00#7 Making NECCO Wafers – Fall 1972

By Peter Olney

“All-day suckers and lolly pops

Maple fudges and chocolate drops!

Wares that satisfy; goods that please!

Who sells lovelier things than these?

Who among all of our working clan

Has a happier trade than the candy man?”The Candy Man by Edgar Guest

I arrived back in the USA in late August of 1972 deplaning at JFK in New York City where I had started my Italian adventure the previous year. I had one small bag, and stuck my thumb out and hitched to Boston. I checked in with my parents in Andover and then headed for The Hub and my friends from the Lewd Moose commune of the summer of ‘71. Two of them, Buck and Steve had bought a house on Pine Street in the same Central Square neighborhood where we had lived together. I was invited to stay, along with half of the street lumpen kids from East Cambridge. My bedroom was in a dank basement that would flood occasionally and I would wake up and stick out my hand for a depth reading before trying to climb out of bed.

Steve and Buck, being movement entrepreneurs, had the idea that they could fund the movement by raising money with events featuring progressive rock stars and cultural icons. The initiative was called “Entropy” and they became mildly successful promoters. One day I remember being told not to barge in on the master bedroom because Allen Ginsburg was using it for some pre performance meditation. There sat the rotund rollypolly Ginsburg oohming in the upstairs bedroom. I think I was the only one in the house with a regular job, which conveniently was a stone’s throw up on Massachusetts Avenue at Albany Street at the New England Confectionery Company (NECCO). NECCO is famous for NECCO wafers and for the Whitman Sampler chocolate assortment box gifted on Valentine’s and Mother’s Day.

My decision to work at NECOO was not the product of deep scientific analysis. I needed a job to support my self, and my Italian experience inspired me to want to be a part of the US working class. I thought that any radical change in America would come from building a strong workers movement, like the one I had seen in Italy.

Like so many other workers in my experience they referenced the good old days when working at NECCO was like being part of a family.

My job at NECCO was to start work early at 5 AM, just when the frequent all night party was winding down at 51 Pine Street. I was the freight elevator operator, and I received a license from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to operate. My job was to carry raw materials and workers, mostly older ethnic Italian, Portuguese and Irish ladies up to the production floors. I enjoyed practicing my Italian with the ladies who mostly spoke Sicilian and Neapolitan dialects. I soon became attuned to some of their issues in the workplace. The clanging noise of “Rolo” and “Skybar” molds being hammered to release the product drove the noise decibel levels over 90, unsafe for human ears. The cold storage area for the filberts and peanuts used in the chocolates was infested with rats. There was a human element to the pestilence also that tamed any desire for milk chocolate on my part. Manny, an older Portuguese worker from the Azores loved to stand in front of all the other male workers in the early AM, and relieve himself into the chocolate vats. I started to talk issues with the women as we rode the elevator, and of course I had a captive audience because I could stop between floors and hold forth with my opinions about their working lives. Like so many other workers in my experience they referenced the good old days when working at NECCO was like being part of a family. Change started to happen in 1962 when NECCO was purchased by the United Industrial Syndicate (UIS) out of New York. UIS was a publicly traded conglomerate that was in the business of picking up manufacturing companies and squeezing their assets for super profits. The women were victims of that drive for increased profitability. The plant manager, Tom Antonellis, a former Boston College football star, would come down on the assembly line and fill up the line with Whitman Sampler boxes so that the ladies had to work even faster during the holiday season.

My employment at NECCO was short lived because of a classic moment of youthful idealism. The Vietnam War continued to rage, and I continued to have my strong feelings about US imperialism. At one point I came to work early and scrawled “Victory to the NLF’ on the elevator walls. I am not sure that Victory to the National Liberation Front, the Viet Cong, was an educational and teachable moment for my elevator passengers most of who didn’t speak or read English let alone know who the NLF was. But there it was penned in magic marker on the wall. It did catch the attention of management, and I was summoned to the Personnel Director’s office. The director was an old blue-blooded Bostonian who probably was given the job as a life cushion after graduating from Harvard. He wore a natty bow tie and proceeded to lecture me calmly about the offense I had committed, defacing company property. He said however, “I understand people have strong feelings about these issues, and if you will promise not to do it again you can keep your job.” I immediately expressed my strong feelings, “Absolutely, I will NOT promise never to do it again”, and I swiftly exited the chocolate factory in December of 1972.

I arrived early and was chatting with some of the Italian ladies when two giants in leisure suits from the BCT approached me.

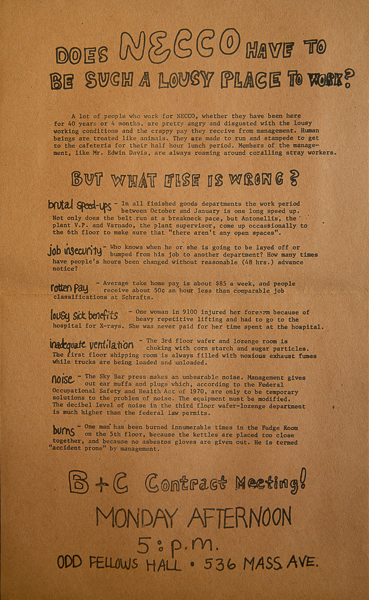

Even though I was on the street my involvement with NECCO and its workforce was not over. I had earlier connected with an organization called Urban Planning Aid (UPA), headquartered in Central Square. This was a movement consortium specializing in technical expertise in communication, health and safety and other organizing skills. I was particularly interested in health and safety issues given some of the deplorable conditions at NECCO. The labor contract was expiring at the end of January, 1973 for the workers. They were in union Local 348 of the Bakery Confectionery and Tobacco Workers Union (BCT). I decided with the help of UPA to do some street agitation about the health and safety conditions hoping that the union would be spurred to address them with the company. I call it “street” agitation because I was out on the street handing out flyers calling out the noise and the rats in the peanut bags. I got a nice welcome from my ex-elevator passengers who appreciated seeing me in the biting winter cold handing out the newsletter. The BCT was not so hospitable.

I went to the first union meeting of my life on January 22, 1973. The meeting was scheduled in order to update the members on the BCT contract negotiations with NECCO. It was on the second floor of the Odd Fellows Hall at 536 Massachusetts Avenue in Central Square. I arrived early and was chatting with some of the Italian ladies when two giants in leisure suits from the BCT approached me. I was no small lithesome guy, and still they proceeded to pick me up in a fireman’s carry, dragged me down the stairs and deposited me outside on Mass Ave. The contract was ratified and didn’t deal with any of the issues I was agitating about. I have learned that health and safety issues are often of utmost importance to workers, because while pay and benefits are fundamental, the breaking point that often spurs action are issues of human dignity that involve life and limb and safety and health. That was true at NECCO and has been true in every workplace I have organized since.

Of course in retrospect I might have been more effective at NECCO if I had told Mr. Blue Blood, the Personnel Director, that I would promise of course never to deface company property. Then there would have been no legitimate basis for the BCT goons to throw me out of the meeting and I would have had the daily ear of the workers on my elevator. But those were times of high idealism and little political seasoning. I chose principle over pragmatism and who paid the price?

Writing in my journal on December 22 I characterized my decision as “Stupid honesty” and reflected that I had let “Pride and a moral code that you have rejected intellectually, determine the decision”

Next – OO#8: Mass Machine Shop and the United Electrical Workers (UE)

Lillian R. Rubin – On Tuesday, June 17, my friend Lillian R. Rubin died. She was 90 years old. I was scheduled to have lunch with her on Friday, June 20 at Garibaldi’s restaurant on Presidio in San Francisco. I would arrive there for my monthly luncheon with her and ask for Dr. Rubin. The maître de would usher me to her favorite table at a corner spot in the back of the restaurant. Lillian was a sociologist, psychotherapist and doctor in psychology from Berkeley and an accomplished writer and commentator on matters of class, race and family in America. I had read her most famous book, Worlds of Pain: Life in the Working Class Family, as a young organizer in Boston almost 40 years ago so I was thrilled to meet her through a mutual friend in SF. Lillian was a woman who led an extraordinary life, and I will leave it to others who knew her longer and better to tell her story.

Here is her daughter Marci’s tribute and here is the obituary published in the New York Times

Lillian was a writer/mentor constantly challenging me to begin each essay with a paragraph telling the reader what I was going to write about. She would admonish me to go deeper and stop with the bland “encomiums”. I will miss her sharp edits of my essays. I hope that I have improved a little bit because of her coaching. She is missed in my life.

John Bowman picked up on something that several others have commented on. In OO #7 I made a passing reference to a worker peeing in the chocolate vats at the NECCO candy factory. He asks why was there no outrage and subsequent action taken about this issue of public health and safety.

I have found that it is very common for those of us who entered the working class from the outside to tell “war” stories about some of the outrageous things that our fellow workers did to deal with their deep alienation from their work In retrospect it might have been an issue to be dealt with and organized around. After all what about the poor consumer who was buying their Whitman Sampler expecting certain standards of cleanliness?!

I suspect that I am not the only devoted reader of Peter’s account of his time at NECCO to be taken aback by the casual mention of a worker pissing into the vat of chocolate. Peter went to some lengths to step back and admit that posting that graffiti about the Vietnamese NLF was probably an instance of youthful indiscretion–“stupid honesty” he calls it. But he makes no comment on that worker’s action–which I am willing to believe he really would not condone. To my way of thinking,, being even an ardent pro-labor advocate doesn’t include accepting such conduct.