The Fight for $15 and a Union – A movement in the making?

By Peter Olney and Rand Wilson

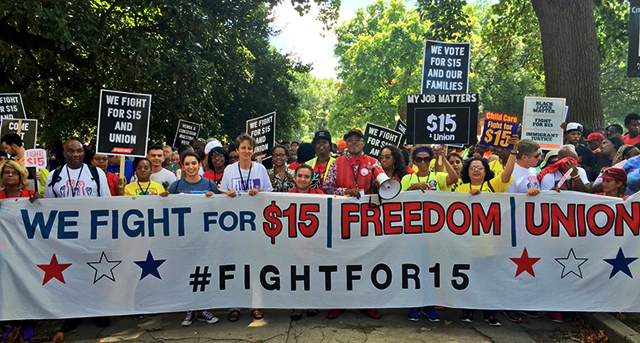

“Fight for $15” convention closed with a march on the Robert E. Lee monument that symbolizes racial supremacy. Photo: SEIU

After both the Republican and Democratic parties nominating conventions, there was a convention of a very different kind in Richmond Virginia on August 12 and 13. Thousands of low-wage workers and activists from all over the United States gathered for a Fight for $15 convention. The convention highlighted the links between the Fight for a $15 minimum hourly wage, economic equality and the struggle for racial justice. The selection of a venue in the capital of the Confederacy was no accident, and the convention closed on Saturday with a march on the Robert E. Lee monument that symbolizes racial supremacy.

This meeting was another movement-building step in the fight for a $15 per hour minimum wage. The Reverend William Barber, who only a few weeks before ignited the Democratic convention in Philadelphia with a blistering speech during prime time television, spoke at the closing rally and talked about the legacy of slavery and its connection to lingering poverty and other social problems.

The United States federal minimum wage was first established in 1938 at $.25 per hour. Over the years since, the minimum wage has been increased to $7.25 per hour, a totally inadequate living standard anywhere in the United States.

States (and some municipalities) are free to enact higher minimums, and states and cities with strong labor unions and progressive politics have done so. For example, the minimum wage in Massachusetts is now $10 and hour and in Michigan it is $8.50. The City of San Francisco has a $13 minimum wage. The states of the old Confederacy have the lowest minimums and have resisted grassroots efforts to raise them. Birmingham, Alabama recently raised its minimum to $10.10 but the raise was preempted by the Republican-dominated state legislature.

Both California and New York have recently raised their minimums to $15 per hour; phased in over 7 years to 2023 in California, and in greater New York City by 2021 and in the rest of the state in graduated fashion after 2021. While even these minimums are still a paltry income for struggling working class families, the change in minimums and the societal recognition of the need to drastically raise wages is a long overdue and welcome development.

The Service Employees International Union (SEIU) with almost 2 million members, mostly in the public sector, has been responsible for funding and leading the Fight for $15. Without its backing and national coordination, the one day strikes against McDonald’s and other fast food outlets would not have happened. One-day strikes began in 2012 and on August 29 of 2013 there were walkouts at fast food outlets in over 60 cities. The walkouts usually were by only a small percentage of the employees in each outlet, but members of SEIU and other unions along with community groups bolstered the strikes with large public rallies and demonstrations of support.

The actions were often characterized by observers as a “march on the media” rather than an actual march of the fast food workers themselves. Nevertheless, these actions generated a public “buzz” and put pressure on McDonald’s and the other fast food employers to raise wages. In early 2015 McDonalds’ announced that it would raise the company minimum for thousands of its employees.

the key to securing power for workers in this industry (as in other retail organizing) is building strategic power higher up in the industry’s supply chain

The Fight for $15 campaign has not yet been able to compel McDonald’s or any of the other fast food restaurants to recognize the union as the bargaining representative of its employees. It is often unclear how many workers actually remain involved in the day-to-day union organizing. Employee discipline and terminations in retaliation for supporting the union are rampant, and it is hard to defend discharged workers under U.S. labor law. Turnover in employment is high. Actual worker organization is thin. But the Fight for $15 driven by SEIU and supported by significant community-based forces has had a remarkable role in shifting consensus on US wage policy. No longer do the neo-classical supply side economists dominate the debate arguing that a rise in minimum wages will destroy jobs and the economy.

Historian and labor organizer Marty Bennett has pointed out that prior to the Fight for $15, there is a history of initiatives which have contributed to this sea change in public opinion:

• In 1996 the City of Baltimore, pressured by labor and community organizations, passed one of the first “Living Wage” ordinances mandating that businesses receiving city contracts pay more than the minimum wage. Los Angeles did the same in 1997.

• In 2011 “Occupy Wall Street” protests in cities throughout the U.S. targeted the growing economic disparity between the top 1% and the rest of the 99%.

• In 2012, the Fight for $15 and a union was launched with strikes at fast food outlets throughout the US.

• In 2013, SeaTac, a small city halfway between the cities of Seattle and Tacoma that encompasses the Seattle airport, passed a $15 minimum. In 2014 and 2015, San Francisco and Los Angeles followed suit.

• Bernie Sanders’ campaign for President explicitly called for a $15 federal minimum wage and pressured Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton to adopt $15 in the Democratic Party Platform.

As Fight for $15 advocates gathered in Richmond, Virginia for their convention, they celebrated the remarkable advances they have made in shaping the national dialogue; moving it away from austerity and to a focus on economic inequality. They also celebrated their part in a larger movement to significantly raise the minimum wage, impacting millions of low wage workers through state and municipal increases.

SEIU has made a remarkable commitment, putting enormous resources behind the fast food workers so they can pressure their employers for higher wages. But despite its short-term impact and success, the campaign has yet to build sustainable worker organization. Clearly the high turnover and the huge number of scattered franchised job sites make an enduring worker organization extremely difficult to maintain.

From the standpoint of union organizers committed to building strong worker-led, democratic unions, the key to securing power for workers in this industry (as in other retail organizing) is building strategic power higher up in the industry’s supply chain. The better off workers in company-owned and third-party warehouses and trucking companies who supply the goods to fast food outlets may make for more sustainable organizing even if they are far less glamorous. In turn, these “pinch points” in the supply chain are where key workers once organized can exert the strategic leverage to win organizing rights for the millions of workers who labor in the fast food restaurant industry.