Olney Odyssey #17 – Going Up – Adventures of an Elevator Operator

By Peter Olney

My brief tenure at NECCO in the fall of 1972 had gotten me more that an abrupt discharge for defacing company property with radical political slogans. In order to operate the freight elevator at the candy company in Central Square, Cambridge, I had become licensed in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to operate an elevator. A state inspector boarded my elevator, rode up and down with me, and scrutinized my ability to level the elevator by releasing the control knob just as the car approached the desired floor. Through a friend and comrade I found out that Boston City Hospital has an opening for an elevator operator. I had the license and I got the job in September of 1979. When I presented my self to work at the office of the elevator department, which was situated in the Housekeeping Department, I met my supervisors Peggy and John. Peggy had bright red hair and she staffed the office and took calls from angry hospital personnel looking for an elevator that was late in arriving and from operators who were calling in absent or late. John was the relief operator, and he was my trainer. He was very short; in fact he was a dwarf. I soon discovered that a prominent Harvard neurologist had decided in the 50’s that he wanted to study dwarfism. He needed his subjects to be near at hand for observation and so he prevailed upon BCH to hire dwarfs as elevator operators. I was therefore a hulking giant among my co-workers, at least the males, many of who were very short.

It was the one place in the city where Black, brown, Asian and white were patients and workers.

John trained me on the elevators in Dowling North and South. These were the two wings of the main surgical building at City Hospital. I spent most of my two years as an operator running these elevators. Occasionally I was stationed in pediatrics, the medical building or the laundry, but Dowling was where the action was. The emergency room was ground floor for Dowling. Boston’s knifings, gunshot wounds and catastrophic industrial accidents came to the Dowling for triage, and then if the patient was stabilized I transported them up to surgery or an ICU or recovery room. Dowling and BCH were Boston’s melting pot. It was the one place in the city where Black, brown, Asian and white were patients and workers.

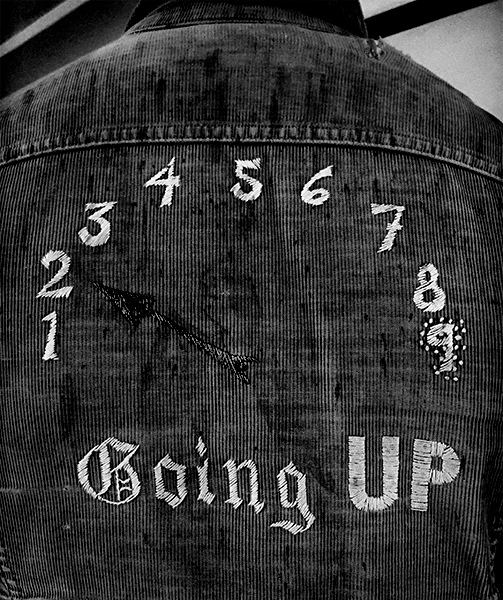

I greeted them all at the door of my elevator with a cheerful, “Going up” or “going down”. I carried visitors, patients and hospital staff. I would transport deceased patients down from surgery often accompanied by their family and visitors seeing their loved ones on other floors. There wasn’t much privacy at BCH. It was raw.

I transported the famous “Steve Martin arrow man” up to surgery. A laborer had been driving his utility truck in Southie one night after downing a few too many at the tavern, and he had run head first into a tree. His crow bar had come thru the window of his cab and gone straight through his head. He came into City and was brought onto my elevator on a gurney, but the paramedics had to tilt his head impaled by the crowbar in order to get through my elevator door. He went into surgery and the doctor, a Harvard trained African brain surgeon, successfully extracted the crow bar and saved the man’s life.

The job afforded me considerable flexibility because we were constantly being relieved to take breaks and lunch. In an eight-hour shift we probably were on duty a total of 4 hours. The job gave me a chance to do my studies as I had recently enrolled at U-Mass Boston to complete my college and learn Spanish. I could do my homework on breaks sitting in a secluded spot on an abandoned surgical floor. On weekends and evenings I could even read my Spanish literature while operating the elevator. That led to several interesting encounters. Young resident male surgeons had little interest in befriending or inquiring of the work force. They were blessed beings that had often grown up far from the grit of Boston’s working class. They would brusquely enter the elevator car and call out the floor they wanted often not even looking at the operator. They were however cognizant of the size and demeanor of most of my colleagues. Many of them as I mentioned were short and some had physical disabilities and missing limbs. One evening a young Harvard med-surgical resident entered my car. I was sitting on my stool reading Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes. This was the basic text for my introduction to Spanish literature. The surgeon scanned my limbs and looked at the text and made a quick decision that I must have some disability and because everything else looked in order he decided I was deaf. He promptly thrust 5 fingers in my face to signal that he wanted the fifth floor. Up we went. When we got to five I called out the floor and the Intensive Care Unit. He left befuddled.

I was not at the hospital to perfect my “altitudinal technician” skills or to bring good humor to the hospital community as a “vertical digital analyzer”. There is considerable lore about elevator operators being the spiritual lifeline for apartments buildings, manufacturing lofts and courthouses. The constant contact with people often in emotionally distraught or jubilant states, means that the operator is a force in people’s lives. I was at The City to organize workers. This workplace was already unionized in American Federation of State County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) Local 1489 for my job and those of the housekeepers and other blue-collar workers. The techs, ward clerks and nurses were all in the Service Employees International Union. Local 1489 was a colorful collection of people, the most diverse workforce in Boston. The President was a gay Italo-American security guard from Southie. The VP, a black nurses aid from Roxbury and the Recording Secretary a Chinese American woman from Michigan. I picked up the task of publishing the 1489 newsletter and made sure that it was translated into Spanish. I also became the steward for the elevator department and represented the grievances of my fellow operators. The City was tight knit community, and I spent a lot of time roaming the hospital at all hours and every day of the week. I remember returning to the hospital three years after I had left Boston for California. I was walking in one of the underground tunnels that linked the various buildings of the facility when I happened on an orderly who was pushing a gurney with a patient on it and a saline bag hanging hooked up to the patients’ arms. He abruptly stopped his gurney and said to me, “Where you been I have been looking for you for ages. I got a grievance I want you to handle!”

The elevator was a great organizing platform. I could transport groups of workers up to their designated areas and abruptly stop the elevator between floors and conduct a true captive audience meeting to review the issues of the day and encourage their participation in whatever activities the Local; was promoting. While I enjoyed the human contact, the union work and the flexibility I soon decided that I wasn’t cut out for a lifetime career as an operator. Plus it didn’t take a Marxist analysis to know that technology replace our department with automated lifts. I enrolled at the Northeast Institute of Industrial Technology on Beacon Hill. I was pursuing certification as a “frosty”, a refrigeration mechanic. This training would lead me to new adventures at The City and beyond top California.

Next: OO #18 – Minding the Morgue

Most interesting! Although I knew that you once operated elevators, I never knew the full story. I especially enjoyed the little side stories! By the way, I believe that those we once called “dwarfs” now prefer to be called “little people.” Francesca also got to know them as they formed at least part of the cleaners at her Federal Court House.