MLK’s Advice on Strike Strategy Still Relevant Today*

By Rand Wilson

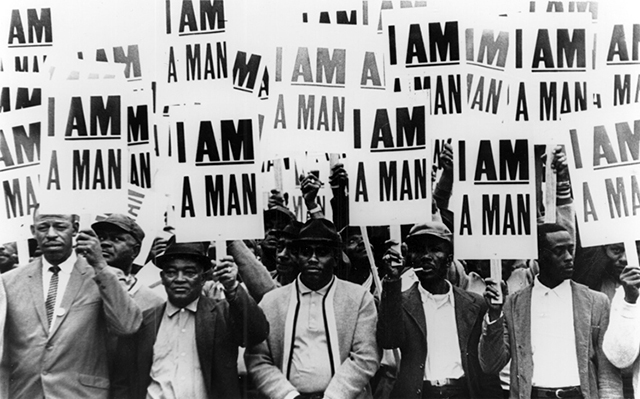

Striking members of Memphis Local 1733 hold signs whose slogan symbolized the sanitation workers’ 1968 campaign. Credit: Copley, Richard L., “I AM a Man,” I Am A Man, accessed January 18, 2017.

After 1965, Martin Luther King Jr’s thinking about poverty evolved from racial equality to more of a class perspective. He proposed a Poor People’s Campaign to challenge the government to end poverty and a broad coalition to support it. But building a coalition to back his program for economic justice proved more difficult than he imagined. It made his funders and even his closest advisors nervous. A proposed national march on Washington had to be postponed and King was growing frustrated.

Sanitation workers in Memphis, TN had been trying to get organized and win recognition from the city for years without success. After two workers were accidently crushed to death in one of the garbage trucks, a majority of the workers decided to strike on February 12, 1968 for union recognition and a contract.[1]

The strike had been going on for months with growing frustration. Incidents of violence were increasing, mostly provoked by the racist and brutal Memphis police.

King recognized that the strike provided with an opportunity to demonstrate how the civil rights and economic justice movements could come together at the local level. He proposed bringing the campaign to Memphis.

Expand the Strike

King first went to meet with the strikers in Memphis on March 18. He spoke to 1,500 workers and supporters. King was well received and the crowd’s mood was militant and eager for action.

King said, “If America doesn’t use her vast resource of wealth to end poverty and make it possible for all of God’s children to have the basic necessities of life, she too is going to hell.” And he went on to describe how their strike was part of new direction for the civil rights movement:

“Now our struggle is for genuine equality, which means economic equality. It isn’t enough to integrate lunch counters. What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn’t earn enough to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee?”

As the crowd cheered, King saw an opportunity to grow the movement by expanding the strike. He called for a general strike in the city of Memphis! Plans were made and a strike date was set. The tactical escalation was highly controversial.

Unfortunately, due to a freak snowstorm, the strike was called off. Amid growing threats to his life, King hurriedly left Memphis. However, he was not to be deterred and vowed to return.

Boycotts and economic action

King returned to Memphis on April 3, 1968 to support the strike again. At a rally with strikers and area clergy he gave his, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech — one of his most famous and fatefully his last.[2] This is the speech where King predicted his own assassination.[3]

However, the main subject of the speech was winning the sanitation strike. King advised they should use the power of the boycott to, “Always anchor our external direct action with the power of economic withdrawal.”

“We don’t have to argue with anybody. We don’t have to curse and go around acting bad with our words. We don’t need any bricks and bottles, we don’t need any Molotov cocktails, we just need to go around to these stores, and to these massive industries in our country, and say, “God sent us by here, to say to you that you’re not treating his children right. And we’ve come by here to ask you to make the first item on your agenda fair treatment, where God’s children are concerned. Now, if you are not prepared to do that, we do have an agenda that we must follow. And our agenda calls for withdrawing economic support from you.”

Making our pain, their pain

When workers go on strike, it almost immediately involves personal sacrifice. As the weeks and months go by, that sacrifice becomes real pain inflicted on the strikers and their families. King’s quote from his last speech is particularly relevant to most every strike situation:

“Up to now, only the garbage men have been feeling pain; now we must redistribute the pain. We are choosing these companies because they haven’t been fair in their hiring policies; and we are choosing them because they can begin the process of saying, they are going to support the needs and the rights of these men who are on strike. And then they can move on downtown and tell Mayor Loeb to do what is right.”

One day longer

King knew the importance of winning, of keeping spirits up and sticking together. He said, “We’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end. Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point, in Memphis. We’ve got to see it through.”

Solidarity forever

To the clergy and other civil rights supporters, King delivered a powerful message of solidarity: “And when we have our march, you need to be there. Be concerned about your brother. You may not be on strike. But either we go up together, or we go down together.”

Near the end of the speech, King used the “Good Samaritan” parable from the bible to implore everyone to make even greater sacrifices to help the workers win. He concluded with words that have an uncanny relevance to our time:

“Let us develop a kind of dangerous unselfishness… Let us rise up tonight with a greater readiness. Let us stand with a greater determination. And let us move on in these powerful days, these days of challenge to make America what it ought to be. We have an opportunity to make America a better nation.”

King’s strategic advice to the striking Memphis sanitation workers is still useful for workers seeking to improve their lives with direct action today. Once on strike, expand the struggle beyond the immediate company to its corporate allies and suppliers; use boycotts and economic action to involve supporters; transform the pain inflicted on strikers, to pain inflicted on executives, board members and investors; be prepared to stay in the struggle one day longer with “dangerous unselfishness”; and perhaps most importantly, winning requires placing the struggle in a larger context that challenges elected officials and government at every level to make America a better nation!

*Adapted from remarks by Rand Wilson on January 16, 2017 at the Capital District Area Labor Federation’s 20th Annual MLK Labor Celebration in Albany, NY. In nearby Waterford, NY there are 700 workers on strike at Momentive Performance Materials and in Green Island, NY, dozens of workers have been locked out at a Honeywell aerospace plant for more than nine months.

Footnotes:

[1] Memphis sanitation strike

[2] I’ve Been to the Mountaintop

[3] “Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!”

Mr. Wilson – how can you write about the Memphis Sanitatation workers strike and MLK and not even mention Rev. James M Lawson Jr. ? The strikers asked Lawson for help and leadership. Lawson and MLK discussed the importance of the strike and its larger significance. Lawson invited MLK to join him in Memphis. The strike tactics were Lawson’s.