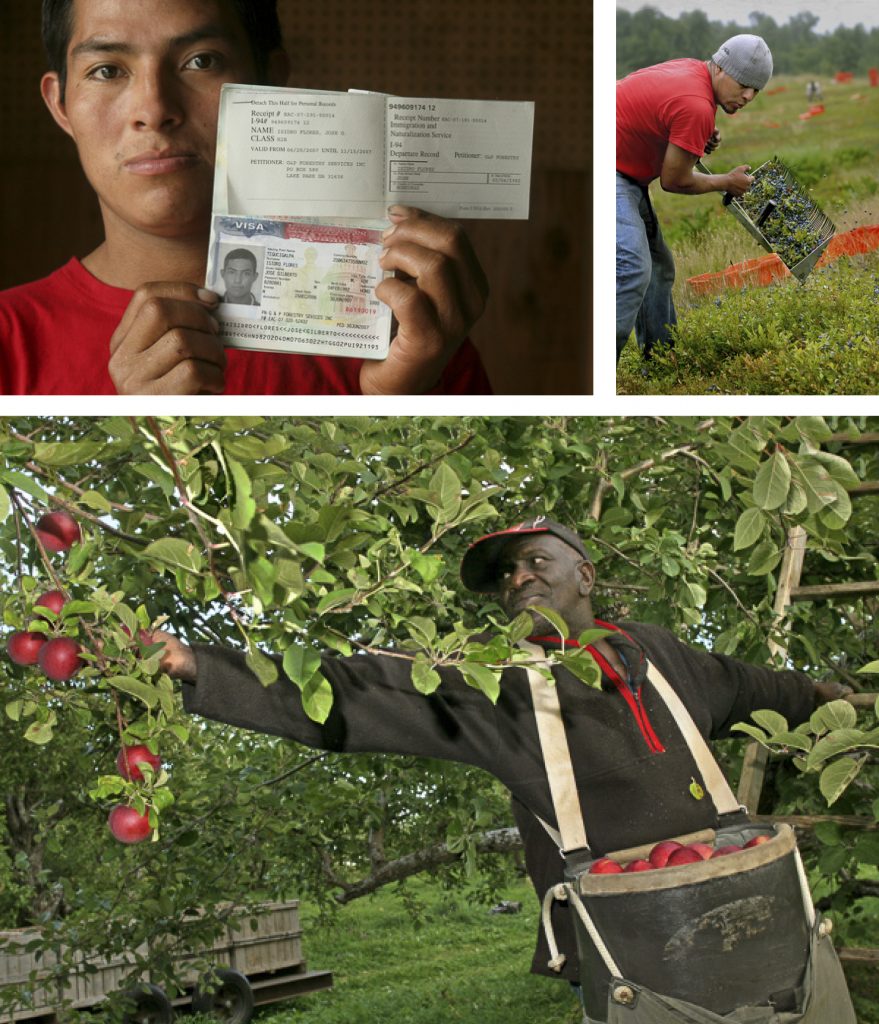

The exhibit that resulted was called: WHEN DUTY CALLS, A Memorial Tribute to 9/11 Emergency Responders. THE FARMWORKER FEEDS US ALL, The Labor and Health of Migrants in Maine, was an exhibit I created in 2007 after documenting all of Maine’s hand-harvests. I photographed Salvadorian tree planters and broccoli cutters working right next to the

Canadian border, over half of which had legal documentation and were quite proud to show it. I made pictures of Mexican and Native Americans harvesting wild low bush blueberries at the coast in Washington County. In the Fall I photographed Jamaican apple pickers and cranberry harvesters in Madison County bogs. These migrants were farmers back in Jamaica during Maine’s Winters. I shot this exhibit with digital equipment for the first time, allowing me to show my subjects how they looked in my camera as I was photographing them. This exhibit returned a year later to most of

these same workers, presented at local libraries or community centers. I also began to request farmworker’s cell phone numbers or email addresses enabling me to thank them by providing them my digital photos in

exchange for granting permission to take their picture. This exhibit also showed the work of the Maine Migrant Health Program (MMHP) that provided free or low cost health care services to farmworkers from mobile clinics that arrived at harvest sites or labor camps. The trusting relationship the MMHP developed over many years transferred to me, allowing me to photograph the provision of health care services, but also to later follow these same workers to their work sites or camps after work.

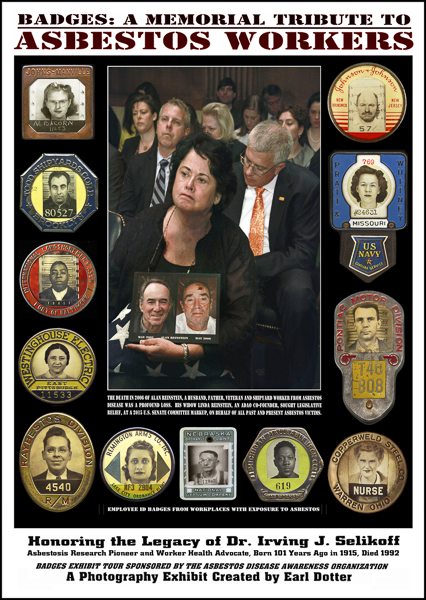

In addition, to my current retrospective exhibit: LIFE’S WORK, A Fifty Year Photographic Chronicle of Working in the U.S.A. and book of the same name my exhibit, BADGES: A Memorial Tribute to Asbestos Workers represents an ongoing collaboration with the Asbestos Disease Awareness Organization.

ADAO advocates for the 15,000 victims that succumb to asbestos related diseases every year, including 9/11 emergency responders and the public exposed by asbestos released into our environment in the U.S. ADAO also seeks enactment of a total U.S. ban on asbestos manufacturing and product use. The workplace photo ID Badges included in the exhibit and poster below personalize asbestos victims, naming the companies that harmed them while employed mining, manufacturing or using asbestos at work.

…

I first saw the image of Elizabeth Griffith in the summer of 1986 while interning at a newspaper in Charleston, WV. It’s still among the greatest photographs I’ve ever seen.

Wonderful article, thanks Earl for leading us so ably through your career.

Earl Dotter replies:

Regina

Creating this look back at my path with the camera has focused my view forward now. I still pickup the camera with enthusiasm and on rainy days it is a great diversion to look through the proofs from the previous 50 years. I still discover many fresh images that are now only possible to print digitally and had to be overlooked when I was in the darkroom

Pingback: Pictures That Speak | Earl Dotter

Pingback: Blog | Earl Dotter