Pete Hegseth — Offense at the Defense Department

By Tom Gallagher

“Trump slams Biden, praises ‘tough cookie’ Hegseth …” Politico 26 May 2025

Isn’t the most remarkable — and least remarked-upon — aspect of the Pete Hegseth Defense Department reality show the fact that no one has appeared worried that the nation’s security might actually be threatened by this? That no one has seemed particularly concerned about any danger resulting from the vast U.S. military arsenal ostensibly being placed in the hands of someone who had obviously not read the job manual? But then why would they? Did anyone seriously think China’s Ministry of State Security was dashing off memos advising the country’s leaders to invade the United States because control of its armed forces had somehow fallen into inept hands? Or that something like that was going on in Russia … or Denmark … or Canada … or any other of our enemies, old or new?

Apparently not. Why? Well, at recent count, the U.S. was in possession of a fleet of 299 deployable combat vessels; 3,748 nuclear warheads; 5,500 military aircraft; 13,000 drones; and 2,079,142 military personnel. All of this comes with highly detailed operational plans for situations involving an actual attack on the nation. But no one seemed to think that what Hegseth was spending his time on had much, if anything, to do with that eventuality. From the point of view of the nation’s legitimate security, that’s a good thing. But it raises the question of what was Hegseth on about, anyhow?

The story that brought the question of the Trump foreign policy team’s competence to the fore has little to do with the matter of American national defense. What it’s really about is the unauthorized, global use of American military force. The few Americans whose well-being was plausibly threatened by Hegseth’s now infamous sharing of the details of upcoming bombing missions — with his wife, brother, lawyer, as well as the editor of The Atlantic — were the pilots of those missions.

The object of this now haulted bombing campaign — which the Administration says has struck a thousand targets — is the Yemen rebel group called the Houthis, an organization allied with Iran and militarily opposed by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The recent U.S. attacks came in response to a resumption of Houthi efforts to block Israeli shipping in the Arabian Gulf that followed upon Israel’s breaking of its ceasefire agreement with Hamas, along with its blocking of humanitarian aid to Gaza. In response to the renewed U.S. assault, the Houthis attacked the U.S.S. Harry S. Truman, the aircraft carrier which then-President Biden deployed to the Gulf last December as a base for the anti-Houthi airstrikes that he had ordered.

Now, although it may seem quaint to mention such technicalities as the law in relation to the routine U.S. bombing of another nation, the truth of the matter is that — whether one considers bombing the Houthis to free up Arabian Gulf shipping a good idea, or whether one doesn’t — we are simply not at war either with the government of Yemen or with the Houthis trying to supplant it. Nor has Congress authorized the use of force there, in lieu of a declaration of war.

If you have trouble recalling Congress declaring war, that’s because you probably weren’t alive in 1942, the last time it did so (against Bulgaria, Hungary and Rumania.) The wars in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan? No declaration of war deemed necessary. And while the current Republican-controlled Congress may be distinguishing itself for new depths of subservience, generally the Democrat and Republican leadership alike tend to act as if questions of war and peace were above their pay grade, with only a minority of Democrats and a handful of Republicans ever making noise about the latest military action taken in our name. Congress’s ultimate responsibility notwithstanding, Presidents Biden and Trump have made their decisions to launch attacks on Yemen unilaterally.

What we’re dealing with here is what we might call the Defense Department’s Offense Division — the part that maintains the 700–800 foreign military bases around the globe (the exact number is classified, but maybe if you could get your number on Hegseth’s phone list …), along with the ships that ply its waters and the planes and drones that fly its airs. As previously noted, Trump is not the first President to bomb Yemen. And while, as in so many areas, he may well be the crudest exponent and practitioner of American foreign policy that we’ve seen in some time, the bombs Trump orders do not fall far from those dropped by previous administrations. Prior to the current episode, the U.S. has bombed Yemen during every single year since 2009 — nearly three hundred times, primarily via drone.

Nor is Yemen the first country bombed during the second Trump Administration; Iraq, Syria and Somalia have preceded it. None of this was considered much by way of news — a failing of the news media, yes — but less so than of the congressional leaders who have failed to make it news. Here too, while Trump may denigrate his predecessors, he apparently takes no issue with their bombing choices, joining the George W. Bush, Obama, Trump I, and Biden Administrations in the serial bombing of Somalia that has occurred more than 350 times over the course of those presidencies. The U.S. has also bombed Syria and Iraq every year since 2014.

All of this has been justified under tortured, expansive legal interpretations of the 2001 and 2002 Authorizations for Use of Military Force permitting military action against entities that “planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons” as well as “to defend the national security of the United States against the continuing threat posed by Iraq.” Under Bush, the authorization was interpreted to extend to the occupation of Iraq. Under Obama, it would encompass action against groups that did not even exist in 2001, but were “descendants” or “successors” — such as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). The first Trump Administration would expand that logic to warfare against eight different groups — including the assassination of an Iranian military commander. It was now understood to allow for military actions anywhere on the globe.

Before the Trumpists coopted the use of the term “Deep State” to encompass what they believe to be a malign government network that supports programs like Social Security, or Medicare, the term was used by quite a different group of people to quite a different end. The Deep State back then referred to the unelected elements of the government committed to waging endless war, often covert, often illegal — e.g. the Central Intelligence Agency — the sort of thing President Lyndon Johnson was talking about when he said that under President Kennedy the U.S. had been running “a damned Murder, Inc. in the Caribbean.”

We don’t call that the Deep State anymore because, as the above discussion indicates, our government no longer feels a need to hide these things. It’s above ground now — part of the DoD’s Offense Division. The CIA now conducts assassinations openly — via drone.

This is the part of the U.S. Government that should really worry us. It’s what Pete Hegseth was hired to run, something that was clear right from his Senate confirmation hearings that culminated in a narrower win than even his boss’s on Election Day — his approval requiring a Vice Presidential tie-breaking vote for only the second time in history (the first being the approval of Betsy DeVos as Trump I Secretary of Education). From the get go, Hegseth was forthright in declaring himself against increased “wokeness” — and for increased “lethality.”

One simple way to increase lethality is to broaden the potential killing range. And in this area, Hegseth came with a pretty strong record, having successfully lobbied for pardons of soldiers convicted of war crimes during the first Trump Administration, and suggesting in a book he wrote last year,“The War on Warriors,” that rather than adhering to the Geneva conventions, the U.S. would be “better off in winning our wars according to our own rules.”

Nor has he missed a beat since taking office; he’s announced plans to terminate the Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response office and the Civilian Protection Center of Excellence, and the Army will no longer require training in the law of war; henceforth it will be optional. Results have quickly followed, with the bombing of a migrant detention center in Yemen, for instance. One of Hegseth’s infamous Signal chats even described the targeting of a civilian location.

One last thought for the Secretary: Pete, If you were to spend your time on our national defense — instead of “lethality” in attacking foreign nations with which we are not at war — you could probably rest easier about using your phone. Of course, we both know that’d get you fired in a New York minute. You’re there to play offense.

…

We will never ever accept to be ignored and be treated as worthless

By Ibrahim Diallo

Peter Olney:

Lyft and Uber are in talks with the Labor Commissioner, the State Attorney General, and the city attorneys from Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Diego over the massive wage theft they inflicted on drivers after the passage of Assembly Bill 5 which classified them as employees. At stake is tens of billions of dollars in stolen wages and unpaid expenses from years of misclassification. On May 21st, the parties were scheduled to meet to discuss the future of the case, and on May 20th they heard from drivers statewide at rallies organized by Rideshare Drivers United (RDU) . Rallies were held in San Francisco, Los Angeles and San Diego.

At the rally at San Francisco City Hall, Ibrahim Diallo, a driver who was deactivated by Uber in 2023 gave a stirring address.

Ibrahim Diallo: My speech for our Wages Claim

There is absolutely no place on earth where people’s freedom or rights were given free. People always need to constantly fight with a big determination to never give up, to obtain it.

Please never forget that there will be no exception for us Rideshare Drivers United. So, we must stand up for ourselves, as no one will do it for us

We Drivers also play a very important role in our current world.

Let’s remind people who we are because many tend to either forget, underestimate or maybe even neglect how crucial and preponderant our position is.

We will never ever accept to be ignored and be treated as worthless.

In the preamble of the Declaration of independence of the United States it says:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

That is all we are asking for. Our “pursuit of happiness” is not respected and guaranteed.

Who are we?

We are part of the backbone of our society, which we can hardly imagine without transportation services.

We are those guys of all genders, colors, and faiths, young and old who are dedicated to serving you, 24 hours a day without any discrimination.

We are the dawn breakers who safely drop you at work, school, hospital and at your other errands and back home.

We are the ones who avoid you to miss your trains and planes (flights).

We are the night owls who still tolerate and accept to come back on the road to serve you, even after drunk clients often vomit or use our cars as a restroom.

Sometimes Uber refuses to pay for our cleaning fees.

Like this bartender/girl once told me with a big humor, on a late Friday night in Seattle: “You bring them (clients) to us sober, we get them drunk for you to come and safely drop them home. Then lastly you come and safely drop us (bartenders) home, before you go sleep”.

We are those who are exposed to all kind of crazy situations, like a client intentionally broke my right mirror and Uber decline to fix it. I had to fix it from my own pocket, otherwise my car is not fit to drive for them.

We are the ones braving all types of weathers: rain, fog, wind, cold to go out and serve you.

We are the braves risking their lives, who could be victims of drunk drivers on the road.

One day of strike of all taxi and Uber/Lyft drivers would paralyze all the country and have an impact on all sectors of our economy.

How can you dare to marginalize us?

We are doing the same type of job as taxi, limousine and bus drivers who are obviously well regulated and have much better treatment.

How can you not consider us as them?

Are we less human?

How the hell can you not make sure we have a better treatment?

Are you receiving some cut from Uber and Lyft?

How can California and the Federal Government not guarantee equal dignity to both Uber&Lyft drivers?

How can you close your eyes and ignore the crime which has been happening for so long in your state, your country?

When we see or know about an injustice, and we can do something to prevent or stop it, but don’t do anything, then we are crystal clearly complicit.

Consequently, if California government does not definitely eradicate this 21st century slavery (which is a kind of sharecropping), we Uber/Lyft drivers hold them complicit and responsible, as they are the guarantor of justice for their citizens’ welfare — “we hold these truths to be self-evident…our pursuit of happiness…” which is in the preamble of the Declaration of Independence of the United States.

Uber said they were losing money, which is why they could not raise drivers’ income and pay their shareholders. Yet they paid about $200 million to their lawyers to lobby to reverse PROP 22.

How do you dare to underpay and exploit us?

If Uber and Lyft clients, even non clients, knew what could be the negative impacts of the bad treatments we are undergoing, everyone would join on the street to come and fight for us to have more safety.

What are the risks to which people can be exposed with the current situation?

Do you want to ride with a stressed, depressed, tired, and sleepy driver?

Do you want to ride with a hungry and angry driver?

Certainly no.

But FYI, many drivers are, because they are obliged to drive 10 to 12 hours per shift for 6, or even 7 days a week to meet the ends.

Remember also, that when Uber drivers are affected their families and dear ones are as well. So too schools, and other work places because “WE ALL ARE ONE”.

…

Lessons of Labor for Bernie

By Steve Early

Challenging and Changing Union Decisions About Politics Takes Rank-And-File Action

The experience of seeing fellow union members fall for the faux populism of Donald Trump in 2024 has led to much soul-searching about why working-class people vote for billionaire-backed candidates—or don’t vote at all.

In 2016 and 2020, unlike last year, labor voters had a chance to rally around a candidate for the presidency who campaigned against the “billionaire class” (and is still doing so as part of his current “Fighting the Oligarchy” tour).

Within organized labor, a grassroots network of union activists strongly supported Bernie Sanders’ two bids for the White House. Campaigning under the banner of “Labor for Bernie” (L4B), they helped shape rank-and-file opinion for the better, put pressure on the national AFL-CIO and its affiliates to make political endorsements more democratically, and, in Democratic presidential primaries, helped boost turn-out for a candidate actually worthy of the union label.

Rank-and-filers trying to make their voices heard, in such oppositional fashion in the future, will face similar difficulty challenging and changing leadership decisions about what politicians to back or not.

Those hoping to launch more labor-backed independent candidacies, outside a corporate-dominated Democratic Party, will get even more push-back from the AFL-CIO and its affiliates—if their past levels of support for Sanders are any guide.

Yet the political and economic upheavals triggered by Trump’s second presidency will inevitably create cross-union insurgencies and internal union ones, leading, in some cases, to greater receptiveness to the idea of doing politics differently. That’s why the lessons of two rounds of L4B campaigning, as recalled below, remain timely and relevant at the moment.

Labor for Bernie, 2016

Bernie Sanders’ announcement in March, 2015 that he was running for president was initially regarded by supporters of Hillary Rodham Clinton as just a minor irritant. Corporate Democrats viewed the then U.S. Senator, former Congressman, and ex-mayor of Burlington, Vt. with particular resentment as a party crasher.

For the previous 45 years, he had been a frequent critic of both major parties. He also proudly maintained his ballot line brand as an “Independent,” rather than become a Democrat (while he caucused with them in the House and Senate). Most Clintonites viewed the anti-war socialist as a marginal protest candidate of the Dennis Kucinich sort, who wouldn’t win a single state primary (other than possibly Vermont’s).

Unfortunately for Clinton and a national AFL-CIO eager to endorse her, Sanders started out with a few more out-of-state friends than they realized—and quickly attracted hundreds of thousands more. Among them were union activists in the northeast with much past personal experience working with Bernie on key labor causes, locally, regionally, and nationally. Sanders’ working-class orientation, political independence, and rejection of corporate money was a major selling point for them, not a personal liability.

As Don Trementozzi, leader of a Communications Workers of America (CWA) local based in New Hampshire, pointed out: “Bernie was not on the fence or the wrong side, like Hillary Clinton, when our union was campaigning against the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP). He was helping us lead the fight against that job killing free trade deal back by Democrats and Republicans alike.”

John Murphy, a Carpenters Local 40 steward in Lowell, Mass., favored Sanders because of his “long record of supporting workers and their right to unionize.” When some fellow building trades members questioned whether Bernie could win, Murphy told them: “That’s up to us!”

On June 25, 2015, Trementozzi and Murphy joined 1,000 other local union elected officers, shop stewards, organizers and rank-and-file members from 50 states and 57 different unions who kicked off “Labor for Bernie 2016.”

They urged their respective national unions and the AL-CIO to get behind the only presidential candidate “who challenges the billionaires who are trying to steal our pensions, our jobs, our homes, and what’s left of our democracy.”

In a letter sent the same day to then AFL-CIO President Rich Trumka, Labor for Bernie (L4B) supporters strongly objected to any “premature endorsement” made without “the broadest possible membership participation in the electoral process.”

Instead, they urged the labor federation and its affiliates to sponsor grassroots candidate forums and debates, throughout the primary season, and forego making any presidential pick until the 2016 primaries were over.

Not Feeling the Bern?

This was definitely not the preferred time-table of the Clinton campaign or top union officials. So Trumka, John Podesta, Clinton’s Campaign Manager, and Nikki Budzinski, her Labor Outreach Director, began conferring about how to overcome any delay in the AFL-CIO executive council’s endorsement of Clinton by the required 2/3 vote.

One such conversation with Trumka on this matter was held four months after L4B was launched. As WikiLeaks later disclosed, the AFL-CIO president, in Podesta’s words, was very “keen on convincing union members that they could trust HRC to fight for them.” According to Trumka, as recounted by Podesta, few unions were “feeling the Bern,” “only APWU was likely to endorse him” and, if “pushed hard,” Larry Hanley, then president of the Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) “might end up endorsing HRC.”

Podesta informed fellow Clinton campaign staffers that Trumka “didn’t think CWA was likely to go with Bernie” either and that “Larry Cohen [its recently retired national president] wasn’t playing that well at his surrogate appearances” in front of other labor audiences.

At the time of this exchange, CWA was–as recommended by the AFL-CIO itself—in the middle of a three-month process of membership meetings, telephone town halls, and other forms of information sharing about the 2016 presidential candidates, both Democrat and Republican.

The results of a binding on-line CWA membership poll, released in early December, 2015, were not what Trumka predicted. Thanks to Cohen’s high-profile work as Sanders’ main emissary to the labor movement and voter turn-out efforts, within CWA, by L4B supporters and their locals, CWA did “go with Bernie.” As CWA spokesperson Candice Johnson told The Intercept. “Tens of thousands of members voted in the poll, with Sanders getting a decisive majority.”

Headaches for Hillary

By this point in 2015, ten other national unions had, via their usual top-down decision-making, endorsed Clinton as fast as they could. But, as a headline in Bloomberg News warned: “Labor for Bernie Means Headaches for Hillary,” that were just beginning. Contrary to Trumka’s forecast, Cohen worked successfully with several other former AFL-CIO executive council colleagues whose unions became Bernie backers—including Hanley at the ATU, RoseAnn DeMoro at National Nurses United (NNU), and Mark Dimondstein, who is still president of the American Postal Workers Union (APWU).

Before the 2016 primary season was over, the total membership of national unions in the Labor for Bernie camp reached one million (although only CWA backed him as a result of membership voting, as opposed to a leadership decision). L4B backers included both AFL-CIO affiliates and independents like the United Electrical Workers (UE) and International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU).

Plus, Sanders won the backing of more than 100 local unions around the country, including many affiliated with national unions backing Clinton. Vocal minorities raised hell in the building trades, SEIU, AFSCME, and both major teachers’ unions when their top officials ignored membership advocacy on Sanders’ behalf.

Through grassroots organizing and on-line signature gathering, funded with a budget of less than $5,000, L4Bdeveloped a mailing list of 50,000 activists. They pledged to work, within their own unions and communities, to help Sanders win Democratic primaries in their respective states. As Donald Trump emerged as the likely Republican presidential nominee, Sanders continued to argue that he, not Hillary Clinton, was the general election candidate best positioned to counter Trump’s appeal to working-class voters, disenchanted with business as usual.

During the June, 2016 Democratic primary in New York, while losing to Clinton there, Sanders even challenged Trump to a debate—an invitation the latter wisely declined—to prove this point. The national AFL-CIO did not officially endorse his opponent until that same month, long after the late February executive council meeting at which Trumka originally hoped to confirm the federation’s backing of Clinton.

Before she became the party’s nominee, with critical backing from un-elected Democratic National Convention “super-delegates,” union activists helped Sanders win primary elections in 23 states and amass 13 million votes overall. About 250 Labor for Bernie supporters won delegate slots at the DNC in August, 2016, where they continued to rally other Democrats against free trade and for Medicare for All.

A Hard Act to Follow?

After the fall general election campaign, Labor for Bernie co-founder Rand Wilson and former ILWU Organizing Director Peter Olney were optimistic that Sanders supporters would remain part of an on-going, cross-union formation. All that was needed, they argued, was “sufficient union resources to coordinate our work” and labor leadership willing to “form a coordinating body and staff to begin implementing a unifying program in selected campaigns at the state and national level.”

This “new force for a democratic economy would also tackle issues like climate change and “our permanent war economy and militarized foreign policy.”

Such ambitious post-election goals proved hard to achieve, despite the promising June, 2017 launch of Labor for Our Revolution., which tried to steer trade unionists toward the 300 local or state committees then rallying former Sanders supporters under the banner of Our Revolution (OR).

Six months before, a surprising number of recent Labor for Bernie veterans had already detached themselves from its national mailing list, after they received a general election appeal to elect Clinton. And, without the unifying focus of the 2016 Democratic presidential primaries, even pro-Bernie national unions “soon reverted to doing their own thing in politics,” Wilson recalls.

OR remains a key organizational advocate for Democratic Party rules reform, foe of big money in politics, and backer of progressive candidates, many of whom were inspired by Sanders’s first race. Chaired by Larry Cohen, OR aided Sanders’ second presidential campaign and continues to champion workers’ rights and grassroots opposition to the wide-ranging Republican attacks on democracy, unleashed after Jan. 20 of this year.

The difficulty of fostering a durable vehicle for independent political initiatives, rooted in unions, was the subject of a recent phone conversation with now retired California Nurses Association/NNU leader RoseAnn DeMoro, a key Labor for Bernie advocate in 2016. As DeMoro lamented, “The hold of the Democratic Party on organized labor is something to behold.” And the truth of that was definitely on display in 2019-20.

Labor for Bernie, 2020

Three years after the Electoral College put Trump, rather than Clinton, in the White House, the Democratic presidential primary field for 2020 looked, initially, nothing like the eventual two-person duel between Sanders and Clinton in 2016. Nearly 20 Democrats—including two of Trump’s fellow billionaires—competed to replace him.

This created far more difficult terrain for the second iteration of Labor for Bernie. Sanders now faced competition not just from a plethora of corporate Democrats but also from Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren, long identified with many progressive causes. As a result, recalls one Sanders advisor, his pandemic disrupted second run for the presidency “didn’t have the same magic” or single galvanizing primary opponent, with a questionable record of support for labor.

L4B was officially re-launched in May, 2019. With an eventual budget of $35,000, it was able to hire some full-time help, a departure from the all-volunteer effort three years before. Local committees became active again in LA, the Bay Area, Chicago, Detroit, New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and other cities. As in 2016, they circulated petitions seeking labor voter pledges to support Sanders in the primaries. They organized debate parties, spoke on Bernie’s behalf at local union meetings, and marched in Labor Day parades.

According to Paul Prescod, then a teacher’s union activist in Philly, L4B lobbied the local labor council to host a “Workers Presidential Summit,” featuring seven candidates, and then turned out supporters for the event. Hundreds of union members attended but, Prescod recalls, it ended up having “a sleepy feeling,” particularly when Joe Biden spoke. Bernie, per usual, got the most cheers—when he called for Medicare for All, the Green New Deal, and a Workplace Democracy Act.

In a crowded primary field, rank-and-file cheering did not translate into as much official labor backing as Bernie received four years before. In late September, 2019, Jonah Furman, the labor outreach coordinator for Sanders’ second campaign, reported that its only national union endorser so far was the UE. That smaller union was later joined by two larger organizational backers of Bernie in 2016– the APWU and NNU.

The latter, whose independent spending on Sanders behalf reached $1 million, according to one former staff member, devoted only a fraction of those resources the second time around. After a post-2016 change in presidents, neither the ILWU and ATU endorsed Sanders again.

Members Demand A Voice!

In a September, 2019, article for Labor Notes entitled “Members Demand a Voice in Their Unions’ Presidential Endorsements,” Furman reported that “several national unions had revised their presidential endorsement processes, in response to members’ dissatisfaction with the procedures used in 2016”—that were widely protested by labor backers of Bernie’s first campaign.

The largest union that backed Sanders first race—CWA—changed its endorsement process too, but not for the better. While Sanders was in the process of garnering 9.5 million votes and placing first in 8 primary elections, CWA headquarters officials refused to conduct another binding membership poll to determine its 2020 presidential endorsement, since that is not a requirement of the CWA constitution (or any other union’s).

Sanders contributed to this setback by informing CWA, via his 2020 presidential candidate questionnaire, that he favored anti-trust action in the telecom industry. In an accompanying message, Sanders called his otherwise very pro-labor positions “a snapshot of our great history together — and a glimpse of how promising and bold our future together will be, with your support.” When informed that anti-trust action harmful to several hundred thousand unionized workers and their customers would mainly be a boon for non-union competitors to AT&T and Verizon, Sanders stubbornly refused to withdraw his ill-advised campaign plank.

Then, in the Spring of 2020, Covid-19 made further in-person campaigning very difficult. As other candidates dropped out and threw their support to Biden, he became the last corporate Democrat standing between Bernie and the nomination. Faced with another convention delegate count deficit he could not overcome, Sanders withdrew from the race, at which point the CWA executive board backed Biden, as labor’s best bet for defeating Trump.

While the CWA national union reverted to form, 10,000-member UPTE-CWA, its largest west coast affiliate, ignored instructions from headquarters not to endorse a Democratic Primary candidate on its own. This active pro-Bernie local in 2016 put the choice of Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and the rest of the 2020 field before its own members. Sanders won again with 66 percent, with Warren coming in second with 22 percent of those voting.

Another 2016 Labor for Bernie backer was the California-based National Union of Healthcare Workers (NUHW). This statewide labor organization invited Sanders, Warren, Pete Buttigieg, and others in the field to address its 2019 stewards conference. NUHW then empowered members of that body, plus rank-and-filers voting on-line, to choose among them, based on their live video presentations and candidate questionnaire responses.

The result was a joint endorsement of Sanders and Warren, reflecting membership sentiment that was about evenly split. Sanders went on win the California primary in March, 2020 with help from these and other labor supporters more enthusiastic about his candidacy than the already failed one of their own U.S. Senator Kamala Harris.

Conclusion

Last year, there was another big blue-collar union, also with new leadership, that weighed in differently on the presidential election, but not by deepening its own recent process of internal democratization, The United Auto Workers entered 2024 with the great momentum of just having held a first-ever direct election of its own top officers. That resulted in leading members of the Unite All Workers for Democracy (UAWD) slate becoming an executive board majority.

It was no easy task for new UAW President Shawn Fain to rally members who felt cynical and disengaged because of the corruption and dysfunction of the prior leadership. Yet, during national contract talks two years ago, the UAW’s use of membership education and mobilization, unprecedented bargaining table transparency, and a selective strike strategy produced major auto industry gains, after years of divisive and demoralizing concessions.

A logical next step, in 2024, might have been changing the union’s approach to political action. If “one member/one vote” was a good way to get UAWD candidates elected and restore confidence in the union, why not also let the rank-and-file decide who the UAW should back for president, since that might add greater legitimacy to the union’s preferred candidate.

This was not the course taken by the new leadership. The UAW’s 400,000 members had the same limited and indirect voice last year that they had before UAWD’s victory. The question of who to endorse was decided by the union’s 15-member national executive board.

The much harder and politically riskier approach of empowering the membership gained popularity amid widespread enthusiasm for Sanders’ candidacies and L4B’s organizing around them. A decade later, using a more democratic method to endorse politicians is still the exception, not the rule.

That’s because a politically desirable outcome is not guaranteed, as demonstrated by the results of last year’s Teamster polling on Harris vs. Trump. Instead, it is dependent on internal political education and the degree to which rank-and-filers get out the vote for their favored candidate, which CWA supporters of Sanders did successfully ten years ago.

CWA’s own subsequent backtracking from giving members the final say in 2000 and 2024 would not have been possible if the union’s constitution required it to conduct a binding membership vote on presidential candidate endorsements. In the absence of such a mandate, more local unions can follow the best practices of UPTE-CWA or NUHW.

They should find ways to empower their members at the local or state level to vet candidates and choose among them—based on union-provided information and advice–but without always giving the officialdom the final say. Over time, this greater willingness to trust an informed and engaged rank-and-file, might even prove to be as contagious as “feeling the Bern” was in the heyday of Labor for Bernie.

…

The Pope

By Nicola Benvenuti

Pope Leo XIV (the former Cardinal Robert Francis Prevost), by his training and character, will—while keeping the content unchanged (the script is always the same, the Gospel)—certainly be more rigorous and attentive than the combative but somewhat instinctive Bergoglio (the late Pope Francis). I believe this trait, along with his background as a missionary amongst the poor in Peru, led the vast majority of the conclave to support the North American proposal. A too-striking shift—or confirmation—compared to Francis would have highlighted divisions and conflicts. Instead, it seems Prevost received the approval of over 100 cardinals, positioning himself as the guarantor of a new unity.

He won’t, therefore, be the anti-Trump—and Cardinal Dolan of NYC believes he even wants to build bridges with the Tycoon—but he certainly won’t allow himself to be used in Trump’s attempt to create a political-religious community that cuts across churches and evades their jurisdiction, even in matters of faith. On the contrary, I presume Leo XIV will work to show the clean and popular face of the Catholic Church in the U.S., after the divisions and scandals (especially around pedophilia), in an effort to regain the credibility lost to other churches and religious sects.

The composition of the conclave, as well as the dynamics of Leo XIV’s election, also marks the decline of the Italian Church, which started as the favorite with Parolin and Zuppi, in light of the growing awareness that the future of the Catholic Church is shifting toward Asia, Africa, and the Americas.

The man is relatively young and has many years of pontificate ahead of him to define his policy—there will be time to evaluate him. Regarding workers, Prevost took the name Leo XIII, the pope who in 1891, with Rerum Novarum, laid the foundations of the Church’s social doctrine to confront the spread of socialism. Perhaps it is no coincidence that—this time amid the deafening silence of the left even on this issue—he expressed concern about unemployment, and especially about the conditioning of consciences that artificial intelligence could lead to.

…

This post was originally in the Italian, below.

Prevost per sua formazione e carattere sarà, con contenuti immutati (il copione è sempre il solito, il Vangelo), certo più rigoroso e attento del combattivo ma un po’ istintivo Bergoglio e credo che questa caratteristica oltre al curriculum di missionario tra i poveri in Perù, abbia fatto convergere sulla proposta nordamericana la grande maggioranza del conclave. Un cambio di rotta, o una conferma, troppo eclatante rispetto a Bergoglio, avrebbe sancito divisioni e contrasti: sembra invece che Prevost abbia ricevuto il consenso di oltre 100 cardinali posizionandosi come il garante di una nuova unità.

Non sarà quindi l’anti-Trump – e il cardinale Nolan ritiene che i ponti voglia lanciarli anche verso il Tycoon: ma certo non si farà strumentalizzare nella operazione di Trump di creare una comunità politico-religiosa trasversale alle Chiese, sottraendosi alla loro giurisdizione anche in materia di fede: anzi, presumo che Prevost si impegnerà a mostrare il volto pulito e popolare della Chiesa cattolica in USA, dopo le divisioni e gli scandali (soprattutto per la pedofilia), per recuperare la credibilità perduta a favore di Chiese e sette religiose.

La composizione del conclave ma anche la dinamica della elezione di Prevost, segna anche il declino della Chiesa italiana, partita favorita nei pronostici con Parolin e Zuppi, a fronte della consapevolezza che il futuro della Chiesa Cattolica si sposta in Asia, in Africa e in America.

L’uomo è relativamente giovane e ha davanti a sé molti anni di pontificato per definire la sua politica, ci sarà tempo per valutarlo. Riguardo ai lavoratori Prevost ha preso il nome di Leone, il papa che nel 1891 con la Rerum Novarum pose le basi della dottrina sociale della chiesa per fronteggiare la diffusione del socialismo, e forse non è un caso che (stavolta nel silenzio assordante della sinistra anche su questo problema) abbia espresso preoccupazione per la disoccupazione, ma soprattutto per il condizionamento delle coscienze cui può condurre l’intelligenza artificiale.

Searching for Sinners

By Gary Phillips

In the classic ‘50s noir movie D.O.A., a shattered man who has been fatally poisoned walks into police headquarters to report a murder – his own. The tale of this dead man walking then unfolds via flashback. Also from the ‘50s was Invasion of the Body Snatchers. The story begins with a haunted-looking M.D. being held in an emergency room under psychiatric watch. He implores another doctor, “Tell these fools I’m not crazy.” Thereafter his tale of cold, calculating creatures possessing humans, hollowing them out, is told in flashback.

The recently released atmospheric vampire film Sinners by writer-director Ryan Coogler opens on scarred Preacher Boy Sammie. Driving a flivver, he too is haunted. He arrives at the country church presided over by his father, the right Reverend Jedidiah Moore. Limping, he enters the church, gripping the neck of his destroyed Dobro guitar as if it were a life preserver. Like in many a western, the double doors thrust wide open, Sammie remains backlit in the doorway. He’s unsure if he’s going to come in. His father implores him to do so. A riff on the notion the vampire won’t enter your abode unless invited.

Sammie enters. His father asks him to let go of the guitar. He knows his son is torn between the church, and playing the blues, the devil’s music.

For what does the blues offer but temptation. Songs about drinking, chasing wanton women (and men and women as sung by Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith), and gambling. There’s no better bad example Reverend Moore can point to here in Clarksdale, Mississippi than Delta Slim. The worn out alkie harmonica player who haunts the train station, playing his tunes for coins in a cup. Enough to buy a bit of food and refill his flask.

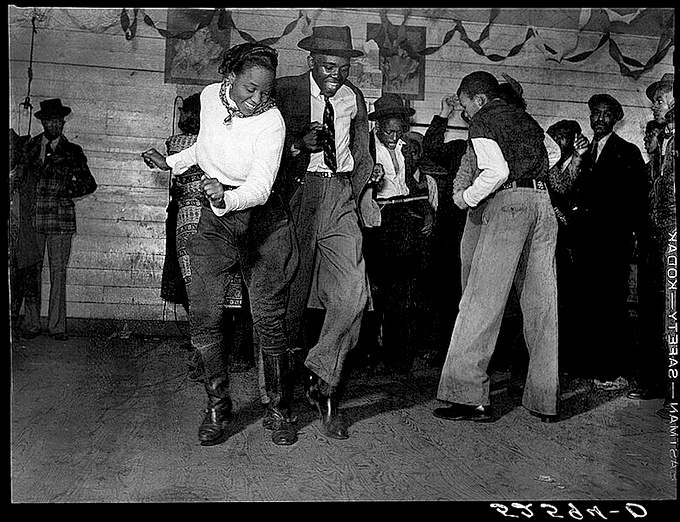

The depot Slim inhabits is where bluesmen such as Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and John Lee Hooker caught a train. They’d played the juke joints in and around Clarksdale. Firey Saturday nights where Black fieldhands and maids could laugh and drink and dance, if only for a few hours out of a week of backbreaking toil. Guitars in hand, those blues artists escaped lives of drudgery spent sharecropping. They sought something better. Seventy miles north they plied their trade in Memphis, and beyond to places like Chicago and Detroit.

Standing among the pews, Preacher Boy Sammie can’t let go of what remains of his guitar. The guitar he knows now didn’t belong to Charlie Patton. That doesn’t matter. It’s a powerful totem against the horrors he’s experienced — the dead walking, friends possessed. The flashback begins taking us to the day before. This was when Sammie’s twin first cousins returned. Elijah Moore, known as Smoke, and Elias Moore, known as Stack. The twins are tough WWI vets who worked for Al Capone’s outfit and have come back home to work for themselves. Smoke tells Sammie Chicago wasn’t much different than down here in Mississippi in terms of how Black folk are treated. “Better to deal with the devil you know,” he says.

The twins have purchased a former sawmill they plan to turn into a juke. It’s noted the floorboards have been scrubbed cleaned. The juke’s grand opening will be tonight. A reasonably sober Delta Slim along with Sammie Moore will provide the music. As observed by Samuel James in his April 24, 2025 post for his Banned Histories of Race in America, “A Quick Guide to the Blues in Sinners,” Delta Slim (played with his usual verve by Delroy Linbdo) is inspired by real life fabled Delta bluesman, Eddie James “Son” House, Jr.

Son House lived the life that is the backdrop to Sinners. He’d been a levee camp worker, a gandy dancer laying railroad track, a Baptist preacher who knew the sixty-six books of the Bible backwards and forward, a rivet heater, and a Pullman porter, He too wrestled with the bottle.

He entertained in those jukes in and around Clarksdale, sometimes playing those gigs with Willie Brown, or Robert Johnson, or the gravel-voiced, enigmatic Charlie Patton (Also spelled Charley). Clarksdale is where the crossroads of highways 61 and 49 meet. Where Robert Johnson was said to have come one high midnight to sell his soul to the devil so as to play the blues like no other.

Charlie Patton, who once survived getting his throat slashed, was known to drop to his knees when performing. He’d put the guitar behind his back and wail. A feat repeated by guitarist Jimi Hendrix decades later.

At one point in the early ‘40s Son House put the guitar down for some twenty years. In an interview with Studs Terkel on WFMT on April 19, 1965, he told Terkel the early deaths of Brown, Johnson and Patton haunted him. He’d get any kind of little twinge and he’d get worried. Maybe he might be next he opined. Best leave the blues be. Son House grappled with the blues over his lifetime. It was a music he’d been warned as a boy as Reverend Moore had warned Sammie, was the devil’s way to seduce you. Isn’t that why Remmick, the head vampire in Sinners comes to the twins’ juke? Through the piney woods he’s heard Sammie Moore’s guitar playing. He’s felt what his music can conjure, calling to the dead and the living.

When Sammie plays “I Lied to You” the spirits of the ancestors are invoked as are the representations of what’s to come. From griots and tribal dancers to hip-hop and electric funk, swirl about. There is so much energy from all this, figuratively the juke’s roof is on fire — as in the ‘80s rap “The Roof is On Fire” by Rock Master Scott and The Dynamic Three. In the battle with Remmick’s transformed flock, including the turned Stack and his girlfriend Mary, the jury-rigged juke will literally burn to the ground. Remmick is injured when Sammie smashes his guitar over his head, the resonator, the stylized metal covering over the sound hole, slicing into the vampire’s skull.

Daybreak and the surviving Smoke has unfinished earthly business. He sends Sammie away. He’s found out the man he bought the sawmill from, Hogwood, is a Klan Grand Wizard. The floor was scrubbed clean because Black men were beaten and lynched at the sawmill. The place was cursed. Now Hogwood and his fellow Kluxers are coming to get the drop of those uppity twins. Only in true gangster fashion Smoke uses a “Chicago typewriter” a drum-fed Tommy gun to mow them down. But he’s fatally wounded, having dispensed his brand of rough justice for the dead. He sees his deceased child with Annie, the woman he loves who begged him to kill her when she was bitten in the fight with the vampires.

Only Preacher Boy Sammie survived that God forsaken night. In the first of two after credit scenes, we see an aging scared Sammie Moore as embodied by blues great Buddy Guy. It’s after his set in a club in 1990s Chicago and Smoke and Mary walk in.

In an interview with Jeff Todd in Living Blues magazine issue #31, March-April 1977, Son House recounted. “I went on; I was there in that alfalfa field and I go down, pray, getting on my knees, in that alfalfa. Dew was falling. And man, I prayed and I prayed and I prayed…” Yet even sanctified and preaching, Son House eventually picked up the guitar and played those smoky jukes. For whispering to him as he told Studs Terkel, God was on one shoulder, the Devil on the other.

###

Gary Phillips first went to Clarksdale as a teenager. His mother’s side of the family was from next door Shelby. He went to the crossroads decades before a monument was erected there. His reissued novel Only the Wicked is set in the Delta of the 1990s.

…

Making American Banking Risky Again

By Rick Girling

Trump’s Gutting Financial Protections Placed after 2008 Financial Crisis

If you, like millions of others, are a victim of financial fraudsters, debt collectors, excessive banking fees, a false credit report, unscrupulous payday lenders, or check cashers you can file a complaint with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). Unfortunately, there is little chance that the problem will be resolved now that President Trump is attempting to reduce its staff from 1700 to 200 and has replaced Rohit Chopra, the head of the agency that saved and recovered at least $23 billion for consumers, with Trump loyalist Russel Vought.

In January virtually all of the agency’s workers were put on notice that they likely will lose their jobs. Hundreds of workers in San Francisco’s Western Regional Office received notices that they were on administrative leave and told not to return to work and to stop almost all of the projects they were working on. A furloughed employee has said there are plans to close the office entirely along with all the other regional offices except Atlanta. While their National Treasury Employees Union was granted a preliminary injunction to preserve the CFPB on March 28 by DC District Court Judge Amy Berman Jackson, the Trump Administration has appealed the ruling hoping to neuter the agency charged with “Rooting out unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts or practices by writing rules, supervising companies, and enforcing the law.”

Since 2012, consumers have been credited or saved more than $23 billion due to CFPB actions. The CFPB won a suit against Wells Fargo for $3.7 billion for decades of mismanagement of auto loans, mortgages, and deposit accounts harming more than 16 million Americans gaining them justice after suffering fraud. The CFPB recovered $363 million from lenders who scammed service members and veterans by violating the Military Lending Act. The CFPB instituted a rule limiting overdraft fees to $5 instead of the customary $20-35 that banks charge customers who have the least in their accounts, a projected savings of $5 billion to consumers. Unfortunately, Congressional Republicans killed this rule in April allowing banks to go back to charging whatever they want.

Organizations working to democratize finance such as the California Public Banking Alliance, the San Francisco Public Bank Coalition and Americans for Financial Reform strongly support the work of the CFPB. They are also strongly opposed to billionaire tech moguls and bankers attempts to defang these effective regulators and consumer advocates.

Elon Musk whose DOGE started the mass firings may fear the CFPB getting in the way of his desire “to transform X.com, his social media platform, into a virtual wallet where people can send money to one another” without regulatory restraints.

Hai Binh Nguyen, an enforcement attorney with the agency in San Francisco notes the agency was designed to take actions against businesses that employ unfair tactics, such as getting credit card companies to return money from disputed charges and stopping businesses like Wells Fargo that opened thousands unauthorized accounts.

The shuttering of the CFPB has met strong opposition from those that want to see American families protected from financial scams and mismanagement. Senator Elizabeth Warren posted on Twitter/X, “Understand this: by trying to kill the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Elon Musk and Russ Vought [the acting director of CFPB and key architect of Project 2025] are trying to make it easier for big banks to cheat you. It’s another way the Trump administration wants to reward the rich and powerful while hurting working people.”

Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison, tells the story of Sharon Tolbert-Glover who was swindled by mortgage refinance salespeople who claimed they could reduce her monthly mortgage payments. The contract these fraudsters sold her instead raised her mortgage payments from $1200 to $1900 a month leaving this ex-nun with only $200 left for necessities after receiving $2100 from social security and her deceased husband’s pension. This horror story led Ellison to become an outspoken defender of the CFPB.

With Trump’s attacks on the CFPB and his installation of banking and crypto friendly regulators, the chances for another financial collapse, as bad or worse than the one in 2008, are greatly increased. A key role of government is to protect the general public from unscrupulous actors that rob us; Trump and his billionaire backers would like nothing better than eliminating these protections in order to secure even more profits.

…

May 1st: We Will Not Stand By, We Will Not Allow This to Happen

By The Editors

May 1st 2025, the first Labor Day in the 2nd Trump presidency.

Marchers, supporters of labor, union members, defenders of human rights and the rule of law gathered and marched in cities around the country.

In Chicago, San Francisco, Solvang, Boston, Philadelphia, New Orleans people took to the streets to raise their voices in support of a greater United States, and against the proponents of inequality, greed and hate.

There were demonstrations all over Florida, Colorado, Connecticut, California, Georgia, and the Deep Red South.

If you have reports, one or two paragraphs, and/or 2-3 images send them to the Stansbury Forum

…

May Day 2025: The current installment of an annual remembrance (1)

By Robert J.S. Ross, PhD

Dear friends, comrades and colleagues

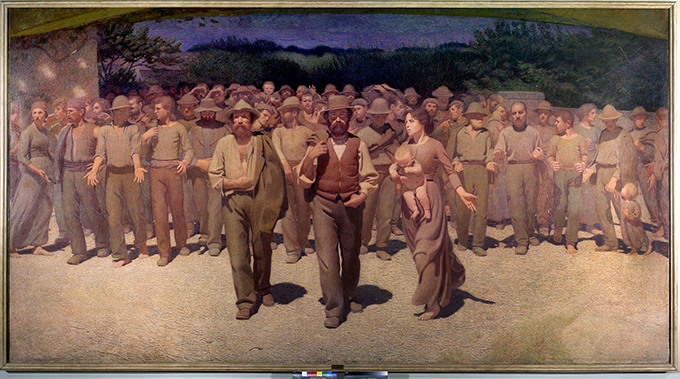

The story of May Day as an international worker’s holiday has its distant origin in Chicago in 1886. And it finds its relevance in the current Administration’s full throated attack on trade unions and standards of working conditions.

Since late in the eighteenth century American workers had sought to protect their lives and families –their humanity — by limiting the hours of the workday. As early as 1844 John Cluers led a labor federation calling for July 4 of that year to be declared a Second Independence Day in support of the ten-hour day.

Later, in the fall of 1885, the predecessor to the American Federation of Labor (AFL) decided upon May 1886 as the start of a series of strikes for the eight-hour day. They called for demonstrations declaring that after May 1 the working day would be de facto eight hours. Hundreds of thousands did demonstrate and strike that day, and tens of thousands won shorter hours.

The most memorable and tragic events of the 1886 struggle occurred in the days directly after what Samuel Gompers had also grandly called the Second Independence Day.

In Chicago, the May 1st rally in Chicago had been gigantic, and the city was tense. The Lumber Shovers union of 10,000 was on strike for the eight-hour day. They held a rally on May 3rd near the McCormick Harvester works, which was then gripped in a bitter lock-out and strike. As the workday ended at Harvester, strikebreakers came through the gates and some of the six thousand rallying workers protested against them. Police shot at the rallying lumber shovers and killed four on May 3rd.

On the next day, May 4, the leaders of the Chicago Eight-hour movement, anarcho-syndicalists of exceptional leadership ability, most of whom were immigrants, called for a protest of the shootings and a demonstration of resolve. It was rainy and there were numerous neighborhood rallies that day. The crowd was small. It dwindled from three thousand when the charismatic Albert Spies spoke, followed by his comrade Albert Parsons. By the time Samuel Fielden began his address the crowd had become only 300.

Then, 180 armed police, who had been waiting in a side street, marched into Haymarket Square, surrounded the small throng, and ordered the crowd to disperse. Fielden defended his right to speak. The police approached the platform and a bomb was thrown at them. One officer died there and six later. Later research showed that five of the six police who later died were shot by friendly fire as a result of police indiscriminately firing into the crowd. [Eighty-four years later, on May 4th, six Kent State University students protesting Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia, were shot and killed by National Guardsmen firing indiscriminately into a crowd of demonstrators.]

With scant evidence, the leaders of the eight-hour movement were tried and convicted of the murder of one of the police. Four were eventually hanged in November 1887; years later a courageous governor of Illinois, John Peter Altgeld pardoned three who were still in jail. One of the eight died in prison (a suicide).

After the convictions of the Haymarket leaders a worldwide movement in their defense spread through the labor and socialist camps. Thus, the American struggle for an eight-hour day was internationalized by the trial of the Haymarket martyrs.

The Haymarket bombing sparked the first Red Scare. Police around the country hounded labor leaders and socialist and anarchist groups. The defense efforts were not successful – although three of the eight eventually had their death sentences commuted and they were later pardoned.

However, by 1888, Gompers and the AFL were ready to launch once again a militant movement for the eight-hour day. The AFL called for a series of demonstrations, including Washington’s Birthday and July 4th 1889, and May 1, 1890.

“… it is a good time, as attacks on our rights and benefits mount, to celebrate and experience solidarity”

In the summer of 1889, the (Second) Socialist International was being re-founded in Paris. A representative from the AFL read a letter from Gompers to the Socialist Congress asking for support for worldwide demonstrations in favor of the eight-hour day. The French representative LaVigne inserted into a prior resolution on the eight hour day support for the American demonstrations on May 1st 1890. And so, around the world on May 1, 1890, workers called for the eight-hour workday – and many struck and achieved it or shorter hours. In Vienna, the entire working class called the day off. In the United States, the Carpenters, leaders in the struggle, won shorter hours for 75,000 workers. By the next year, 1891, it appeared that the May 1st demonstrations for a shorter workday had become an international and regular practice, becoming also a call for universal peace and a celebration of working class power.

Eventually, the conservative wing of the AFL would cause that labor federation to give up ownership of May Day and instead to preserve Labor Day in September as a more conventional American celebration. Around the world, though, both socialists and communists treat May Day as workers’ celebrations.

In the last few years the mainstream labor movement, i.e., the AFL-CIO, has come to acknowledge May 1 as “Workers Memorial Day.” And it is a good time, as attacks on our rights and benefits mount, to celebrate and experience solidarity.

The precious time workers wrenched from the grasp of employers and courts is embodied in our Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. It requires overtime pay past eight hours in a day or forty hours in a week, as well as giving Congress the authority to set a minimum wage. Its companion was the Wagner Act, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, committing the nation to support unions and the right to collective bargaining. Each of these is a pillar of decency and support for the dignity of work and labor; and each is now under attack.

There will be broadly based demonstrations on May 1, here in the USA defying Trump and his band of bumbling fascists, and elsewhere wherever working people are able.

I’ll be on Boston Common; perhaps we will greet each other there..

Solidarity

Bob Ross

1)Emended annually, the basic historic narrative is culled from May Day: A Short History of the International Workers’ Holiday, 1886-1986 Paperback – January 1, 1986 – by Philip Sheldon Foner

…

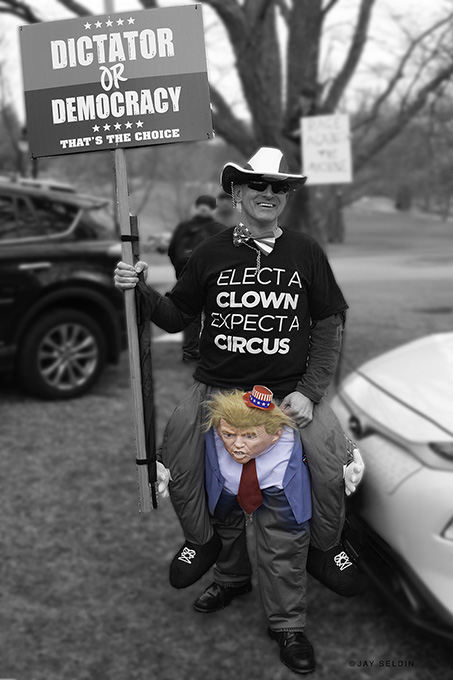

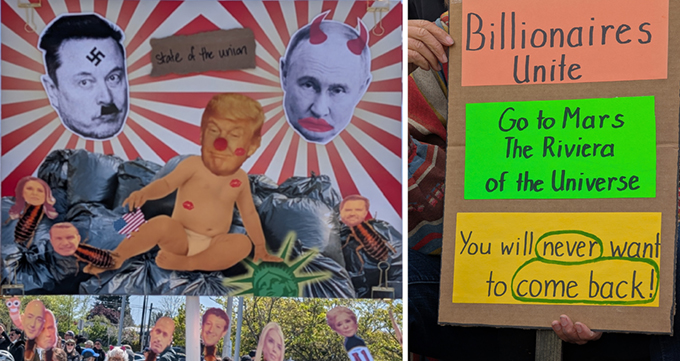

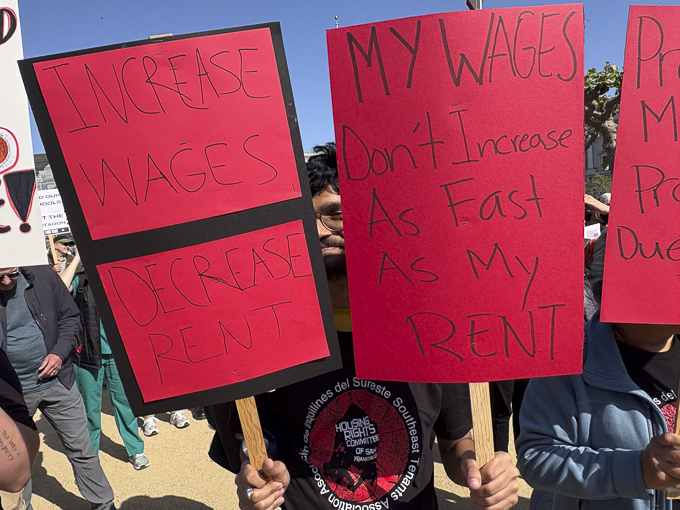

Photo Friday – April 25 2025

By The Editors

Protests at representatives’ offices, demonstrations and “empty chair” events are happening all over.

These are the beginnings of a community not willing to accept what is happening. Acknowledging that community the Stansbury Forum will post images of protest signs on Fridays to celebrate people’s creativity, and community. Today is the first “Photo Friday”. With your help, there will be many more.

Nationwide demonstrations are happening on May 1st – to find one near you try these sites: FifityFiftyOne; ActionNetwork

The Stansbury Forum would love to run images of these events on Photo Friday. Please send 1-5 of your favorites to: thestansforum@gmail.com

Include when and where the photos were taken and how you want to be credited.

Today we are running images from: Martinsburg and Charleston W.V; Santa Cruz, CA; San Jose, CA; Passaic, NJ; Montclair, NJ; Boston, Mass; Oakland, CA.; Berkeley, CA; San Francisco, CA.; Tucson, AZ.

…

Give Light, and the People Will Fight

By Jeff Crosby

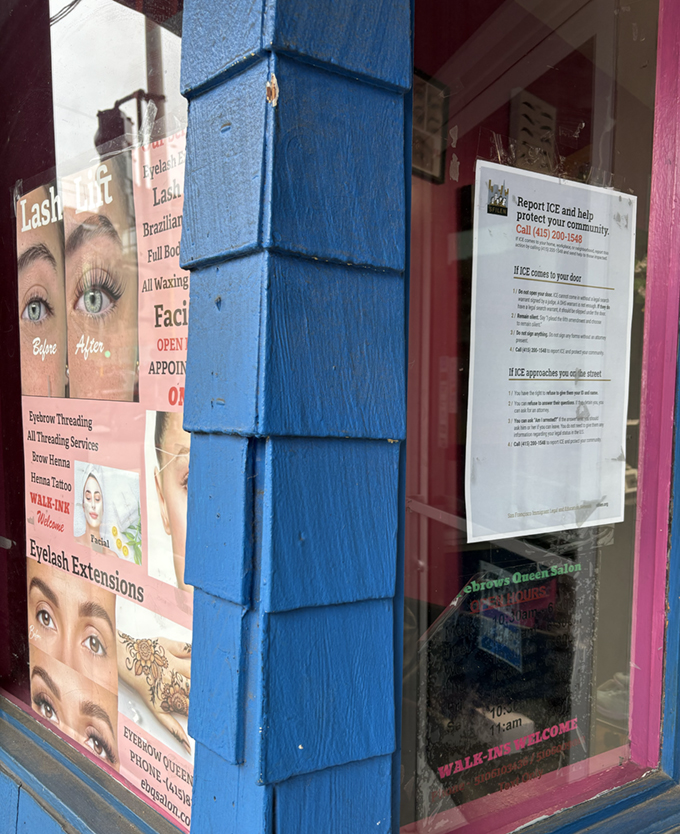

While the above illustrations are not specific to the following piece, they are recent examples of points raised below.

Rallying to defend our immigrant neighbors

In February 2025 in Lynn, Massachusetts, ICE grabbed an 18-year-old high school junior from Nicaragua and put her in a cell in Maine, hours away from her family. She had been involved in a minor argument with her 12-year-old brother over a cell phone and pushed him. A neighbor reported a “domestic dispute,” and the police came to the teen’s house and arrested her for assault. The DA dismissed the charges and referred her to counseling. But ICE grabbed her anyway, since she had initially crossed the border illegally—even though she had turned herself in with her family, was waiting for an asylum hearing, and had a legal work permit. It took a cohort of elected officials and pro bono attorneys to get her home after four days in jail.

The abuse got state and even national attention.

Members of the New Lynn Coalition reached out to New Lynn officers with a question: What can we do? And a request: do something! The coalition, a collection of quite different organizations of faith, labor, and community groups, has been together for 13 years, building relationships and working-class power in the city. We had also organized a successful response to Vice President Vance’s racist ramblings about Haitians stealing cats and dogs and eating your house pets a month earlier. This laid the groundwork for a quick and strong response when Trump won the election and began to implement his program of deporting millions of immigrant workers (or maybe just violent criminals, as he and his spokesmen sometimes promised).

Blocking ICE

Our immediate goal was to break through the fear and reassure our immigrant neighbors, with papers and without, that Lynn remains a welcoming city and there are broad forces in the community who have their back. Our migrant neighbors had in some cases pulled their children from school, and even stopped going out altogether. We also hoped to oppose the right-wing groups that were celebrating Trump’s moves and push ICE away from Lynn by encouraging everyone to resist it in any way possible. This can be seen as part of the “Block” part of the helpful paper Liberation Road published: “Block, Broaden, Build.”

Before the election, the challenge was to keep Trump and his New Confederacy forces from winning the vote. Now the task is to prevent Trump from consolidating power, which they did not achieve during the election but are hell bent on doing now. Trump won the popular vote by about 1.2%, but is acting like he won by 90%, which is part of his strategy.

The Coalition and new friends organized a protest at the courthouse and City Hall around the demands “Defend our Community! Defend Democracy! ICE Out of Lynn!” After our partners called on us to act, we facilitated two open planning meetings of 25-30 people on short notice. It would have been more efficient to simply call a board meeting of leaders who already had built trust with each other. But although the broader open meeting was more challenging to facilitate, it brought in new groups and individuals who deepened our understanding of the moment and what we had to do.

While we were doing our urgent planning, an undocumented Dominican was arrested and charged with a brutal murder in Lynn—a restaurant owner was tied up and killed in his own home. The right-wing picked up on this as they do, despite the multiple studies demonstrating that undocumented people commit less crime than those of us who were born in this country. Donald Trump Jr. tweeted about the murder, and Border Czar Tom Homan spread the word about the heinous crime and the accused. (By the way, when we finally build a stronger and deeper democratic country, can we finally get rid of this “Czar” thing?) It was all over local Fox News, and local and Boston papers covered the murder as well. Local internet warriors called for vengeance and blamed our Mayor for being too soft on immigrants: “He has blood on his hands!”

Tensions were high. The police called our Executive Director the day before the Tuesday rally and asked us to postpone it for two weeks, at least until after the funeral for the victim. This caused a serious discussion among New Lynn Coalition officers and the wider board and planners. People spoke about being fired on by the militaries in their home countries, and honestly worried about who would take care of their families if something happened to them. There have been Trump rallies and confrontations in the area in the past – we do have blue state fascists, like the eastern Massachusetts-based neo-Nazi group NSC-131. But the police reported no specific threats against us.

We were also concerned that if we went ahead as scheduled, and something bad did happen, the police could reasonably say they had asked us to postpone and we refused. We would take the blame for something that could potentially be tragic.

Nonetheless, we decided to go ahead. It was too late to cancel in any case — the upcoming protest was all over social media so some people would show up regardless, and it would be less safe if we were not there with marshals and larger numbers. A two-week delay would give the fascists more time to mobilize. And fundamentally if we shut down every time Donald Jr. tweeted, we might as well fold up and admit defeat. This is not going to get any easier any time soon.

The rally was successful. The police were out in full force and did a good job of protecting the rally. It felt like the entire city force was deployed, ready for Armageddon. Our main concern was crossing the street between the Courthouse and City Hall, where we might be vulnerable to a car ramming, but the police blocked off the entire two blocks and also the roads approaching the area, so it was safe. There were no incidents. A pro-Trump rally was supposed to take place on the following Monday, apparently in response to ours, and no one showed up. This is still our city.

About 250 to 300 people attended the rally. Speakers at the rally represented faith, labor, youth, and community organizations, and elected officials. A Guatemalan group that we had not worked with previously joined the planning and turnout. Four local Democratic town committees advertised the rally, although they don’t appear to have the muscle to drive turnout. The youth speakers, from El Salvador and Guatemala, were terrific. The elected officials were measured and careful, with several coming despite the warnings, including the mayor. The time of day and the cold and darkness meant a lot of union people and elders couldn’t come, but there was a good representation. Some people did not come out of fear, and some of our nonprofit advocates and adult education sympathizers didn’t show up, probably out of fear for their students, or fear of losing funding. There was a scattering of people from nearby towns. The rally got good press and was considered a success by everyone involved.

Broadening Resistance

As always, we tried to broaden the democratic front as much as possible. To prevent the consolidation of fascist New Confederate rule, we need all hands on deck, including people with whom we have many, and sometimes important, disagreements.

For example, evangelical clergy in the Guatemalan community stood with us at the rally, and both an evangelical and mainstream pastor spoke. These same evangelicals had opposed adding a demand for a ceasefire in Palestine for our annual May Day march last year, and discouraged their parishioners from attending. (“Evangelicals” is a term that covers a lot of ground, and they are not monolithic on this or other issues.) And before May Day the same people, with important influence in their community, had worked with us in the fight to allow undocumented workers to obtain drivers’ licenses. We respect and build relationships with them, even when we disagree.

Elected officials are another example. Prior to the earlier Haiti event, the entire City Council and Mayor signed a strong statement that we wrote, including “We welcome migrants and commit to using every available means to prevent the harassment and deportations of migrants and their families, including Haitians who have faced racist dehumanizing insults from high ranking government officials including President elect Trump and his VP JD Vance as well as openly fascist groups across the country.” The public statement the council adopted after Trump was elected was more cautious and legalistic, and city councilors were emphasizing that immigration was not a local issue. They were explicitly worried about losing federal funds for local projects, etc. In a post-industrial city like Lynn, which only recently started to see some investment after 40 years of neoliberal abandonment, that is not an unreasonable concern. But several councilors marched at the front with us. The mayor attended on his own, and we invited him to speak. While there are different opinions in our coalition on the mayor’s record, our base was glad to see him at the rally and it was comforting to many to hear him speak, and it was the right thing to do.

We specifically reached out to small businesspeople as well. The coalition’s mission is explicitly “to organize all sectors of working-class people in our region into a unified, permanent, political, and economic force.” In one election, one of our partners endorsed a Haitian small businesswoman who opposed raising the minimum wage, and of course the unions would have no part of that and opposed her. But we knew from experience that small businesspeople were likely to be on our side this time. They have deep ties to the immigrant communities who buy their products, with and without papers, including their own families. During immigration raids under the Obama administration, immigrant neighborhoods were shut down, and struggling local businesses suffered. One owner told me that his restaurant is once again suffering– partly because people are afraid to venture out, and also because people are saving money in case they have to pack up and head back to their home countries. So we successfully involved a small businessman to speak at the rally.

These elements of the community may not be with us on the next issue, but it was important to respectfully bring them into joint activity to protect immigrants and defend democracy, including those who have differed with us in the past and will differ with us in the future.

Mass Line, Give Light

Ella Baker, the brilliant veteran mentor of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee in the 1960s, told us, “Give light, and the People will find the way.” Her work has influenced me more than any other organizer/leader. Mao Tse-tung, leader of the Chinese Revolution, used the term “mass line,” or “from the people, to the people.” You start with the understanding that people make history, not brilliant organizers or leaders (you know, like me!). You respectfully listen to what people are saying and thinking, find the truth in it (because it is indeed there) and return it to them in a more thought-out form in a program that leads us forward, against the actual enemies that we face. Yeah, easier said than done!

We had a lot of conversations in a very short period of time about what we wanted to say, and did not always agree. But we did not have to agree on everything–it’s a coalition. For example, I had originally proposed to the planning group three slogans: “Defend Our City! Defend Our Country! ICE Out of Lynn!” The idea of the middle slogan was to tie us to the broader movement across the country—we are part of something bigger than ourselves. A Muslim woman objected that this sounded too much like Homeland Security calling for defense of the “motherland” against Muslims, invading children of immigrants, etc. She was right, and we switched to “Defend Democracy!!” at her suggestion. This was also at least a small empirical counterpoint to the argument that working class people don’t care about abstract things like “democracy.” In my experience they do, when it is represented in concrete form.

On the issue of crime, with the murder hanging over us, some people didn’t want to mention crime at all or the murder at all, concerned that it would become the main story in the press and keep us on the defensive the whole time. We decided there was no way to specifically address the murder effectively in the context of our march, but I did argue in my own speech that Trump lied about getting rid of violent criminals: “What does that have to do with snatching a high school junior from her home?” It seemed important to draw that line, since we had heard even from undocumented migrants that Trump was only going to go after criminals, not just anyone who arrived here without proper papers. Often these folks were fleeing violence themselves and were not any fonder of violent criminals than anyone else in this country. I think that was the right approach, but others were concerned that we not jump on the “law and order” bandwagon and support mass incarceration, etc.

Even the day and time of the rally was contested. Some people opposed a Saturday march since it is not as good a media day. I and others wanted Saturday so more employed people like union members and elders who don’t venture out after dark could attend. I still think that, but it turns out democracy doesn’t mean you always get what you want.

Building Organization

Early in this Trump administration I read endless statements from Washington liberal pundits about the lack of protest: “Where is the resistance?” etc. In some cases they bemoaned working class support for Trump, usually overstating it, since they tend to look down their noses at working-class people anyway.

They were looking in the wrong places.

The response to our call for action against mass deportations under dire circumstances indicates that when given a clear opportunity from trusted leaders with a working class perspective and base, people will respond.

More important in the long run, people are building organizations, not just protesting and marching in random ways, although there is plenty of the latter as well. And that’s a good thing!

On the North Shore of Boston where Lynn sits, there is more organizational growth than I can keep up with. Attendance at the labor council has increased. Our council president calls it the “Trump Bump.” The organization Indivisible held an initial reorganizing meeting of 20 people—the next month, they had 100. The Democratic Socialists of America is building a renewed chapter. A coordinator of a new local group Solidarity Rising told me she went to sleep a few nights after the election and 10 new people had signed up for their newsletter when she got up the next morning. The League of Women Voters has organized multiple protests. Undocumented workers themselves organized their own protests before New Lynn could organize one, despite the fear that many people (including me) had of possible attacks from ICE. And it goes on.

After the rally we took a breath, but before long our partners were pointing out that we had no plan beyond the demonstration. One group suggested circulating Know Your Rights cards. Four partners contributed funds and we are printing thousands to be distributed in multiple languages in barber shops, nonprofits, tiendas, etc. For my part I had underestimated the “block” potential of legal resistance, but we saw in places like Chicago that aggressively exercising your rights can stymie ICE.

Another partner is putting together a state-wide hotline in coalition with other immigrant groups, to squash rumors, warn communities, and directly question ICE officers. Sometimes this causes them to leave. We are working on a message for a meeting with our congressman. There is plenty to do, and not enough time and resources to do it.

Most of all, “build” means build organizations of all kinds, from unions to community groups to youth organizing to faith communities to socialist organizations who have a strategic vision and plan beyond only playing defense.

Victory is by no means assured. But give light, and people will fight.

…

Originally posted on Liberation Road