When I reflect on Labor Day

By Robert J.S. Ross, PhD

When I reflect on Labor Day I think about time – time for work and leisure, and the time that spans the generations. How precious it is, and how time is, after all, all we really have. We celebrate Labor Day in September because we don’t celebrate it when most nations celebrate workers, that is May 1. And May 1 is all about the eight-hour day. Let me unpack that — briefly.

Grover Cleveland signed the federal legislation in August 1894 a few days after he had sent troops to brutally suppress the strike of railroad workers and Pullman sleeping car makers. Though 30 states had Labor Day holiday legislation, at the federal level Cleveland was trying to placate a constituency he had deeply antagonized. The bill chose September in part to avoid May 1 because May Day had become a day in which socialists and anarchists demonstrated their power and commemorated the deaths of the leaders of the Haymarket Strike and riot of 1886. Those 1886 events marked the start of serious agitation for the eight-hour day.

By 1938 that was achieved in federal law, and many unions and employers in fact use standard weeks of 37 or even fewer hours. Pause for a moment and reflect on the “Eight Hour” song from the mid-19th Century:

“We want to feel the sunshine,

we want to smell the flowers

We’re sure that God has willed it,

And we mean to have eight hours”(1)

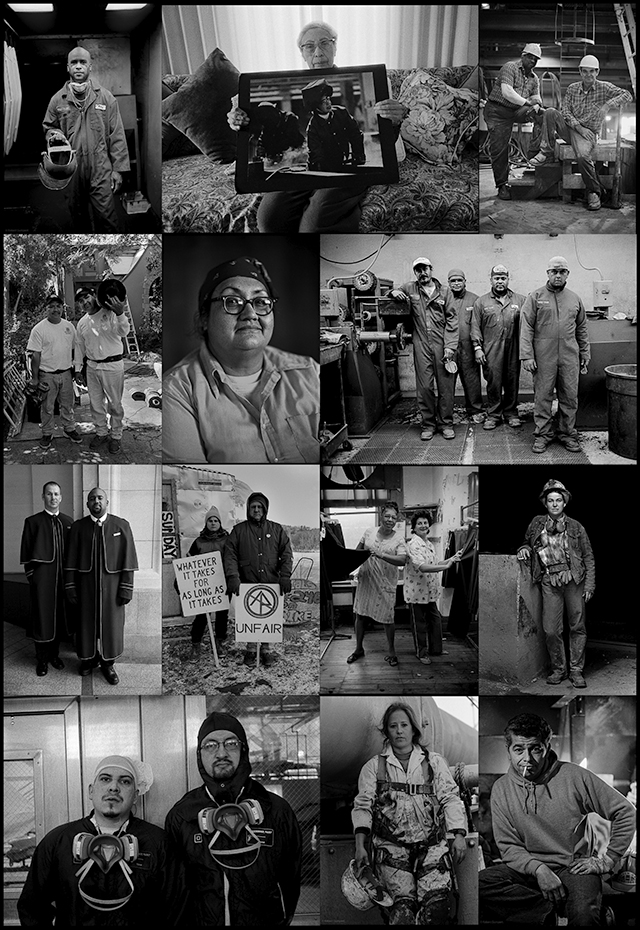

When we respect work and the people who do it, we respect ourselves and our brothers and sisters.

Another less anonymous poet, James Oppenheim wrote it thus in 1911:

“Small art and love and beauty their drudging spirits knew.

Yes, it is bread we fight for — but we fight for roses, too!

…No more the drudge and idler — ten that toil where one reposes,

But a sharing of life’s glories: Bread and roses! Bread and roses!”(2)

As we reflect on the dignity of labor and importance of decent conditions of work many of our own stories reflect the accomplishments of the generations before us. L’Dor V’Dor (or in English, “From Generation to Generation.”)

When I was a boy I would walk to the subway station near the Yankee Stadium to wait for my father to come home around seven pm and we would chat companionably for the three blocks to our apartment. Why seven: because the hours from 4-6:30 were overtime, time and a half: a “good” job for a garment cutter was one in which there was consistent overtime – that’s what made our first car – a Dodge – possible.

I should add that however secular my parents were, on Friday evening my Dad brought home flowers –and to this day so do my wife and I. Setting aside the Sabbath as a day where no work is done is the world’s first labor legislation.

So limiting worktime and rewarding it – is a part of the story of labor and Labor Day from Generation to Generation.

There was a time when there was a Jewish working class. Irving Howe notes that in New York forty percent of Jewish families had someone in the garment industry alone. But then, with Joni Mitchell and Judy Collins, they looked at love from both sides. My paternal grandfather was an organizer and leader in the early years of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. Comrade Borochowitz once said to my Dad, “the hardest thing to teach Jewish workers was that Jewish bosses were bosses.”

The Jewish working class was central to the building up of the institutions upon which 20th Century decency has rested. The garment workers invented the HMO; the men’s clothing workers were among the founders of the very first industrial union, members of the CIO and leaders in what we now call “social unionism”.

My mother was a New York schoolteacher. When we were young, she was a single mother. We were the working poor. Her marriage to my Dad relieved our penury, but when they grew older, the erosion of his union and industry meant that in his later work years he was in nonunion shops. The wages were ok – but there were no pension contributions.

But aha, in the intervening years New York City schoolteachers had won union recognition and negotiated good pensions. So in their later years my parents were all right. Remember Joe Biden’s great line about the plight of working families: Can you say, he asked, “honey, it’s going to be okay” Well, for so many of us the pressing question has been, Mom and Dad, “Will you be all right?” It was a blessing that mine were. That’s why I will never forgive those who tried to blame New York’s fiscal woes on my mother and her pension! L’Dor V’Dor.

As I reach the end of my academic career, I remember vividly its beginning. At the University of Chicago, we graduate students in Sociology felt the basis on which fellowships and assistantships were awarded was mysterious and we suspected a hint of favoritism. We were, simply, abject, powerless subjects. When we asked that the process become more transparent, we – I – became extremely unpopular with the senior faculty.

I have to laugh; graduate students at private universities have just won the right to be represented by unions.

Should they choose to protect themselves from whim and caprice there is now a means to do so. There are many lessons here, among them, amid looming threats: sometimes Good Things Do Happen! From generation to generation.

In the 1950s American workers achieved what centuries of alchemists and mystics could not: they turned the lead of working class status into the gold of middle class consumption. Or anyhow, that is what the mass media thinks. By “middle class” they mean household incomes that hover in a band around the 50% point, half above, half below. No matter that the half-way point is now way into insecurity, debt, and constant stress. In the Boston metro-area that is about $73,000. An MIT living wage calculator for a family of four is $78,000. How did that working class raise its standard of living, and how did they lose it?

In that era about one-third of the private sector labor force were union members or covered by union contracts; today that is around 7%, but there are higher rates among public sector workers, especially teachers. L’Dor V’Dor.

When Frances Perkins, a veteran of the progressive movement, Hull House and the longest serving Cabinet Secretary and Labor Secretary in history entered Roosevelt’s cabinet, labor issues were at the top of the agenda of her middle class allies. But only recently, through the “Fight for $15 and a union,” have folks re-imagined what is needed to insure decency. But our thinking still has blind spots.

Consider one of the criticisms of Bully Donald Trump’s declared child care “policy” (though I hesitate to grace it with such an elaborately worked word). He said childcare expenses should be deductible. Well, one voiced criticism was that poor people would not benefit because they don’t pay taxes anyhow. True enough and a criticism to note. But in the meantime, millions of families in the middle-income belt certainly do pay taxes and any way of gaining relief will be welcome. Working families need justice and social solidarity just as do poor people. From Generation to Generation.

When 146 women and men and girls and boys were killed in the Triangle Shirtwaist fire this was a searing event for Jews, for workers and for New Yorkers. And they and we have been ever mindful of our obligation of memory and solidarity. I am proud of the work done by the Jewish Labor Committee and the Massachusetts Interfaith Committee for Worker Justice and JALSA – the Jewish Alliance for Law and Social Action who have reached out to support the victims of the killing fires and collapses in Bangladesh and elsewhere.

Today our community is global — as is our understanding of our interests and values. Here is the way I think of it: Our grandparents and parents rose out of the sweatshops; we owe them our love and gratitude for their sacrifice and accomplishment. Around the world the workers of the rag trade still toil in those conditions. We owe them what we owe them.

Owning our time is to live free. After work, after rest, the Eight Hour song put it so succinctly; “Eight hours for what we will.” L’Dor V’Dor.

_______________________________________________________________

Footnotes:

1) Lyrics to Eight Hours

2) Lyrics to James Oppenheim’s “Bread and Roses”