Debating the Working Class 50 Years Ago in SDS: Lessons for Today?

By Joe Allen

Fifty years ago in August 1966 delegates from across the United States attended the annual Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) Convention in Clear Lake, Iowa. Located in north central Iowa and held at a local Methodist camp, it provided a bucolic setting to debate its future.

SDS was at a crossroads in 1966. It had evolved into the largest radical student organization in the United States and was going through a major membership and political transformation, according to SDS historian Kirkpatrick Sale.

For attendees, Clear Lake convention—350 delegates from 140 chapters meeting from August 29 to September 2—was symbolic. Leadership was now transferred from the original members to the newer ones; from those born in the left-wing traditions of the Coasts, to the middle-American activists. It was the ascendance of ‘prairie power.’

The biggest topic at the convention was what direction SDS should take.

The small delegation from the Independent Socialist Clubs (forerunner of the 1970s International Socialists) made a quite radical proposal to the convention.

“The socialist view of the working class as a potentially revolutionary class is based upon the most obvious fact about the working class, that it is socially situated at the heart of modern capitalism’s basic, and in fact defining institution, industry,” wrote Kim Moody, Fred Eppsteiner and Mike Pflug in Towards the Working Class: An SDS Convention Position Paper (TTWC).

It was one of the first attempts to orient the New Left around the rank and file struggles of U.S. workers. Stan Wier’s pamphlet USA: The Labor Revolt was the road map that socialists used to understand the burgeoning rank and file rebellion that began in the mid-1950s away from the media spotlight but by the mid-1960s was visible for all to see. It was front-page news.

The settings are very different, but are the debates from a half-century ago relevant today?

The year 1966 may best remembered as the year in which during the “Meredith March Against Fear” in Mississippi, SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Toure) declared, “What we need is black power.” That slogan captured the imagination of a generation of young Black revolutionaries frustrated by the broken promises of U.S. liberalism who demanded a radical transformation of society.

Many other long oppressed peoples followed—Women, Chicanos, Native Americans, Gays and Lesbians, for example—took up the demand for “power” to liberate their communities.

Moody, Eppsteiner, and Pflug were no less interested in the questions of power and liberation. All three were veterans of the civil rights movement in Baltimore, and active in or around the Baltimore SDS at Johns Hopkins University. Moody was also active in the Baltimore SDS’s community project, U-Join (Union for Jobs and Income Now). Moody and Eppsteiner were members of the Independent Socialist Clubs (ISC) while Pfug was a member of “News and Letters”.

The ISC emerged out of a split in the rightwing of the Socialist Party led by the aging Norman Thomas. The political inspiration for the ISC was Hal Draper, a veteran revolutionary socialist and author of the extremely popular pamphlet “The Mind of Clark Kerr.” It was an examination of the president of the University of California system, and his ideas for the modern university. It became the bible of the Free Speech movement at Berkeley.

Later Draper also popularized the term “socialism from below” in the magazine New Politics, reclaiming the revolutionary democratic spirit of Karl Marx’s belief that socialism could only be achieved through the “self-emancipation of the working class.” “Socialism from below” was a quick and clear phrase to distinguish revolutionary socialist politics from the “socialism from above” of Social Democracy and Stalinism.

In an era when a revolutionary was thought of as a guerilla fighter with an AK-47 fighting in the jungles of a distant country, support for such “classical” Marxism was certainly going against the current.

The TTWC authors called themselves “radicals who support the concept of Black Power” but looked at the question of power and liberation from a different angle. “We, socialists and radicals, look to the rank-and-file workers as our potential allies,” they declared. A powerful example of this potential was the machinists’ strike that crippled passenger airline travel across the United States.

The TTWC authors wrote, “For those who have doubts,” about the willingness of workers to struggle for progressive ends, take a look at the recent airline strike of the International Association of Machinists (IAM). Not only did the strike hold out against the threats of a congressional injunction; but the rank and file had the guts to flatly reject a settlement pushed by President Johnson himself. A interesting political side light is that four IAM locals have recently called for a break with the Democratic Party and the formation of a third party.”

They emphasized, “Keep in mind that this was a struggle that occurred without the benefit of radical organizers; it was, in many ways, a spontaneous act.”

Relating to the labor movement but almost exclusively as outside supporters had its limits, according to the ISC authors:

“We believe that supporting strikes and organizing workers for independent unions or even existing unions is good, but it is not enough. Furthermore, there is a sort of hierarchy of value in these activities. Working on a union staff may provide good experience for a student or ex-student, but it cannot be a place from which political work can be done.”

They wanted to make clear to the delegates that they weren’t denigrating union organizing “but that you cannot do serious radical political work from that position.”

The TTWC authors argued, “SDS, as an organization, and SDS members should orient towards the working class as the decisive social sector in bringing about the transformation of American society.”

This was serious work that the TTWC authors didn’t want “romanticized” or seen as a “moral virtue” for those willing to organize in the industrial workplaces.

The setting was very different in 1966 for debating a rank and file perspective than today. Unions were major institutions—‘Big Labor,’ as it was called then—in U.S. economic and political life. The rank and file rebellion was causing major political concern and a crisis for the entrenched leaders of the U.S. trade unions.

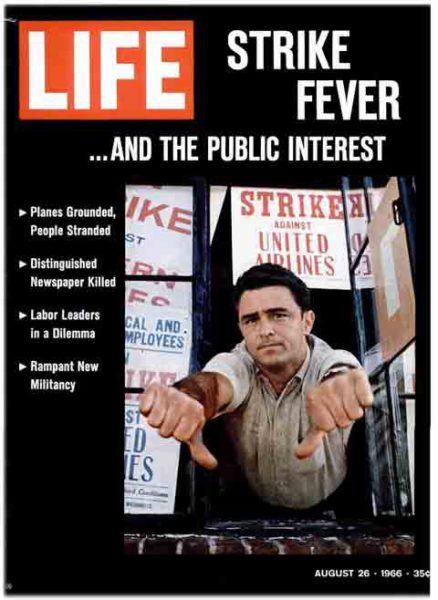

The front cover of Life magazine captured the setting well with a headline of “Strike Fever” with a picture of a striker voting no with two thumbs and a side bar decrying “Labor Leaders in Dilemma” and “Rampant New Militancy.”

Despite the favorable circumstances, TTWC co-author Kim Moody told me, “Our position paper received little attention as the main underlying business was the transition from the ‘old guard’ leadership to the new ‘generation’ that was flooding SDS. We had hoped to influence some of the younger people entering SDS. “Toward the Working Class” actually appeared in New Left Notes in the Sept 9 issue –after the convention.”

It lost out to Carl Davidson’s proposal for a new student syndicalist movement that emphasized SDS’s focus primarily on the campuses. TTWC has almost been entirely ignored by historians of the New Left with the notable exception of Peter Levy’s “The New Left and Labor in the 1960s”.

While it was wrong to expect SDS to completely reorient itself in such a short period of time—there was still plenty of reason for a student movement to grow especially with the burgeoning antiwar movement on the campuses that SDS was in the thick of— yet, one cannot help but look back and feel that there was a lost opportunity here.

When the various communist and socialist organizations (that emerged from the New Left in the late 1960s and early 1970s) made a turn towards organizing in the industrial working class during the 1970s, was it too late?

During the last four decades the gut-wrenching changes to the industrial working class significantly weakened, if not destroyed, the once mighty industrial unions in many parts of the U.S. industrial economy. The left that attempted to build in the industrial unions were marginalized, if not destroyed by these changes.

However, one of the offspring of the political work of the International Socialists was a reform movement within the Teamsters in the 1970’s. Teamsters for Democratic Union (TDU) played a major role in the election of the Teamsters first reform president in 1991, the UPS strike of 1997, and the recent near-defeat of incumbent Teamster general president James P. Hoffa.

Today, once again a new generation of radicals is discussing the question of oppression, power and radical change. How do we have a similar debate today that SDS had in 1966 but with a broader audience?

The absence of even a small left in the industrial unions in the upper Midwest is part of the reason that Trump triumphed in the Electoral College. The popularity of Bernie Sanders among industrial workers and the victories of Zuckerman’s reform campaign in the Midwest, I think demonstrates this.

As I wrote in Jacobin of last December:

“For the broader labor movement and left in the United States, the Teamsters’ elections should counter some of the impact of Trump’s victory and with it much inane discussion of the American working class. A befuddled Paul Krugman wrote in his most recent column, “To be honest, I don’t fully understand this resentment [that elected Trump].” Yet the states that gave Trump the presidency also voted overwhelmingly to toss out Hoffa.”

Today the modern industrial economy revolves around the logistics industry. As Kim Moody wrote last year:

“Eighty-five percent of the nearly three-and-a-half million workers employed in logistics in the United States are located in large metropolitan areas–inadvertently recreating huge concentrations of workers in many of those areas that were supposed to be “emptied” of industrial workers. There are about 60 such “clusters” in the United States, but it is the major sites in Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York-New Jersey, each of which employs at least 100,000 workers and others such as UPS’s Louisville “Worldport” and FedEx’s Memphis cluster that exemplify the trend.”

If Amazon makes good on its promise, by 2018 it will add another 100,000 workers to its U.S. workforce bringing the total number to over 200,000. It will be one of the largest employers in the United States and one of the largest non-union employers. A new generation socialist activists have to learn how to organize these workplaces.

A New Left is emerging in the United States. The millions who participated in the huge demonstrations that greeted Trump’s first weeks in office is the most visible and spectacular sign of this. The rapid growth of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) is one of the most visible signs of this along with widespread interest in general socialist ideas, history, and organizations. Moshe Marvit and Leo Gertner in the Washington Post capture the spirit of rebellion at the moment and advocate its spread to the workplace, “Though often overlooked in America, the workplace can be as much a focal point of resistance and protest as the streets.”

However, we shouldn’t underestimate the obstacles we face. We are challenged with the daunting task of creating a new socialist movement and a new industrial union movement virtually from scratch.

While I believe that the politics of “socialism from below” will be the most important political contribution to the formation of next New Left, we need to bury the legacy of Stalinism once and for all. I would argue that we need to begin modest campaigns advocating socialist ideas and organizing in the logistics industry in select cities.

Such an effort must begin modestly but they must begin. Trump’s triumph in the Electoral College demonstrates the peril of an absence of socialism in the industrial working class.

Former SDS Chicago organizer and ISC member Wayne Heimbach warns us about lost opportunities. “In 1966 it was the ISC people who had the high ground in SDS on working class politics. Within a year or two this would transfer over to Progressive Labor and its Worker/Student Alliance,” he told me. PL’s cartoonish and thuggish politics were one brand of the many varieties of Stalinism that came to dominate and wreck the post-1960s left in the United States.

Looking back on the debates at the 1966 SDS convention SDS leader Jeff Shero told Kirkpatrick Sale, “We wanted to build an American left, and nothing less than that”. The question today is the same, but I would add, What kind of American left do we want to build?

Pingback: Debating the Working Class 50 Years Ago in SDS: Lessons for Today? | 1960s: Days of Rage

I recall ISC’s paper and their role in SDS at that time. It was Trotskyist orthodoxy and didn’t capture the spirit of the times, a rising generational youth revolt. Which is why my paper won out over theirs–and it too celebrated the working class in its way, with a tip of the hat to the IWW. What was more important was the work of the SDS Praxis group in 1967, developing the theory of the new working class, ie, what we call the ‘precariat’ today.

If you google lulu and ‘Revolutionary Youth and the New Working Class’ you’ll find a collection I rescued from the memory hole.