A More Perfect Union: How Labor Paved Way for Employer-Sponsored Health

By Lincoln Cushing

“Are you ship shape?” brochure about ILWU member health testing; 1951. Courtesy the ILWU archive, source of original unknown

And, cousin, I’m a union man” – Warren Zevon, “The Factory”, 1987

For more than 60 years, millions of Americans have gotten health care insurance through their work. Despite employment changes in the American economy, that sort of coverage is still enjoyed by more than half of the non-elderly population. But it wasn’t always that way. The hard work of organized labor was instrumental in making employer-sponsored health coverage a cornerstone of the human services safety net.

One benefit of the Progressive Era (1890s-1920s) was that large companies had to offer some form of industrial health care for workers. That made good business sense, since an injured worker isn’t very productive. But what happened if you broke your arm at home, or your kid got sick? You were at the mercy of fee-for-service medical care.

The first employer-sponsored health insurance is usually noted as 1929, when a group of Dallas teachers contracted with a hospital to cover inpatient services for a fixed annual premium.

The large federal construction projects during the Great Depression boosted support for expanded occupational health care. When industrialist Henry J. Kaiser got the contract to finish Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River in Washington in 1938, he also had to care for the thousands of workers in this remote worksite. He brought in Sidney Garfield, MD, who’d finished a successful industrial care program for the Colorado River Aqueduct project in Southern California. At the Mason City Hospital, Dr. Garfield worked with the unions to create one of the first family plans. It wasn’t insurance, it was health care offered for a prepaid amount. For 50 cents a week, workers (spouses and children cost a small amount more) were guaranteed medical care. That comprehensive, voluntary, and affordable health plan would be replicated during World War II for the 190,000 workers and their families in the Kaiser shipyards.

But this was an anomaly. Most American workers had nothing remotely close to a nonindustrial health care plan, even in the booming years after the war. That would change in 1948 and 1949 with two key labor law rulings.

In late September of 1946, the union at Pacific Coast Steel Co., Local 1069, in the San Francisco Bay Area selected the Permanente Health Plan (now called Kaiser Permanente) for its members and requested that employers provide payroll deductions for health care. Bethlehem Steel Company (which acquired Pacific Coast Steel in 1930) disputed their right to make such a decision. The union brought the issue to court, and won. The case of (BOLD) W. W. Cross & Company, Inc. v. United Steelworkers of America, CIO decided June 17, 1948, found the company had violated the National Labor Relations Act by refusing to negotiate on the terms of a group health and accident insurance plan.

That next year the U.S. Supreme Court ruled fringe benefits were an appropriate subject for collective bargaining under the NRLA after reviewing the case of Inland Steel Co. v. National Labor Relations Board, which established a precedent for union contracts regarding hospital and surgical benefits for employees and their dependents.

The Inland Steel case first emerged in late 1947, when the NLRB arranged hearings on two cases involving the CIO-Steelworkers. One case concerns Inland Steel company plant at Indiana Harbor, Ind., and Chicago Heights, Ill.; the other the W. W. Cross and company of East Jaffrey, N.H. In each case, NLRB trial examiners ruled that the employers were guilty of unfair labor practices in not consulting the Steelworkers, with which they held contracts, when they put insurance and pension plans into effect. The examiners in both cases directed the companies to bargain with the union on the type and extent of these plans.

On April 14, 1948, the NLRB ruled that employers are legally bound to bargain on pension plans with unions whose officers have signed Taft-Hartley affidavits that they are not Communists. The United Press news coverage noted:

“…the far-reaching decisions could put CIO President Philip Murray and some other high union officials in an awkward position. Murray and several other top labor leaders have refused to sign the non-Communist affidavits. But they are now engaged in a drive to win pension plans… The NLRB split 4-to-l on its verdict that pension plans are a form of wages, on which the Taft-Hartley act requires employers and unions to bargain collectively. The case involved the Inland Steel Co., and the CIO United Steelworkers, which Murray personally heads.”

The requirement for non-communist affidavits would remain through the Dwight D. Eisenhower administration; in the beginning of 1959 he even proposed extending it to employers. But in the fall of that year he signed the new Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (Landrum- Griffin Act) amending Taft-Hartley, which included a repeal of the affidavits.

Corporations followed the Inland Steel case closely. Charles E. Wilson, president of General Motors, was quoted as saying:

“The inclusion of health and welfare plans within the area of collective bargaining can only create new and unexplored areas of industrial disputes, difficult —if not impossible—to solve.”

Inland Steel appealed, but on September 23, 1948, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the NLRB position [in 170 f(2d)247] and ordered Inland Steel to bargain with the CIO union concerning retirement pension plans, a ruling that applied to all companies in interstate commerce where a union is the recognized bargaining agent of the workers. In 1949 the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the decision. Although denial of a hearing does not formally constitute Supreme Court approval, the issue was effectively settled.

Labor and health policy scholar Marie Gottschalk noted this breakthrough in her 2000 book The Shadow Welfare State: Labor, Business, and the Politics of Health Care in the United States, the Inland Steel case introduced a period where “labor and management waged bitter battles over how much money employers should contribute to employee benefit plans, the items to include in these plans, and whether dependents should be covered.” But the door had been opened, and hundreds of thousands of working people benefited.

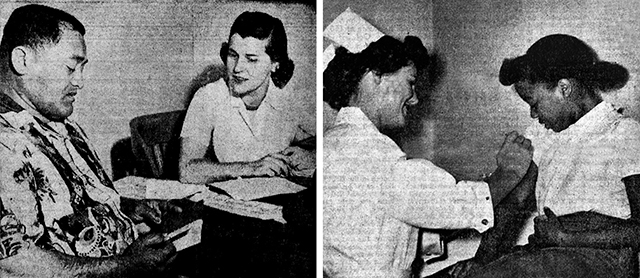

Left: “Anne Waybur of the ILWU Research Department interviewed more than 125 longshoremen, clerks, foremen and their wives in San Pedro, Calif., to find out what they think of the Permanente Health Plan coverage and service.” The Dispatcher, 1/5/1951. Right: Permanente pediatric clinic at 515 Market St, San Francisco – nurse giving Patricia Nisby, daughter of ILWU Local 10 member Wiley Nisby, a shot. ILWU Dispatcher, 1950-10-13. Detail from “Welfare is Porkchops”

In 1949 the International Longshore and Warehouse Union approached the Permanente Health Plan about covering their membership. Permanente and the ILWU had been in discussion since 1945, but the Inland Steel ruling made the leap possible. Permanente was attractive to the ILWU for its racially integrated facilities and labor-friendly record during the war.

The January 6, 1950, ILWU newspaper The Dispatcher announced the new Permanente Health Plan, and by year’s end, 90 percent of eligible members had signed up.

When the plan began, there was a big rush for treatment of such illnesses as hernias and hemorrhoids, conditions the men had suffered with and lived with for many years. They hadn’t been able to pay for medical care on their own. A March 10, 1950, article in The Dispatcher put it this way:

“The Welfare Plan is the greatest thing since the hiring hall.” That’s the opinion of D.N. (Lefty) Vaughn, Local 13 longshoreman, hospitalized here under Permanente. Vaughn told Local 13 visitors last week that if it wasn’t for the Welfare Plan he would have had to sell his home to pay for the major operation he’s getting for nothing through the Plan.

An editorial three weeks later further explained:

“Life can be beautiful if you’re healthy is the way the ad men put it. There’s no doubt they’ve got a point, though it’s oversimplified. Health is no fringe issue, not when you are required to make a choice between an operation which will allow you to go on working and living, and the home you must sell to pay for that operation. Longshoremen no longer have to make such choices. More than one home has been saved since the medical coverage section of the Welfare Plan became effective.”

The two rulings fundamentally shifted organized labor’s role in defending and expanding workers’ rights. Gottschalk further describes the impact:

“The myth of the consensus years of labor-management relations in the 1950s obscures how contested an issue benefits remained at the bargaining table. In 1949, health and welfare issues were central in 55 percent of all strikes; in the first half of 1950, 70 percent of all strikes were over these issues.”

While it’s true that the benefits of Inland Steel only applied to organized workers in larger industries, leaving out agricultural labor and smaller shops, it was a major step forward in building public expectations that medical care be affordable and accessible.

Thank you, organized labor – you not only brought the weekend to our regular work week, you brought us the employer-sponsored health plan. And on this particular Labor Day weekend, let’s remember and honor the gains made by unions.

Special thanks to ILWU archivist Robin Walker, who has put newspapers from 1932 to present online.

A price was paid for these plans: unions were no longer interested in fighting for universal health care. If you weren’t part of a union that had the power to negotiate a good plan you were left without one.

Pingback: A More Perfect Union: How Labor Paved Way for Employer-Sponsored Health Care « A History of Total Health | Kaiser Permanente History Blog