The Women Behind the Black Panther Party Logo

By Lincoln Cushing

All graphics have a story to tell. Some logos of 20th century political movements have become recognized the world over – the peace symbol, designed by Gerald Holtom; the United Farm Workers logo, created by organizers Cesar Chavez and his cousin Manuel; and the Black Panther Party logo, designed by…whom?

That would be Dorothy Zeller.

The Black Panther Party logo’s roots go back 1966, with the Lowndes County Freedom Organization in Alabama (also called the Black Panther Party). It was a political party running progressive African Americans for office, and state electoral law required such groups to have a logo on their ballot to make it easier for illiterate voters. Although there was no formal organizational relationship between that Black Panther Party and the subsequent Black Panther Party for Self Defense organized in Oakland, California, several figures – including SNCC field organizer Stokely Carmichael – served to bridge these two key organizations in the Black power movement.

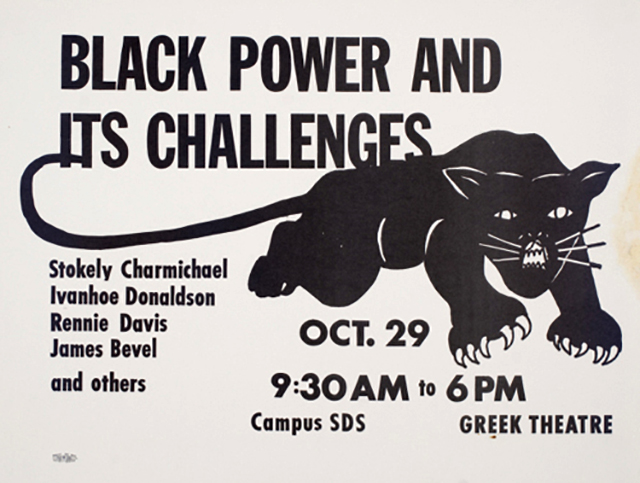

In a speech delivered at the 1966 S.D.S.-sponsored “Black Power and its Challenges” conference at U.C. Berkeley, Carmichael said:

We chose for the emblem a black panther, a beautiful black animal which symbolizes the strength and dignity of black people, an animal that never strikes back until he’s back so far into the wall, he’s got nothing to do but spring out. Yeah. And when he springs he does not stop.

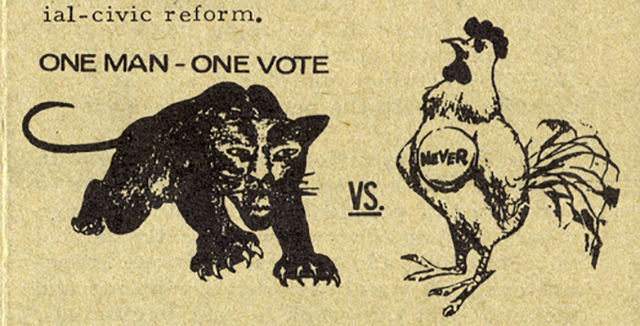

The all-white Alabama Democratic Party’s graphic was a white chicken. According to civil rights veteran Scott B. Smith, Jr., a clenched fist had also been proposed as a graphic for the LCFO – but was rejected in favor of a “black cat” with superstitious powers.

But the graphic first used in that campaign bears little relationship to the streamlined, powerful graphic associated with the BPP. Enter Dorothy “Dottie” Zellner. I interviewed Dorothy in 2016 and she explained how it happened:

I was working in the Atlanta office of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee when I was approached by Stokely Carmichael because he knew I’d gone to the High School of Music and Art. He’d gone to a sister school, Bronx High School of Science. He asked me to draw a panther for the Lowndes County Freedom Organization campaign. I said no, I wasn’t that capable an artist.

Stokely asked my then-husband Bob Zellner to go to the local zoo and take some photos of the panther there, but they weren’t any help.

Bob Zellner was a minister’s son from Alabama, and he reflected on this event in a 2006 listserv discussion of veterans of the civil rights movement:

One day [James] Forman told me to get a SNCC photographer and go with him to the Atlanta Zoo and take a picture of a black panther. “He is lazy so you may have to poke him to make him growl,” Forman said. “Bob, you poke him and the photog can get a growl, maybe. See what you can do.” We got several shots and returned to the office. Forman took the film into the dark room and came back with wet photos. He asked everybody in the office, “Who can draw?” Dottie said, “I went to art school, I’ll take a shot at it. Forman, what kind of picture do you want?”

Forman said, “Make him growl and show some teeth.” I don’t know why we always referred to the panther as “he.” He could have been a she, as far as we knew. Dottie refined the first rough drawing of the now famous Black Panther. Dottie drew it so it would reproduce well in black and white — a panther with curled tail, bared teeth, and pronounced whiskers, ears perked up.

Dorothy further explained:

The next time Stokely asked, he showed me a rough line drawing of a panther – it really looked more like a cat – and asked if I’d try again, so I did. I cleaned it up, added better whiskers, and made it black. at his request.

The next time I saw it, that image was on TV sometime in 1967 – I was shocked!

Many years later I learned that the drawing Stokely had given me was done by Ruth Howard, and was based on a school mascot of one of the HBUC’s in the Atlanta area. [That was Clark College, now Clark-Atlanta University]

The panther name and logo was then taken to the San Francisco Bay Area by community activist Mark Comfort when he formed the Black Panther Project of the Oakland Direct Action Committee.

Bob Zellner concluded his recollection:

The symbol became smoother and more stylized with age. When I wrote about this… I commented on the irony that Dottie, a white northern woman, [was one of the artists involved in drawing] the first black panther.

Even after the panther entered the Bay Area, it remained restless. Although it was used widely in its current form, it was also modified depending on graphic needs. Movement graphic scholar colleague Lisbet Tellefsen and I had noticed that several “official” panthers were… different, and began to track down the artist.

That would be Lisa Lyons. In a 2016 interview, Lisa explained her role:

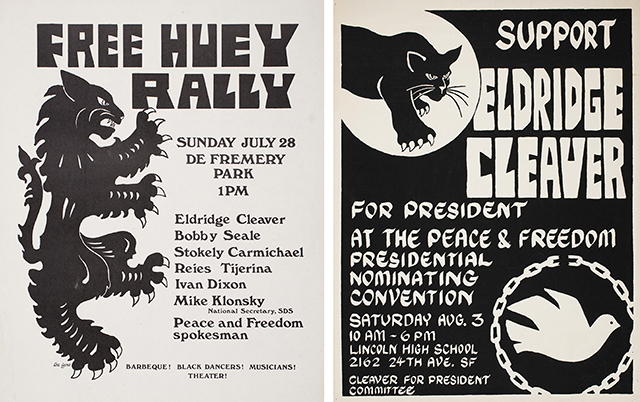

We chose the Lowndes County Freedom Organization panther for Black Power Day materials since it was already widely recognized nationally as a symbol of black power by the fall of 1966. My husband Kit and I were active members of the Independent Socialist Club in Berkeley, and we also made use of the panther symbol in ISC publications at the time of our work on the 1966 SDS Black Power Day conference. For example, see the cover of an SDS position paper published by the ISC for distribution on Black Power Day and a later ISC leaflet we distributed in Berkeley in the immediate aftermath of the Panthers “inaugural” demonstration in Sacramento.

We used the standard panther in a variety of other ISC and Panther publications in 1966 and 1967. For example, a poster for an ISC/Black Panther Party rally in defense of the ghetto uprisings and a label used for cans for fund raising for the Panthers, and a variety of Panther-related buttons.

I did make various small modifications of the panther symbol from time to time, depending on the size of the publication, etc., (including inadvertently changing the number of claws at least once.).

From ’67 through ’69, we also published other cartoons and buttons that morphed the basic design in more substantial ways.

I thank these three women – Ruth Howard, Dorothy Zellner, and Lisa Lyons – for their heretofore untold role in creating one of the most powerful icons of community self-defense and empowerment of the 20th century.

Images:

Detail, interior panel of brochure for the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, circa October, 1966; image courtesy H.K. Yuen Social Movement Archive collection

Flyer for SDS “Black Power and its Challenges” conference at UC Berkeley, October 29, 1966; image courtesy H.K. Yuen Social Movement Archive collection

Poster for SDS “Black Power and its Challenges” conference at UC Berkeley, October 29, 1966; poster courtesy Lisbet Tellefsen collection, image by author.

Poster for rally for Eldridge Cleaver for President, San Francisco, August 3, 1968; Docs Populi digital archive

Free Huey Newton rally, Oakland, July 28. Poster courtesy Lisbet Tellefsen collection, image by author.

A version of this piece first appeared in Design Observer 01 Feb 2018

Appreciating the consistent work of stansburyforum. More Power to you.

As far as I know, this was initially a symbol for the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, AL, which ran candidates for various county offices. Alabama law required a symbol for political parties, maybe because there were literacy issues. The “regular” Democrats had a rooster as its symbol. The black panther was an animal present in Alabama at the time, so they picked it.