Advent – Another New Hampshire Runaway

By Peter Olney

…and the fact that the community and the workers were one and the same,…”

Soon after the Red Sox collapse in the fall of 1978, my employment at Advent ended. 18 of us were laid off in what was termed a seasonal production downturn. Rumors were swirling throughout the facility though that the company intended to move to the haven for runaways in New England, “Live Free or Die” New Hampshire. New Hampshire at that time was a conservative bastion and still is a right to work state with a very low percentage of unionized workers. It is a very different place from its western neighbor Vermont, a state with progressive traditions and a much higher union density, much of it because of the machine tool industry in the Connecticut River valley that was heavily organized by the union I was in at Mass Machine, the left- wing United Electrical, Radio and Machine workers, the UE (as we have linked before to the UE, here is an oral history of Ernest DeMaio, head of the United Electrical Workers Midwest District 11).

Talk inside Advent was that the company was already building a new factory in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. I have learned that such rumors are always worth tracking down. Barbara, a comrade and sister organizer had also been laid off. Instead of doing a “Google” search we climbed in a car and set out for Portsmouth exactly 56 miles away. We drove around likely sites where construction was going on and found a huge clearing, the Portsmouth Industrial Park, on Heritage Road off Route 1. I barged into the construction trailer and inspected the floor plans on the draftsman table. There was also an artist’s drawing of what the new building would look like. The workers told us that the building had been under construction for 1 1/2 to 2 months. The concrete foundation had been poured. Yes indeed, Advent was coming to New Hampshire. Nowadays I would have taken a snapshot of the foundation and the floor plan with my “smartphone”, but in 1978 our word would suffice. We had the company red-handed. We knew the number of the real estate parcels and the name of the real estate developer. We were ready to blow the whistle on Advent’s plans to steal away with no notice to the workforce.

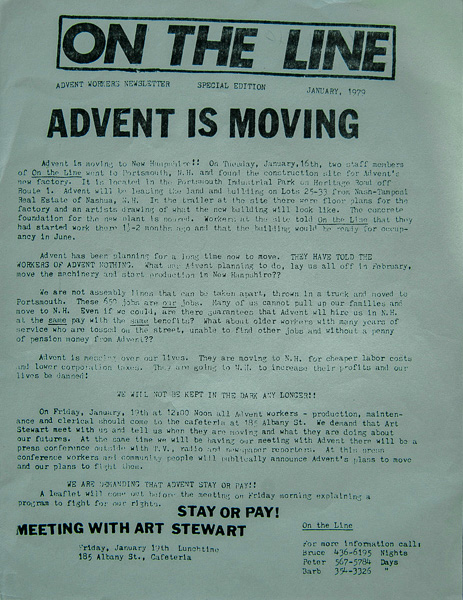

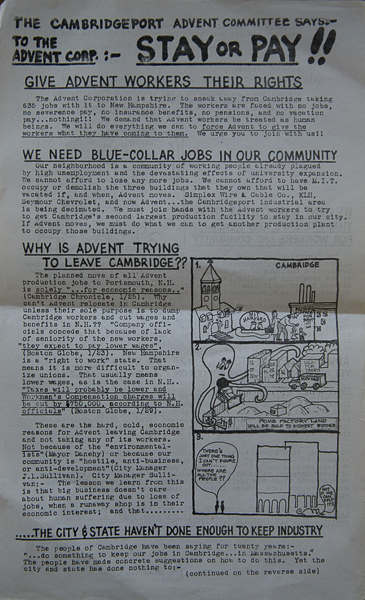

We rushed back to Cambridge and roughed out a flyer to be distributed the next morning at the gates of Advent. Copies were made with the most current technology, a mimeograph machine with an electronically etched stencil! Nowadays a twitter message and Facebook would probably bring the bad tidings to the workforce. The flyer was entitled, “Advent is Moving” and it lambasted the company: “Advent has been planning for a long time to move. THEY HAVE TOLD THE WORKERS OF ADVENT NOTHING. What was Advent planning to do, lay us all off in February, move the machinery and start production in New Hampshire??” At the bottom of the flyer was the slogan “Stay or Pay” and a call for a meeting with Art Stewart, the plant manager in the cafeteria at noontime on Friday, January 19th.

Friday came quickly. The cafeteria was full of almost all 600 employees. We made sure that some of the members of the Cambridgeport Advent Committee were in the room. They had long protested the toxic emissions from the Emily Street facility and had forced the company to install expensive air quality filters. The buzz briefly subsided into a hush when Peter Sprague, the cavalier capitalist owner mounted a table to address the workers. He could not have foreseen the audacity of the majority immigrant workforce and certainly he did not expect that Comrade Bruce would mount the table opposite him to go point counter point with him. Sprague charged through the Advent talking points: the need for a modern single story facility, the desire for a less hostile community and the overly regulated business environment in Massachusetts. Bruce was able to point to the greed that was driving the move, and the fact that the community and the workers were one and the same, endangered by toxic substances on the line or in their neighborhoods. But fundamentally what carried the day was the fact that Sprague never had any intention of telling the workers before hand about the decision to shut down. In an interview later with the Boston Phoenix Sprague said, “We didn’t tell them before now because we needed the production, and we figured they might walk out. And they would have been out of work anyway – so what difference does it make?”

Raw anger at Sprague’s hubris overrode any of the corporate competitive arguments.

As Bruce agitated the workforce, the climate became more heated and Sprague dismounted from the cafeteria table and left with Art Stewart to the jeers of the Advent workers. Sprague had no plans to meet with the workers again. In official written communications the company was holding out the promise of a modest severance package as a condition of the workers finishing work and staying on until February 15th, the last day of production.

The fight against the runaway began on several fronts, legal charges and a mass protest at the “golden dome”, the historic Massachusetts State House on Beacon Street. The question needs to be asked why red hots like us were not pushing a factory occupation strategy? I guess in our new deference to the “mass line” we thought that the workers would not take such action because of the fear of losing the proposed severance package, but in retrospect, as with Mass Machine the occupation strategy was probably a very plausible route and something that might have appealed to the temperament and experience of some of the workers. In our urgency to discard the left sloganeering and idealist socialist appeals and root ourselves in the day to day struggles we had lost sight of the fact that often a spark of imagination and daring is just what folks need to rise up and defend their interests. That can be the role of leadership, not getting way out ahead of folks but always testing the waters and respectfully pushing the envelope. Probably an opportunity lost to capture the imagination and support of the public that was aggrieved with the beginnings of a new wave of capital flight.

Instead on Friday, January 26, in the dead of winter we organized a bus caravan to the State House, leaving after work. The City of Cambridge authorized the expense of renting the school buses. Every press and TV outlet in the greater Boston area was present. Politicians joined our rally and then we were given a meeting with Governor King’s Secretary of Economic Affairs, George Kariotis. Ed King had been the Chairman of the Massachusetts Port Authority – Mass Port and was seen as a business friendly candidate who would restore the economy after the term of the pointy headed liberal Michael Dukakis who he beat in the Democratic gubernatorial primary.

When confronted with the demand to Stay or Pay, Kariotis responded that, “We cannot force him to pay you severance pay; we cannot force him to build a plant on a vacant lot anywhere else. We have no legal means to force a company to do these things…” Furthermore Kariotis stated that he wouldn’t want to have that kind of power because it would scare potential businesses away from the state. After the Kariotis meeting Bruce addressed the workers outside in bitter cold near the monument to the Massachusetts 54th regiment, an all black unit that fought in the Civil War. Fleischer said, “The struggle will continue. It is clear that we have no friends here.” Certainly in speaking of Governor King, he was right, but several state legislators had joined our rally and Saundra Graham, the African American state representative from Cambridge was all over our struggle offering support and encouragement at every turn.

The father daughter attorney team of Harold and Robin Kowal filed a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) charge arguing that the move to New Hampshire was in response to the workers organizing. This was an extremely plausible theory that was well documented in their brief to the Board. They asked for injunctive relief to stop the movement of plant and equipment to Portsmouth so that in the event our charges were found to be bona fide and the remedy was “status quo ante”, the company would not already be in New Hampshire. Ironically the company was defended by the same law firm that had defended Mass Machine, Tepper and Berlin, and the wily old silver fox, Alan Tepper, again prevailed and the charges were dismissed.

We are representatives of the face of the troubled working class…”

With prospects dim for any rescue of the jobs and any commitment to hire displaced Cambridge workers in New Hampshire, it was time to celebrate each other and our community and persevere in fighting for the best severance package and Trade Readjustment Act (here and here) monies. TRA subsidized unemployment benefits up to 70% of normal wages for a period of 52 weeks in the event of loss of employment due to the impact of foreign competition. There were no clear measures of foreign competition, but there were certainly clear measures on the decibel meter of loud protest. Advent workers were in the news and raising their voices, they were the squeaky wheel that got the TRA regardless of any objective analysis of the reasons for the job loss. In fact the authorization for TRA for the loudspeaker workers came on February 15, the same day as the shutdown.

On Saturday night, February 10, 100 workers gathered at the Black Elks Club in Cambridge for a final hurrah before the shutdown. The theme of the party was “Saturday Night Proud of Our Fight” Every nationality was represented and Marco Castro summed it up for all when he said, “We are representatives of the face of the troubled working class. We are in trouble right now and would like to be helped, because tomorrow I’m going to go to work for another company for five years and that company may runaway too.” Nevertheless there was a certain pleasure in the achievements of the workers as the final edition of On the Line pointed out, “All of us will remember when we sent Sprague, Ed ‘Bulldog” Cobb and Art Stewart running from our cafeteria meeting. We are proud of our fight and will carry its lessons with us wherever we work in the future.”

Even after the shut down Advent workers remained in the public eye and appeared at a State House Senate Commerce and Labor Committee hearing on plant closure legislation that would give workers 1 year advance notice of closure, minimum severance of one week’s pay for each year of service and a 15% of one year’s company payroll as a contribution into a community assistance fund to be tapped for workers in the case of a runaway or shutdown. The bill never became law but it was a harbinger of future legislative fights in Massachusetts and later for me in California in the early 80’s when the wave of shutdowns and relocations would shock the industrial working class.

Next Olney Odyssey #16 – Sintered Metals Inc., Softball and the fall of Somoza

As it happens, questions that were emerging in my mind got answered by the end: namely, (a) was there any law-federal or otherwise–that made it illegal to pick up a factory and relocate to anther state?; and (b) had you occupied the factory there at the end and forfeited the promised severance pay, was there any law requiring a private company to pay severance pay. If I understood you, there were no such laws at that time. But I do have a question: did any Cambridge workers take jobs in the NH plant? And while I’m at it: Did Advent survive to this day there in NH?

15 September 2015: Peter Onley replies: If the Advent workers had occupied the factory there was no law that guaranteed them severance. I do not believe that any production workers went to Portsmouth although I stand to be corrected. Advent Corporation no longer exists.